Starting the story of my life again

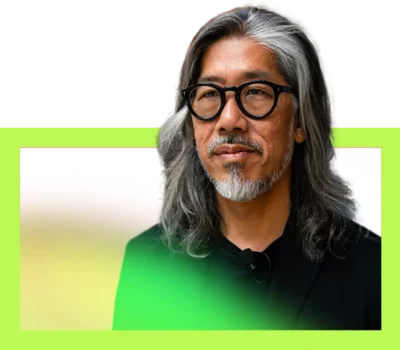

Fluent in cheating time to squeeze productivity out of every minute, entrepreneur Keith Yamashita recounts the frightening details of a devastating stroke as it is actually happening, and discovers the second part of his life. It isn’t a medical recovery. It’s an awakening.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Starting the story of my life again

KEITH YAMASHITA: Over the decades of my career, I have become fluent in this way of living: Cheating time. Compressing two tasks into one motion. Squeezing the most out of every single moment by not really ever being present in any of them.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Life does have a tendency to hit us when we are least suspecting it. Often it’s our bodies, perfect in their frailty. They give way and fail, reminding us that we’re perhaps not quite as invincible as we think we are.

That happened to Keith Yamashita, today’s storyteller. Keith started his career as a writer for Steve Jobs, and spent the last two decades working alongside visionary leaders and their organizations, from Oprah Winfrey to Howard Schultz to His Holiness, the Dalai Lama. In his work, Keith is a builder of brilliant things. But the story he shares today is about something starting to crumble. And what was revealed as a result.

In this series, we blend immersive, first-person stories with mindfulness prompts to help you restore yourself at any time of the day. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide on this episode of Meditative Story. From time to time, we’ll pause the story ever so briefly for me to come in with guidance to enhance your experience as you listen.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

YAMASHITA: Where does my story start? It could start right here, in a car dealership. On this very first day of living back in California. On this first day of me trying to redeem myself as a father. I’m here buying a car, because, well, you can’t really do much of anything with kids in California without a car.

I say to the first sales guy I see, “I have one hour. No more.” He gets up from his desk. I continue: “I know exactly what I want. I refuse to haggle. And I gotta make this quick, because I gotta get on a conference call.”

He looks down at me through his bi-focal glasses. To him, I am just “that guy.”

We walk through rows and rows of cars. True to my word, within minutes, I pinpoint the SUV I want. I offer the dollar-perfect price that I know hits his margin. And then, true to his word, he shows me a place where I can do my video-conference.

You see, over the decades of my career, I have become fluent in this way of living: Cheating time. Compressing two tasks into one motion. Squeezing the most out of every single moment by not really ever being present in any of them.

I gotta get on that video call. I situate myself: laptop open, headphones on. I take a swig of water. It trickles out of the side of my mouth. Odd.

The meeting is now in full force. I take another swig of water. This time, the water escapes my lips, down my chin. And I feel the cold trickle as it makes it way down my t-shirt. Maybe I’m just not paying attention.

So I turn off my laptop cam and mute my line. And I call my husband, Todd. He’s in New York, the city I lived in until just yesterday. I share the scenario: car, water, face, video conference, drooling. Drooling. Todd is hyper-logical and says, “That’s something you want to get checked out.”

I tell the sales guy I gotta cut the hour short. I hastily sign the papers for my new car. I ask for the keys. And so there I am, driving my new car.

I am having a stroke, but I don’t know it yet.

As my brain starts to dull, I try to make my journey to the local research hospital, but my path is hobbled by dozens of one-way streets all going the wrong way.

Or I could also start my story here.

I have no idea where my kids are. They are wandering somewhere, unattended, and completely innocent of where I am. I am flat on my back, on a gurney, being catapulted down the hallway. One. Two. Three. Four, I count. There are at least 12 people above me – doctors, nurses, attendings. The lead resident is asking me questions about the last several hours.

“So you can’t feel your face. What happened before that?”

They are now poking. Prodding. Taking vital signs. My inner voice is narrating the whole experience in my mind. We turn the corner. A door opens. And head first, I go into the MRI machine. It’s loud. Some people feel claustrophobic in here. But for me, it’s the opposite. I am calm. Almost soothed.

I come out of the MRI, I look up at the ceiling. Slow tears drip from my eyes down over my temples. The tears pool in my ears. I’m crying for my kids, who may not see me again. I have clearly messed up. I am not going to get that chance to redeem myself as a father.

