To walk the Earth

In the morning, Idaho pastor Tri Robinson herds cattle and mends fences; in the evening, he writes sermons. But the two parts of his life don’t feel connected. He feels such a deep love of the natural world, in all its beauty, all its fragility. But what is he doing, as a leader, to help preserve that precious creation? As he carries that question with him on his daily rides, he realizes: he’s about to make a monumental decision. To change the way he walks in his faith – and walks on the Earth.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

To walk the Earth

TRI ROBINSON: Early every morning, I sit by the fire silently and drink my coffee. Sometimes I sit in silence for an hour. Then I saddle my horse, Dusty. He is a buckskin gelding. We head out into the morning light, and we work the fences, or pretend to.

What I am really doing is thinking and writing, in my head. It’s early spring. The red-wing blackbirds have just arrived for the season. The barn swallows are coming in droves.

I realize that my whole life I have been thinking about this very issue Kate raises. And I am in conflict. I come to the conviction that I can’t be silent anymore. I am writing the sermon in my head. The words won’t stop.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: In 1974, Tri Robinson and his seventh grade American Literature students persuaded the U.S. Congress to permit them to move the body of a famous mountain man from a gravesite alongside a Los Angeles freeway to his rightful resting place in the Rocky Mountains. It’s quite a story, and if you’re interested, it inspired Robert Redford’s film Jeremiah Johnston.

Later in 1980, while working among the Karen Hill Tribe people on the border of Myanmar and Thailand, a life-turning event convinced Tri to leave public education and enter full-time ministry.

And for 23 years, he presided as pastor of the Vineyard Christian Fellowship in Boise, Idaho. There, Tri has come to create one of the most progressive evangelical movements around today – a green movement to take care of lands, waters, and sky.

In today’s Meditative Story, Tri helps us see how our greatest accomplishments often begin when those we love challenge us. And when that happens, if we’re lucky, we let go of what we think we know, and emerge with new ideas that set us on the path of our truer life mission. It’s a lovely Meditative Story we have for you today.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

ROBINSON: The house smells like Nancy’s roast chicken and fresh herbs. Even though our two kids are old enough to live on their own, we still gather for family meals.

Kate is experimenting with salads: garlic and lemon dressing, toasted nuts. She’s given her mother an ivory lace tablecloth from her travels abroad, and it lays out like a flowing dress across the oval table.

The late summer sun shines through the curtains, which gently bellow in unison with the breeze. The scents from the flower beds outside invite themselves into our home. Idaho has a short growing season, and this is its finest moment. A dog barks down the street as I bless the meal.

We don’t usually talk about politics at the table. As an evangelical pastor, I’m not shy about where I stand, but supper should be a peaceful meal. I know the kids are wrestling with their views, becoming their own people, and I respect that. At 22, Kate doesn’t come to church so often any more.

It’s Brooke who starts it. “I honestly don’t know who to vote for,” he says. Al Gore, George W. Bush, Ralph Nader. The election is just a few months away. We get into it, and before you know it, Nancy has served some after-supper tea, and we’re still going strong. Kate is the one who voices the clearest thoughts. I study her, her long hair, framing her strong voice.

“Why is it that we’ve never heard a message from the pulpit on the environment, when it’s all over the Bible?” she says.

I find myself listening to her words as if hearing her for the first time.

I am proud of her passion, but I am also, in this moment, feeling shame for myself and my church and the Evangelical Christianity I have given my life to.

When I am 16 years old, my parents give me a 1956 Volkswagen Bug. I think the reason they give it to me is because it has zero power, but it gets me around. As soon as I take possession, I drive it two hours up to my family’s old homestead cabin at the edge of California’s Antelope Valley. It’s in a hilly wing of the Mojave Desert that looks across into the Sierra Nevada. It is the first time in my life I’ve ever been all alone in solitude. And I realize very quickly, I don’t quite know what to do with myself. So I walk up on this pine knoll. The sun is just setting. I understand I am here, because I am asking some uncomfortable questions.

