Showing up is never an end in itself

Best-known for his record-setting streak of 2,632 consecutive games played, Hall of Famer Cal Ripken Jr. is widely regarded as one of Major League Baseball’s greatest all-time players. But for Cal, just showing up is never an end in itself. It’s how he shows up that distinguishes his legacy as an athlete, a lesson Cal learns by observing his father – a baseball legend in his own right – whose dignity on and off the field extends far beyond hard work and fair play alone. Photo credit: CRJ, Inc.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Showing up is never an end in itself

CAL RIPKEN JR.: That’s my dad. He never puts any pressure on me to be a ballplayer. He doesn’t say I’ll be a star. He says, “You have God-given talent. Now you have to do the work. If you nourish it, you’ll get a chance to move on.” He wouldn’t say it if he didn’t see it, and it means the world to me.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Cal Ripken Jr. is widely regarded as one of Major League Baseball’s greatest all-time players. His Hall of Fame career spans an incredible 21 years, from 1982 to 1999, all with the Baltimore Orioles. Nicknamed “Iron Man,” Cal is best-known for his record-setting streak of 2,632 consecutive games played. But for Cal, just showing up is never an end in itself. It’s how he shows up that distinguishes his legacy as an athlete – a lesson Cal learns by observing his father, a baseball legend in his own right, whose dignity on the field extends far beyond hard work and fair play alone.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and stunning music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

RIPKEN: This summer we’re in Asheville, North Carolina. It’s 1973. I’m 13 years old. The baseball diamond is bathed in a yellow glow. Not a big crowd tonight – mostly wide-eyed kids like us, with their parents. The air smells of hot dogs. The National Anthem blares from the speakers behind home plate. I stand up, place my hand on my heart, and sing as loud as I can.

This is how we spend our summers, my mom, my brothers, my sister, and me. Whatever minor league town the Baltimore Orioles send dad to coach in, we follow.

Between innings, a spotlight shines on the mascot, Ozzie the Oriole, who drives a dirt bike out to right center field to change the scoreboard. He has a big old hat on. This is so glamorous to me. The field is like a stage that all the players inhabit. I want to be out there on that stage one day. I want to be a ball player.

After the game, we play cup-ball underneath the concourse while Dad showers and eats. When he’s done, he comes out and lets us play on the field.

The green grass blazes under the bright lights. We mimic plays from the night’s game, throwing grounders and fly balls to each other. I run the bases and try to count the steps it takes to get all the way around, but it’s too many. I make diving catches and slide in the dirt and work up a sweat. How I feel right now, the smile on my face – it really is the best thing in the world.

Mom has a job of it keeping the four of us in line. Lots of skirmishes to settle, lots of mouths to feed – and lots of clothes to clean. We do our laundry at a strip mall, a few blocks from the ballpark. There are never enough folding tables, so mom turns over our empty basket for a makeshift table. It’s hot, with no breeze, so we sit as close to the door as we can.

The four of us play a cutthroat game of hearts while she does the laundry. We’re all very competitive. And I have to win – at everything. Any way I can. I even cheat in Canasta when I play my grandmother.

In Canasta you draw two cards from the pile. Sometimes I draw four. Grandma has trouble with her eyesight. The way she holds her cards, I can’t resist looking over the top to see what she has. I’m so sure she’s going to realize I have twice as many cards in my hand than she does, but she never says a word.

The truth is, it just about kills me to win by cheating. It feels empty. I hear Dad in my head saying, “There’s no place for that.” He doesn’t believe in tricks or shortcuts. He believes in playing fair. I want to win because I’m the best. I start pushing grandma’s cards up so I can’t see them. And with my siblings I become a stickler for the rules.

In the laundromat, it feels like we’ve been playing for hours. I’m on a streak. Because I’m winning, my brothers and sister team up against me to stick me with the queen, which pisses me off. They don’t care about winning – they care about making sure that I don’t. That’s not how you’re supposed to play.