GUNATILLAKE: Can you be with Keith here in this room, so stark, the loud hums of the machine as it moves him out of the scanner? Can you be with Keith in his emotions? So real, so direct.

YAMASHITA: Or my story could start here, in the aftermath.

Maybe this happened to me because I constantly chose the cause over me. The board meeting over helping the kids with homework. The finishing of the last email over being there at the start of dinner.Maybe this happened to me because I’m a great entrepreneur – but a bad dad. Maybe this happened to me because in trying to prove to you that I’m for your cause, I exhaust myself in the process.

I wake up in the hospital, and I know I need to assess the damage. But I’m scared. I know the right side of my face is dead. My speech is slurred. My cognition is blurry. Not ready for a full-blown mirror, I decide to cheat it: Selfie mode. I lift up my iPhone to catch a glimpse. But my face, in its mangled state, no longer serves as the passcode. Facial recognition fails. You know things are really bad when your iPhone gives up on you.

So I manually punch in the keyboard and, my lord, my face! Not a single movement to the right side of the meridian that divides it. I cannot make a single cell move. I send commands to my right eye lid, I cannot induce a blink. I try to move my eyebrow, nothing. My nostril: dead. My cheek: immobile.

I put the phone down. And I sit for two or three hours. Not moving. Not mourning. Not thinking. Not crying.

It’s then that the all-powerful head of neurology tells me, “We think you suffered a stroke in the base of your brain. There’s no guarantee that you won’t have a second one. And second strokes at the base of the brain are far worse than the first. And third strokes there are almost always fatal.”

It’s in that moment that I realize that recovery is going to be hard. And my only hope is to prevent a second stroke.

I think, really, my story starts a month later. I ask my doctor, “How long will I be out of work?” “If you are lucky, maybe six months. More likely a year.”

A year? A … year? Who am I if I’m not able to work?

I didn’t see it then but it certainly happened. The stroke became the punctuation mark of the long sentence that had been my life until that point. Not a comma, not a semicolon, but a declarative period that marks the end of a life as I had built it.

The sentence that lived before the stroke: Prove I can make a difference, even if that meant exhausting myself. The sentence that comes after the stroke: Nourish myself, and nourish the world in the process.

You see, I had so overdeveloped certain parts of who I was and so undernourished other parts. And that’s where all these puts and takes catch up with each other. And all the withdrawals I’ve taken were from one side: the need to be successful, the need to help others. And I’ve so deeply bankrupted who I am as a human that there’s nothing left to take.

GUNATILLAKE: There is real intensity to what Keith is sharing with us. It’s a lot. So please take a moment to just rest. Acknowledge any thoughts that are arising for you. It’s ok. Breathe how your body wants to. Listen.

YAMASHITA: As I live my way into the second sentence of my life, I seek nourishment. It comes in moments I don’t expect. It comes by being very in tune with the pain of others. Nourishment doesn’t just come in the format of joy.

“Miles, the rules are that I’m supposed to drop you off, and I’m not supposed to block traffic.”

“Dad, I want you to park the car and go in with me.”

He’s 12. It’s his first day of a brand-new school. He’s nervous. I’m nervous. In my old life, this is a day I would have never been present for. But now, I am here.

I park. We walk down the street together. Within 15 feet of the front door, Miles turns to me to give me a hug, and he starts to cry. He’s facing the entrance of the school and I am facing him.

I see all his new classmates walking by, one by one. My interior voice asks: Is this the best way for them to meet my son?

Not yet knowing his name, or he theirs, his classmates see him crying to his dad on the sidewalk. But Miles doesn’t care. He keeps holding me. And he keeps crying. And I realize: Miles can cry in a way that I never could. And he can seek comfort in a way that I never could.

I’ve so often been a person who would not stop, could not stop, because the moment I stop I would get very sad. And when the projects stop, when the conversations stop, when the ambitions stop, when the aspirations stop, sadness sets in. I have, in some way, spent my entire life up to this point trying to run out of sadness’s reach. And here I am with my son, just learning to sit in it.

I’m driving again. This time, my daughter, Coco, is in the shotgun seat. And the rule in our car is that whoever is in that seat gets DJing rights. She scrolls through the playlists on my phone and suddenly she stops scrolling. “Dad. You have a playlist called ‘My Funeral Songs.’ How morbid!”