I sit on the hill in the slanting light, looking out across the vast, massive desert into the Sierras. I smell the sap from the pine trees, and I smell the earth. I watch swift shadows of clouds cut across the silver valley.

In an instant, on this hill, it hits me that there is actually meaning and purpose in my life. That life is not an accident. I ask myself, “If this beauty means God is real, and if this is all not an accident, then I’m not an accident either.”

After college in the ’70s, Nancy and I move to that cabin. We raise our kids there, and I work as a biology teacher. We drink spring-fed water. We horseback into the Sierra wilderness, and the kids help build trails. Years pass, and again I question my faith. I tell Nancy I am going for a walk, and I go back to the very same knoll I came to when I was 16. There is a log.

I sit on the log, and I gaze at the grass growing and the wild flowers. I say, “Lord, I just need to know.”

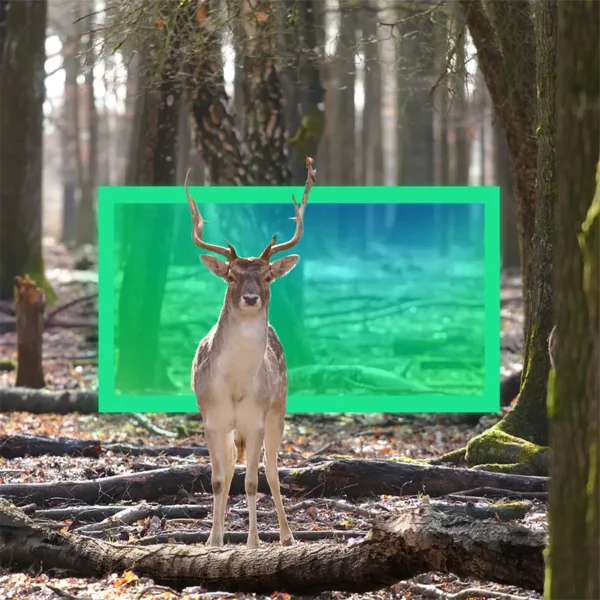

All of a sudden, I hear footsteps behind me. I am terrified because I don’t know what is coming. And I just freeze, I don’t even turn around. And this deer steps over the log to my left, turns around, and looks right in my eyes. And I have no questions after that.

GUNATILLAKE: Let’s sit with Tri here. Feel the temperature of the air on our face. The connection with our feet on the earth. Trusting in breath. Faith in breath. Out following in. In following out.

ROBINSON: We move to a ranch north of Boise, where we start a new church that ministers to the poor. We call it The Vineyard. I think of everything I do as planting seeds in the soil. I move cattle and mend fences in the morning, and work on church business and write sermons in the afternoon.

After college, Kate works for an environmental organization, and Brooke works for REI. It’s no surprise my kids are drawn to the outdoors because of how we raise them. It’s ironic, but I’m the one who ends up keeping my work – the work I love, pastoring and ministering and serving my community – separate from my love for the natural world. But it doesn’t sit right with me. This separation between my spiritual beliefs and the spirit of my everyday connection with the land, and its life sustaining abundance, it shouldn’t be this way.

By the time we are eating Nancy’s roast chicken, this divide has been eating at me for some time. The way my kids talk at the table. The way Kate reaches her hands out across the lace tablecloth, her eyes on fire, it makes me stop. It makes me question my silence on the environment at the pulpit. Kate and Brooke’s words profoundly challenge me. I find myself as a pastor, in my heart loving creation and in my heart loving God, but not being able to connect the dots publicly.

For six months through the long winter, I re-read the Bible. Now, I know and admire that so many of us on this blue planet find our spiritual source in different places. We all come to discover our higher selves in our own ways. I sit in my old leather chair by the wood stove in the living room. I read it all the way through, but this time with a green felt tip liner, highlighting everywhere I see something about the Creation or the environment. And the Bible becomes green.

