ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Heathrow airport, London. February, 1970. A plane lands after a very long flight from Colombo, Sri Lanka. It’s a Vickers VC10 emblazoned with a logo that no longer exists, and the plane takes 151 passengers. The ground crew roll in the stairs, and eventually after a long wait the door opens, and people start filing out.

A young woman not yet in her thirties takes her time to make sure her things are together. She convinces herself that it’s to make sure she’s not forgotten any of her hand luggage. The truth is that she’s not got any hand luggage, and she’s scared of leaving the cabin. Finally she walks through the door, propelled by the smiles of the three air stewardesses. The first thing that hits her face is the cold. Then it’s a snowflake. Then it’s the tears. What have I done? She’s heard of snow before but has never seen it. What am I doing?

Hey. It’s Rohan, your host of Meditative Story, and I’m pleased to invite you into another one of my solo episodes. And this week I’m not sharing a story of my life. Actually it is very much a story of my life. But it’s probably fairer to say that it’s really my mother’s.

I think about those tears of my mother’s a lot – probably a couple of times a week if I’m honest. The salt mixing with the snow on her face. The coldness of the air. The grayness all around her in her vision, tarmac, terminal, sky.

Feel the touch of the world on your face. Any heat, any cool. Any energy.

My mother grew up in rural Sri Lanka, in the spaces where the wildness of the calle – or jungle – transitioned into the city. The oldest of four children and the only girl, she was the child of two head teachers, both rather strict. There is space to roam, and monkeys and birds and insects: an all-hours constant soundtrack. There are fights over who will get to suck the mango seed, after the fruits from the big tree out front are cut and shared. All water is got from the well, and it tastes so bright, cooled in terracotta jugs.

I get a taste of this too when I visit her mother, my grandmother, in the eighties and early nineties. I bathe outside by the well, the subterranean water just what I need in the humid 90 degree heat. I’m warned not to get too close to the monitor lizards. Growing up in London you get told not to go too close to swans since they will certainly – and entirely apocryphally – break your arm. In Sri Lanka, it’s monitor lizards. I think of my own children’s life today and how different it is to hers in Battaramulla and then Piliyandala.

When my mother first leaves home it is for university. Peradeniya University is on the outskirts of Kandy, the ancient hill country seat of kings. There are bougainvilleas everywhere. It sits in the embrace of the great Mahaweli river, and the nature is so beautiful. There is a royal botanical garden next door, and it’s hard to say where the boundary is. My mother is a great student, a nerd really, and goes on to be a lecturer in geography. It’s not hard to see why with the inspiration in the land all around her.

Is there somewhere you can time travel to? Place yourself in a moment in your own history, and imagine what it’s like to really be there.

When my mother next leaves home it is for England. Leaving the country and the family and the security she is so attached to. At the time, there are many stories told of the promise of moving to the UK. It’s an adventure, yes, but she doesn’t know what kind yet. She will marry a man who she’s only met a couple of times, my to-be-father driven to her family house in a 1950 Volkswagen Bug, bottle green. I visit the car every time I go to Sri Lanka. It’s in my uncle’s garage, and it is a pilgrimage. They marry later that year at the Commonwealth Institute in Kensington. That building doesn’t exist any more.

I live on the other side of the country from my mother now, me in Scotland, her still in the London suburb where I grew up. She often asks me when I’m going to move closer to her. When I ask her why she moved, she says it was for us. So that three unborn children, beings that did not exist at the time the decision was made, had a better opportunity in life.

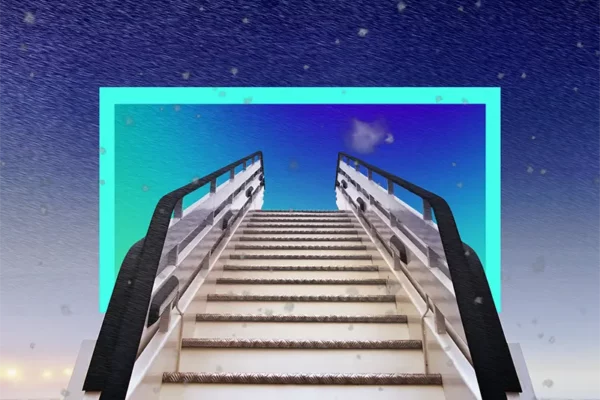

I think about this all the time. The tears on the runway. Her seeing snow for the first time, and the shock of that overwhelming her in an already overwhelming moment. She did it for us, she did it for me. Even though there was no me. I think about this more often than I bother to call her. But there is a threshold I walk up to in my thoughts, one that if I go beyond it, it becomes too much, and I’m there too. Top of the steps.

My mother used to think meditation was a waste of time. Then she saw how I was becoming a better Rohan. Then she learnt more about contemplative practice in general. If you asked her to describe meditation, she’d say it was about focussing on your breath. I’ve tried to explain a different more generous perspective of what it’s about, but she thinks what she thinks. So for her let’s just do that. Focus on your breath. Focus is a word that can have a lot of tightness built into it, so watch out for that.

Focus on your breath, but more importantly, be open to learning something about what happens when you do.

Doing the work. Walking down the steps. And doing it so that those that come after you have a better life.

Everything we do now affects everyone around us in the future. Even the people we’ve not met yet. What would it be to meet life with that sense of stewardship and care?

Thanks Amma.

I still can’t believe you did it, and I don’t know if I could do it myself.

And thank you. Till the next time.