Learning to see what is in front of me

A plant with nine blooming flowers. Or is it nine? Ten? No, nine. In the still, cold quiet of a museum hall, the author Siri Hustvedt sits. And looks. And sits. And looks. And sketches. Siri is known for standing in front of a painting for hours at a time and discovering elements that others don’t see – that she’s never noticed either. Why? Because expectation can prevent us from seeing what’s right in front of us. Our assumptions color what’s really there. You’ll never notice what’s right in front of you if you don’t look.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Learning to see what is in front of me

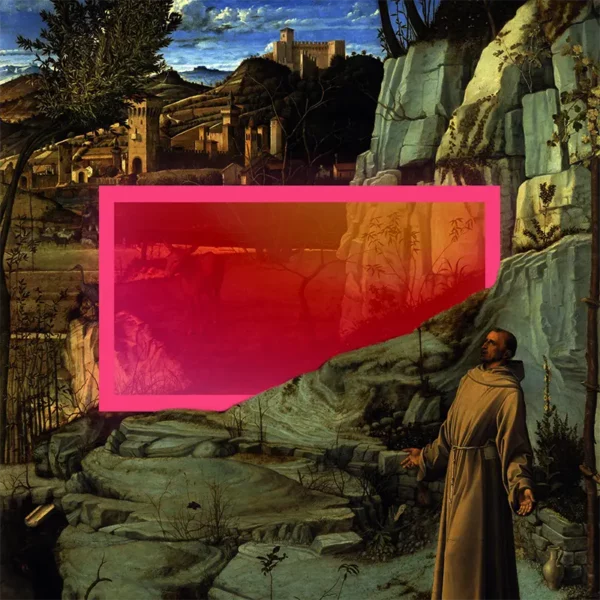

SIRI HUSTVEDT: A plant with nine small blooming flowers grows just behind Francis. I draw it quickly and then draw the wooden trellis to the right of the plant, the jug that stands in front of it, and the inclined desk behind it, on which rests a skull with no jawbone and a book.

As I draw, I feel as if I am touching each thing, tracing its outlines with my hand. I look up and think to myself that the Bible is the color of dried blood. Then I spot the monk’s sandals lying under his desk. He’s left his cane or walking stick behind him, too. It rests at an angle on one of the trellis rungs. The sandals and the stick are poignant. As I continue to look at them, I have a keen sense of ordinary life and ordinary death. Everything that is alive will die. Our things often outlive us.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Expectation can prevent us from seeing what’s right in front of us. Our assumptions color what’s really there.

Novelist and neuroscience scholar Siri Hustvedt is known for standing in front of a painting for hours at a time and discovering elements that others don’t see.

In this series, we blend immersive, first-person stories with mindfulness prompts to help you recharge at any moment of the day. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide for Meditative Story.

In today’s Story, Siri allows you to experience what it feels like to step inside a masterpiece and discover its hidden mysteries without prejudgments or expectations.

One way of understanding Siri’s story is that it’s about attention. More specifically, it’s about what can happen when we allow our attention – allow ourselves – to become immersed into one thing and what can be revealed when that happens.

But before we can immerse our attention, we first need to gather it up. So let’s do that. Asking yourself the question where in the body feels most steady right now? For me, it’s my breath. It’s gravity and its rhythm. Where is it for you?

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your eyes open. Your senses open. Meeting the world.

HUSTVEDT: I don’t know what will happen to me once I’m in front of the painting, but I know that if I let go of my expectations, if I open myself to the experience of looking closely, I may be surprised by what I discover. We are all creatures of habit, and most of the time we see what we expect to see. Our expectations are pre-judgments, after all, and sometimes they distort what is right in front of our eyes.

As I walk toward the building on East 70th Street that houses the Frick Collection, I tell myself to slow down. I tell myself that once I’m inside, I can take my time with the picture. I don’t need to rush. I tell myself the art is there just to be seen. All I have to do is look.

I have a single canvas in mind: St. Francis in Ecstasy. Giovanni Bellini painted it late in the fifteenth century. I know it’s famous, but I’ve neglected it. I’ve never read anything about it. All the better. I haven’t been told what to think or feel. I take several deep breaths, pull open the tall, solid door, and step inside.

I hear the clamor of conversations, see people milling in the hall, and worry that the museum is too crowded, but once I secure my ticket, walk down the hard marble floors of the hallway I turn right, and I feel my shoes sink into the carpet. It’s quieter here. People are speaking in low voices. The dark wood-paneled walls and the three tall draped windows on either side of the room let in diffused light. It’s grand but comforting. I hear a man and a woman quietly speaking Italian to each other. I hear the word bellissima.

GUNATILLAKE: It’s ok to take a moment to enjoy this lovely room. Feel the carpet, appreciate the quiet and the soft light.

HUSTVEDT: I make my way toward the Bellini in the center of the wall to my left, I notice several people gazing up at the painting, which I guess is about four feet tall and four and a half feet wide. I find a spot to stand. I watch two older women pause to look at it for eight or nine seconds and then move on past me. A man is standing close to the canvas, his collar up, his thin brown hair almost the same color as his jacket. I station myself to the right of him. I see the rather small figure of Saint Francis in the foreground. I see the tiny donkey behind him in a meadow, his ears pricked up, as if he is listening.

But I let myself feel the colors of the big, peculiar landscape first: the many shades of green in delicate foliage, curling vines, and grass; the deep and medium browns and ochres of branches and slender tree trunks and fallen leaves and the saint’s cassock; and the many shades of cool pale turquoise in the steep rock cliff. The whitening blue-green makes me catch my breath. I take in the strong hit of cerulean blue sky at the top of the picture and the white clouds that interrupt the color as they float above a walled city. I think to myself: This isn’t one place; it’s three places: the rocky mountain zone of the saint, the green meadow of the donkey, and the remote city on high.