I can’t believe how much is in there if you are actually looking for it. It just shocks me. Somewhere along the line, evangelical churches in America gave up on caring about the environment, because that was something liberals did. If I preach about it, I know there might be a lot of pushback, especially in Idaho, because people think environmentalists are trying to stop everything in terms of their livelihoods and so on. I’m just not sure what to do.

Early every morning, I sit by the fire silently and drink my coffee. Sometimes I sit in silence for an hour. Then I saddle my horse, Dusty. He is a buckskin gelding. We head out into the morning light, and we work the fences, or pretend to. What I am really doing is thinking, and writing in my head. It’s early spring. The red-wing blackbirds have just arrived for the season. The barn swallows are coming in droves.

I realize that my whole life I have been thinking about this very issue Kate raises. And I am in conflict.

I come to the conviction that I can’t be silent anymore. I am writing the sermon in my head. The words won’t stop. When I know I am going to say it out loud, I seek help. I know I have to do it right. Devotion demands action. I want this message to be a major call to action. I want our church to be a flagship for this.

I form a secret committee. I discover I have closet environmentalists all over the church. I recruit a forester, a parks specialist, a weed expert, a politician. I put Kate and Brooke on that committee too. Kate wears her Birkenstocks and drives to the meeting in her 25-year-old Volvo with the tree hugger bumper stickers. She is 22 years old, and I know she is nervous, but she comes. The only seat open at the long conference table is next to the politician, a big guy in a polo shirt and penny loafers. They eye each other.

“I know your politics, and I’m not voting for you,” Kate says. He laughs, and they both smile. We all talk late past the meeting time. And again, the next week. We make a plan: We will build trails, we will clean the Boise River, we will pioneer the use of cloth bags in the new millennium to reduce plastic, we will buy an old truck to handle recycling. I begin to think of Christianity as a verb, that it has to show action as a state of being, and I have a team of 2,500 parishioners.

GUNATILLAKE: Wherever you are, can you imagine 2,500 people around you now? All facing the same way, a force for good. That is a lot of people, a lot of hearts. And as you listen to this, there are actually many more even than that. This community.

ROBINSON: On the day of the sermon, I get up early in the dark, and I feed the animals. Then I change into my preacher clothes: a pressed shirt, Wranglers, and cowboy boots, my lucky belt buckle showing a man on a horse, pulling a pack train. Nancy and I drive the Subaru an hour down the steep mountain road to town. The snow is still melting, but the air smells like spring. I’m silent in the car.

I have two conflicting emotions stirring within me: fear and excitement. I have preached many messages on controversial topics, but never one that could be so potentially polarizing to the congregation or detrimental to my position in ministry.

But more than anything, today is about doing the right thing at the right time for both my church and my community. I have to shed my inhibitions. How will the congregation respond? There is only one way to find out.

Walking into the church foyer, I notice the subtle smells of coffee. People are sitting and chatting before the service. Soft light fills the room from the large stained glass window between the two entrances. I continue to the backstage, to breathe and quiet myself.

After a bit, the band starts, indicating it is time for the people to find their seats. It’s a charismatic church, so we have a vocalist, a couple of guitars, a drum, a keyboard, and a violin.

Then the room falls silent. I hear the clip of my boots on the floor as I walk out. I see the expectant faces of about 700 of them at this sitting. My kids don’t usually sit up front, but today, I see Brooke, then I see Kate holding a soy latte, sitting with Nancy.

I start with a prayer, and then I speak of my journey to this moment. I talk about the mountain knoll, and the deer, and the passages I keep finding in scripture. I don’t feel like I’m very eloquent, but I know I’m speaking from my heart, and the audience seems to be listening.

I watch the clock and measure how my time is going compared to the information I still want to deliver and the finale I want to hit at the end to challenge them to join me in a pro-environment stance and action plan for our state, and our city, and our neighborhoods.

And when that moment arrives, I see someone stand up and start clapping, then a dozen more and a dozen more until everyone that I can see in the room is standing and just clapping. And I see at that moment that I have just delivered a message they’ve been longing to hear.