We get so riled up that Mom grabs us and sends us to the four corners of the laundromat to cool off. How exactly one person with two hands can grab four kids at once, I simply can’t fathom.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve dreamt of playing for the Orioles. I kept all of Dad’s rosters, schedules, and playbooks. Everything I know about the game of baseball, I learn from him. But not directly – from observing how he coaches the team. He’s only seen maybe 2 of my games in 10 years. He spends so much of the year on the road.

The Baltimore Orioles are considered one of the best organizations in baseball. Dad’s been with them for 14 years now. He’s a company guy, and he’s proud of that. But it’s hard to feed a family on a minor league salary.

Every time a coaching spot opens up on the big league team, the main office says he’s too valuable to let go. They need him in the minors developing young players. That all changes in 1976, when they finally move him up to the big leagues as a coach.

I’m 6’1, a junior in high school, 16 years old. Scouts from a number of professional baseball teams – including the Orioles – take note of me. When I tell my dad, he says, “We baseball guys can start to evaluate a player pretty well around the age of 16. You have a chance to play pro ball.”

That’s my dad. No expectations. He never puts any pressure on me to be a ballplayer. But he gives me hope. He doesn’t say I’ll be a star. He says, “You have God-given talent. Now you have to do the work. If you nourish it, you’ll get a chance to move on.” He wouldn’t say it if he didn’t see it, and it means the world to me.

Part of me doesn’t want to be drafted by the Orioles. I want to carve out my own space. I don’t want any impression that I’m being given something. But I know what kind of work I’ve put in. I’ve earned this myself.

So when the Orioles draft me in the second draft round, I’m proud to join the organization. A few months into my first minor league season I get hit by a pitch in the back of my hand and I can barely hold a bat. I call Dad and tell him I could use a day off.

Dad says “Well, you can do that. But what happens when the guy who replaces you gets three hits tomorrow? What do you think the manager’s going to do the next game? He’s going to play that guy.”

“So what do I do?” I ask.

“Don’t let that guy get three hits. Play. You want to be the everyday guy, every day.”

And from that moment forward, nothing keeps me off the field. It’s hard work playing every day like this. It’s a sacrifice. I see no one but my teammates. But there is something magical about playing in the Minor Leagues. All of us are in the same boat. There’s a camaraderie that takes place because we support each other’s dreams. But we’re still competitive. And sometimes the biggest competition is between me and someone else on the team who I don’t want to lose my position to.

Day by day, my hard work pays off. And in 1981, I get called up to the big leagues to join Dad. And by 1982, I’m the starting third baseman for the Baltimore Orioles. I play so well, I win Rookie of the Year. A year later I’m named Most Valuable Player and take home a World Series ring.

I’ve made it. And now I have to keep it.

In 1987, Dad’s named Manager of the Orioles. The position he’s worked for his whole career. But it comes at a challenging time for the team. In 1988, we lose the first six games of the season. Dad takes the blame, but as his son I wanted to fix things. If only I could’ve gotten a few big hits I could’ve reversed this whole downward spiral. We could’ve been 4 and 2 instead of 0 and 6.

It’s too late. Dad is abruptly fired, and I’m furious. Dad’s given his life to this ball club. He showed up, every day, with honor. Now I see what honor gets him. My warm, fuzzy feelings for the Orioles disappear. The organization is changing, and I don’t like the direction it’s headed in. It feels like nothing more than a business to me now. But I keep playing– and playing well – and eventually I cool down.

I have always wanted to be an Oriole. And now I have a history with the organization all my own. So when I think about where I can make the best contribution, what other teams I might help build, I keep coming back to the Orioles.

I guess I feel that leaving the team isn’t the answer. Showing up in a way that’s most meaningful to me is. And while I can’t do anything about Dad’s firing, what I can do is learn from Dad’s experience. I can be loyal to the Orioles and to me, both. Maybe it doesn’t have to be one or the other.