GUNATILLAKE: The head, the heart, and your contact to the earth. Can you be aware of these three places all at once?

HUSTVEDT: I take out my notebook and begin to write. I hear two people speaking French as they pass behind me. The jutting stone face of the mountain rises above Francis and dwarfs him. As I focus on his body, I straighten up, inhale, and expand my chest. I realize I’m imitating the saint’s posture and smile to myself.

His hands are extended to either side of him in a gesture of reception, his upper body radiant in soft light. He looks awed but calm. There’s nothing wild or frightening about this man’s ecstasy. I’m afraid to stick my nose right up to the canvas. Instead, I lean forward, hoping I look inquisitive, not aggressive. I want to see his right hand. I think I can make out a tiny red spot. Stigmata. He has the wounds of Christ. One slender bare foot sticks out from under his robe.

The man in front of me leaves just as my discoveries are mounting. I spy a little rabbit looking out from a crevice in the wall to the left of Francis. I’m stupidly proud of finding the rabbit. I discover a heron not far from the donkey perched at the edge of the cliff that becomes the meadow. I make out another little bird far to my left. Saint Francis and the animals. I remember stories. Birds came to listen to his sermons. He once tamed a vicious wolf. Didn’t hundreds of larks swoop down from the sky as the saint was dying? I study the rock formations, and I seem to see hands, paws, hooves, and claws. I wonder if the painter intended to make this allusion.

A plant with nine small blooming flowers grows just behind Francis. I draw it quickly and then draw the wooden trellis to the right of the plant, the jug that stands in front of it, and the inclined desk behind it, on which rests a skull with no jawbone and a book. As I draw, I feel as if I am touching each thing, tracing its outlines with my hand. I look up and think to myself that the Bible is the color of dried blood. Then I spot the monk’s sandals lying under his desk. He’s left his cane or walking stick behind him, too. It rests at an angle on one of the trellis rungs. The sandals and the stick are poignant. As I continue to look at them, I have a keen sense of ordinary life and ordinary death. Everything that is alive will die. Our things often outlive us.

GUNATILLAKE: Imagine you were captured in a painting, just as you are right now, wherever that might be. What story would that painting tell?

HUSTVEDT: A guard approaches me. “You can sit if you like, ma’am.” He nods at a tall plush green chair decorated with pom-pom fringe right in front of me. His kind voice has jolted me out of the painting, and I realize I haven’t heard or seen anyone for some time. I thank him and sit down. It feels good to sit and lean back in the chair. I’m no longer facing the painting, and I let my eyes move across the room. The voices of the other visitors are suddenly audible again.

GUNATILLAKE: Widen out your sense of hearing. Apart from my and Siri’s words, what else can you hear?

HUSTVEDT: It’s as if I’ve been away. Before I walk out of the room, I check my phone. I’ve been in front of the painting for two hours. It doesn’t seem possible. I’m not thinking in sentences. I’m between worlds. I know that it takes a while to withdraw from a painting. I walk into the hallway and hear the percussive clicks of footsteps on the bare floor. Instead of heading to the coat check, I turn left and walk into the enclosed garden. Late afternoon sunlight comes through the opaque glass ceiling above me. I seat myself on a stone bench adjacent to the room I have just left and listen to the rush of water from the fountain.

My eyes land on one of two black frogs that shoot thin arcs of water from their mouths. I crane my neck and look through the window behind me. I want to catch a last glimpse of Bellini’s painting. I see it from a distance now. I feel a small pinch of grief. Grief for what? Am I sad to go? Have I suddenly remembered the brutal politics of here and now? Or is it time, the time represented by the skull? Saint Francis will stand there fixed in wonder as long as the painting lasts. I push myself off the bench and retrieve my coat. As soon as I open the door, the wind blows into my face. I hear a car horn, the squeal of a truck stopping, and I make my way toward the Q train.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: When Siri looked back at the painting as she prepared to leave, she felt a pinch of grief. But that was her. How do you feel? Can you sense into what emotion there is a pinch of right now? What name would you give it?

One of the most important things I’ve learnt through meditation is that how we see things, changes what we see. When we look at the world with relaxed, sustained attention, then our experience is different to when our attention is more scattered and loose. So let’s turn inside, and bring our attention to the canvas of physical, felt experience. What is painted here?

Dropping just for now the need to get caught up in thinking or planning. There’ll be plenty of time for that later. And really anchoring your attention in the canvas of the body. No need to grant distractions any power. Rest your attention with the body and allow whatever to appear.

What’s most obvious? Is there a sensation or area of sensation which stands out the most? The central character of your experience in this moment. Be it an area of tension, tingling, warmth or whatever, gently keeping it in your awareness, can you step closer and uncover more detail?

Now, letting go of this area, what else is here to be seen?

While the strongest sensations might call for our attention the loudest, what can you discover in the background? Let your attention roam around your body – to your hands, your face, your heart. Even to your eyes themselves. There is a universe of detail to be seen when we turn to it. What little details can you notice? What delight?

Now rest back and let your attention fill the body as a whole. Switching your awareness to be with the whole canvas of experience rather than caught up in one detail. Notice how different this feels. How united.

Siri spoke to us of how Saint Francis felt moved, his whole body open and in a gesture of reception. Full of awe but also of calm. Wherever you are right now, whatever position your body is in – moving, still, upright or otherwise – can it too be in a gesture of reception? A posture of grace, receiving whatever is here to be received. The simple sanctity of paying attention.