I tell her, “I started this list before the stroke.” And I also think to myself, “What gay man in his right mind would trust his funeral songs to someone else?”

I really did start the funeral playlist well before my stroke. A friend dared me to. I keep adding to it. I pick songs that capture how I want to be in the world. It lets me spend time with this question: How do you want to be remembered for the life you actually lived?

That playlist gets a lot of use in these car rides. And they lead to other playlists, which leads to conversations and ideas, and worries, and squabbles between friends.These drives start to become a way for me to see my kids in a way that I never really did before.

In the midst of my recovery, I meet with an osteopath. I’m lying down on the examination table. My eyes are closed. His hands are cradling my neck and back of my head. He asks me to visualize a light source in my body. To make it easy, he says, “Just make it a light bulb. Okay, take that light. What wattage is that light bulb?”

“It’s a hundred-watt bulb,” I answer.

“Light bulbs also have dimmers. Is it up? Down?”

“It’s full on.”

“What wattage would it need to be to light up everyone in your life?” he asks.

“A thousand-watt bulb,” I respond.

“Why would you stop at a thousand-watt bulb?”

“I don’t know … Fine! An infinite-watt bulb.”

“Okay, turn the bulb in your mind into an infinite-watt bulb.”

His hands are on the back of my neck. I’m trying to turn up this light in my mind’s eye, and it’s really hard. I’m trying, and trying, and trying, and I’m not able to light it up to that level of intensity. And then, all of a sudden, it’s as if there’s this profound explosion of light. I feel it at a cellular level.

One one-millionth of a millisecond into that feeling, my doctor says, “Yes. Exactly like that. That’s the power you have always had,” he says. “You just don’t know how to control it. And that luminescence is you, and that’s what you are in everyone’s life. It’s time you learn how to harness it in a way that doesn’t exhaust you.”

All this time, I thought my recovery was about getting my face back. Getting my speech back. Getting my brain back. As I lie here, at the beginning of the second sentence of my life, I start to realize this isn’t a medical recovery. This is a spiritual awakening.

My story, your story, any story – really it’s about the images that we put into our mind’s eye. Do they nourish, or do they harm? I have been very actively shaping the images that I permit to enter my mind. I try to visualize being whole. I’m lying on my back, I am far at sea. It’s night. There are no stars. There are only clouds. When I turn my head there is no shore to be seen. The gentle swells of the ocean feel like the Earth breathing. And I am held.

I see myself from above. The farther I move out on the scene, I realize how small I am compared with the vastness of everything else. This is renewal: To know that I am held, but not at all in control. I don’t know what’s going to happen next. But it is about coming to love that mystery. I don’t know why, but I feel safe.

And this is where my story begins.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Keith has already said so much, so I’ll be brief. But first, if Keith’s story about setting course on a new direction in life is something you’d like to hear more of, I recommend you listen to an episode we released on April 2 last year by Franklin Leonard. It’s called “Writing the main character,” and it’s about how change happens, not in an explosion or sudden shift of scenery, but slowly, in moments of reflection, and sometimes after years of pleasing others. Again that episode is called “Writing the main character, by Franklin Leonard.” It’s worth listening to again, if you see yourself or someone you love, in Keith’s story.

And reflecting on his story and his words, one thing jumps out, one question: What’s important? So for our meditation together let’s sit, stand, lie down, or move with that question.

And before we do, just warming up, cooling down, opening out with a breath. And dropping the question into the mind: What’s important? And listening to the response.

There might be a clear answer, or confusion as to what I’ve just asked you to do, or something else. That’s ok.

What’s important? Right now, what’s important?

Sensations, thoughts, emotions, silence. What is your answer?

Each time we ask the question, each time we invite the answer, imagine unraveling, crumbling, revealing more and more subtlety. So, what’s important? Hold that question in the mind. And be open, listen to what arises. Again, that might be confusion. If that’s what’s here then that’s what’s here.

Asking a repeated question like this isn’t really about the answer. It’s about the stance of the mind, awake, subtle, charged, curious. What’s important?

Thank you. Do remember that because the experiences we share on Meditative Story can be so powerful, they can bring up all sorts of stuff for you. If that ever happens, do take care of yourself and do what you need to do to reset and reconnect.