I’m in a hotel room in Cleveland. It’s August, and we’re in town to play the Cleveland Indians. The Orioles send their lawyer to negotiate my contract. I tell him I want certainty. That if the Orioles want me to commit they need to make a commitment back to me, with an absolute no trade clause.

In return, I say, I’m yours. Every day, every game.

GUNATILLAKE: And every breath. In meditation we also talk about this idea of showing up. Of being present, bringing awareness consistently, again and again, to whatever is happening. Can you commit, like Cal? Commit to this moment, to just being here in your body and mind?

RIPKEN: I meet legendary ball players like Ken Singleton, Al Bumbry, Jim Palmer, John Lowenstein, and a bunch of other guys – older guys. The conversation in the back of the bus often orbits around whether they’d do anything different if they could do it all over again.

I hear things like, “I wish I would have taken it more seriously,” or, “I wish I would have played more.” And I’m thinking, okay, I don’t ever want to have those regrets. There’s a game today. I can’t play tomorrow’s game until it gets here, and you can’t replay yesterday’s game. I can learn, but I can’t replay it.

After I sign my contract, I’m determined to conduct myself a certain way. Not only as a competitor, but as a fair competitor. To be a role model, like my dad.

This includes the way I show respect for the other team, even the way I wear my uniform.

One night our second baseman pretends to throw the ball back to the pitcher after a play, but keeps the ball in his glove so he can tag the runner out when he takes a lead off the base. It’s called the hidden ball trick. Amateur stuff, my Dad would say.

The runner on second isn’t paying attention, so I walk over to him and say, “Stay on the bag. The second baseman has the ball.”

My teammates are pissed, but I don’t feel that tricks are part of the game. I’ve always had a principle, whether it’s playing cards with Grandma or baseball in the big leagues. If things don’t turn out well, there’s a way to lose respectfully. And then you just come out and do better the next day. Day after day after day – preserving my honor on the ball field is as much a part of being a competitor as winning is.

I tell the second baseman, “You can do what you want, but I’m not doing it that way. That’s not how I play the game.”

GUNATILLAKE: There is a related concept in mindfulness known as radical honesty. In observing your own thoughts, you may notice things about yourself, or your responses to others, that make you uncomfortable, that you don’t admire. Try not to turn away from these feelings, or to judge yourself for them. Just for a moment, try to sit through your discomfort, and acknowledge how you truly feel.