I see tears in their eyes. I feel my emotions building. This doesn’t happen to me often in church, and neither does a standing ovation. I’m relieved. I’m in awe. My tears just come up.

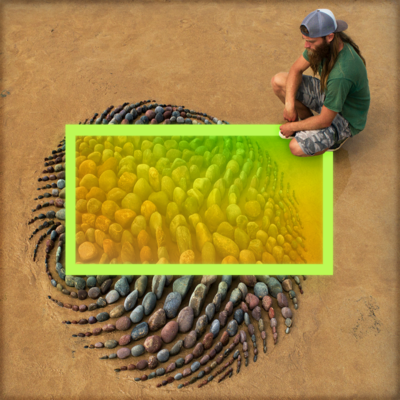

The momentum from that morning continues. The message just carries on. We make a mural in the main hall of the church. It’s got white walls like an art gallery, and we show large photographs of all these families in the wilderness. We break into teams, and we have jobs for everybody. They are excited – not just because I have made it okay to be a Christian environmentalist, because they get to play.

People from the community hear about our new work, and our church grows.

Twenty years later, I’m still the guy that’s known for this, and I don’t know why, because I know there’s many others now that are carrying the torch, but not as many as you’d think.

I’m retired from the pulpit now, but not from my work on the land.

I just got a new horse this week. I’ve always had horses, but this one feels different. I know this is my last horse this side of heaven. I’m 73, and my horse is a three year-old, so I’ve got a lot of time yet.

The hills are full of game, wild game. Saw a fox catching a ground squirrel yesterday. I keep an eye on the cows. We used to have Angus, but now we have a breed called Belted Galloway. They’re from the Scottish Highlands. They’re really hardy. They have a stripe around their belly. I don’t know if you’ve ever seen them. They’re quite beautiful, actually. I’m finding they’re really naughty, too. They like to go through my fences.

Sometimes I fix the fences right away, and sometimes, I just sit on my horse, and I look at those fences and laugh. My eyes look past the dangling wire down the valley, to where the hills meet the creek. I look past that to the horizon, where the sky meets the land, the land that belongs to all of us, and I feel the full force of Creation.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Tri.

Today’s story made me reflect on how we can all get so caught up in our own stories that we don’t see the bigger picture.

And so the meditation we’ll close with together is about seeing the bigger picture, or more accurately about seeing nature.

So let’s settle in. Doing what you need to do. Softening. Opening. Being here. Here in the space where you are.

There can be a tendency to divide the world into that which is natural and that which is not. As if they were different. But when we take some care and start to see nature in the environment around us, it opens us up to a sense of things that is slower and longer and more connected.

So let’s start by connecting, feeling our contact with the earth. Dropping as much of our awareness as we can into our feet where they touch the ground.

Gravity. Force. Our bodies, held up by the whole planet. Our literal connection with earth.

Now, where can we notice nature where we are? A plant in our visual field, if eyes open. The sound of a bird. If you can see the sky, the sky.

Allowing nature to be our experience. Direct, outside to inside via our attention and our care. The temperature of the air on our skin. Even just the sense of space around us.

Sound, sight, touch, heat. Whatever it is, however subtle. Knowing it. Knowing nature. Marking it with the green marker of our mind.

Now something different. Bringing to mind an image of the environment that is meaningful to you. A place you’ve been. A place you love. Or just a thing you love – a rainforest, a mountain, a creature, whatever.

Connecting with nature this way, through thought and image. Letting our love and appreciation and care soak into this idea of nature.

Letting it fill us up. Holding it in our heart.

May all creatures be well. May all trees and plants and grasses and rivers and rocks be well. May they be protected.

May all beings be well. May all mountains and oceans and deserts and forests be well. May they be protected.

May all beings be well. May all breathers and thinkers and bodies and sensing beings be well. May we be protected.

May we have the wisdom to know how we are separate from nature. And how we are not.

May we have the wisdom to see nature, to know nature in everything. And love it like nothing else.

Thank you again Tri, and thank you.

Stay safe and well.