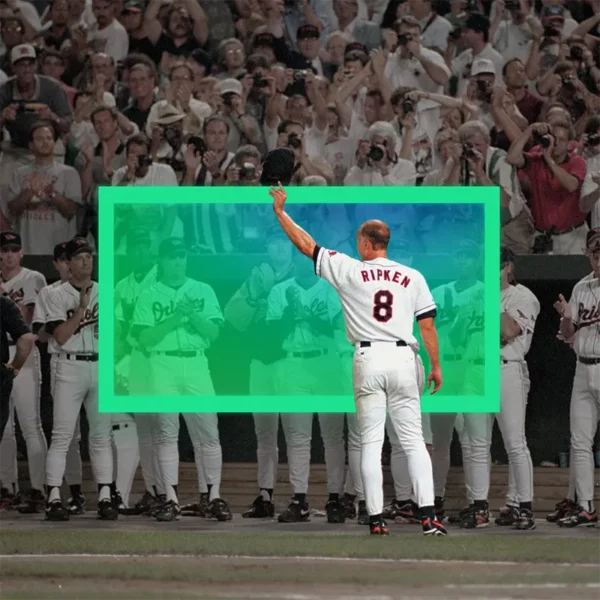

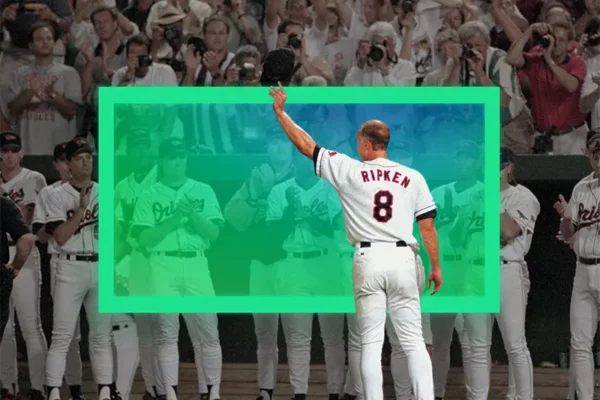

RIPKEN: It’s 1995. I’ve now played 2,131 consecutive games, surpassing Lou Gehrig’s historic streak. That’s thirteen straight years without missing a game. Not for rain, pain, illness, or injury.

At the crowd’s urging, I run a glory lap around the stadium. The crowd cheers for 22 minutes. One minute for every hundred games I’ve played. This should be an emotional moment for me – but even as I hear that roar, I feel conflicted.

I raise my cap to the crowd, but inside, I’m embarrassed.

Any perception that I’ve just set an attendance record is offensive to me. Showing up every day is just the right way to go about doing your job. Period. Showing up is table stakes. It’s not an end in itself – it’s what I do in order to compete.

That’s Dad’s message.

I put my feelings aside for a moment and allow the joy of the crowd to wash over me – appreciating the tens of thousands of fans who understand Dad’s message long before I do: How we show up matters.

Tomorrow morning, these kids in the stands will run a glory lap, like mine, in their backyards. They’ll mimic plays from tonight’s game, just as my brothers and sister did back in Asheville. The way I show up tonight may even plant the seed that blooms into tomorrow’s record-breaker.

For thirteen years I’ve shown up for the team, and for the fans – and for thirteen years they’ve shown up for me too. So I owe it to them right now. I’m not the only everyday player here. After all, right now I’m looking up into the faces of 46,000 of us, showing up together.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you, Cal. In just a moment, I’ll guide you through a closing meditation.

Knowing that Cal will be sharing his story I watched the footage from that game where he broke the record for consecutive appearances. It’s quite a thing. 22 minutes of the crowd celebrating his achievement. One minute for every hundred games to break the record. Cal shaking hands with fans, hugging friends, smiling, smiling.

A celebration of showing up. A celebration of always being there, present no matter what. It’s made me wonder if you’d like to try something with me for our practice together.

It’s a bit different to other meditations we’ve done so far this season but let’s give it a go. Let’s play.

Twenty two seconds: one second for every hundred games Cal Ripken Jr. played back-to-back, to break the record. Twenty two seconds. Letting your attention be relaxed, alert and bright, like Cal at third base. And showing up. Showing up for whatever appears in the mind and in the body, showing up for whatever comes into our awareness

Ok, how was that? Twenty two seconds can feel like a long time, or it can feel like no time at all. Either way, reset. Breathe. Feel your body. Feel the temperature of the air around you on your skin. And like Cal we’ll go again. Twenty two seconds. Seeing what happens. Knowing what is happening while it’s happening. That’s my favorite definition of mindfulness. Twenty two seconds of showing up, of being here.

Welcome back. Ok, for this last lap instead of going into the 22 seconds with the intention of bright awareness, let’s switch it up to celebration.

Bring to mind a time when you did something amazing, something worth celebrating. Or bring to mind the positive quality people tend to associate with you the most. For me, it’s being easy going. What is it for you?

Letting go of any self-judgment that might be here right now and choosing something within you to celebrate. And enjoying the warmth of that in your mind for this 22 seconds.

You did it. Thank you for trying that with me. As you dismount from this meditation into the rest of your day, take a moment to reflect on how that was for you. And if you enjoyed the practice of taking 22 seconds at a time to reconnect, to be awake, to celebrate yourself, then why not try it again when it next comes to mind.

Thanks Cal, and thank you.

Go well.