Creative potential is everywhere

Jon Foreman is a land artist who uses the raw materials of the environment to create breathtaking ephemeral pieces. His ability to see creative potential all around him is his superpower, but when his life presents him with the unexpected, he has to become more narrowly focused on his responsibilities. In today’s episode, Jon tells the story of how he eventually finds his way back to his creativity, and gives himself grace for the times when his life is otherwise full.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Creative potential is everywhere

JON FOREMAN: I grab bits of string, paper, cardboard. I have no idea what I’m gonna do with them, but I start arranging them and rearranging them. I start taping string to a tin can, over and over, one piece of string at a time. The process becomes repetitive. But it’s soothing and fun. As I connect the objects to other objects, I make something totally new. Something that’s never existed before. With this process, it’s like a part of my brain is reawakening.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Professional land artist, Jon Foreman, creates incredible works of art out of sand, leaves, and other natural materials in the environment. But his impressive ability to see creative potential all around him is tested when, as a teenager, he has to become more narrowly focused on his responsibilities. In today’s episode, Jon shares the story of learning that the world’s creative potential is always all around us, waiting for us, whenever our lives open us up to it.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open, your mind open, meeting the world.

FOREMAN: I glance over at my group of friends gathered nearby. We’re all fifteen years old, and we dress alike: black jeans, band t-shirts, long hair. Alternative, goth, punk, metal — whatever you want to call us. Because of how I look, people think I’m into drinking or drugs. But I’m not. I’m interested in designing creative ways to pass the time. And I just like to be outside.

We’re in a public park in my hometown of Milford Haven, Pembrokeshire, Wales. The slope below us is divided into a series of small terraces. I see a tall white wall in the distance. Just beyond that, there’s a big drop, and then, the blue-green sea.

I call out to my friends. “Ready?” I want to make sure they’re watching. One friend takes out his camera to film. I scan my surroundings and plan my approach.

My friends and I are out here doing parkour. It’s sort of a sport, and sort of an art form. We run, jump and climb over whatever obstacles are in our environment, anything from stairs to sides of buildings.

Looking around, I use what I like to call “parkour vision” to imagine what’s possible. I see a low wooden ledge that I can flip off. A railing I can step off. And a platform where I can take a flying leap.

My gaze lands on a large wall. It’s a perfect spot to try a wall spin. It’s like a sideflip, but with your hands on the wall. It feels more creative than a typical frontflip. I think I’m ready to try it out.

I give myself a little space. Then I run right up to the wall. I jump, and my hands meet the wall at chest height. For a moment, I feel the cool cement beneath my palms. I pull my body round with my higher right hand and push off the wall. I tuck my legs and twist with the momentum of my body. The world spins for a second as I go upside down. And then my feet land solidly on the ground.

Yes! I’ve got it! I hear my friends cheer. It feels good. I savor the movement.

Parkour is all about seeing what I can do with what I’ve got. My surroundings are my canvas. I get to imagine and design whatever I want to do in the space.

I’ve been out here since 10 AM, and I’ll probably stay out here until 11 at night. Running, jumping, skateboarding. If I stay inside too long, I get irritable. Winters are tough. When the weather’s bad, I can’t go out. I get frustrated. I just need to move.

I’m 15. I don’t think much about my responsibilities or limitations. My world is wide open. And I have no idea that, pretty soon, that’s all going to change.

I stand in the empty hallway of my house. My chest is tight. I try to steady myself by staring at the wall. It’s painted faint green. I’m preparing myself for a conversation I know I need to have. I get anxious just thinking about it.

I’m sixteen years old, I’ve recently found out that my girlfriend is pregnant. I’m spinning from the news. It’s a lot to process. But right now, I have to tell my mom that I’m going to have a kid. I don’t know how she’s going to take it. She’s quite Christian. Sometimes, when I have to say things to her that I don’t want to, I just text her. But that feels a bit cowardly for something like this. I need to tell her in person.

I see my mom coming down the hallway. She’s just over five feet tall. She wears jeans and a bright jumper, and her brown hair is cropped. She looks up at me through her round glasses, and smiles. I take a deep breath.

“Mom, I need to tell you something,” I blurt out. Her smile falters. She can hear how serious I sound. I don’t ask if we can sit down somewhere. I just need to get this out. Now.

I tell my mom the news. Shock spreads over her face as she comprehends that I’m going to be a dad at 16. I know this must feel out of the blue. I’m usually a sensible kid.

Her shock quickly turns to disappointment. She’s not angry. She’s just not happy. This is a difficult situation. My whole family is meant to move to North Wales soon, about four hours away by car. My dad is a vicar, so he has to move for his job. But even if my parents have to go, I know I need to stay here in town. I need to be close to the baby.

My mom starts to go into worrying overload. Where will I live? How will I take care of a newborn when I’m just learning to take care of myself? I don’t have answers to any of these questions.

In my sixteen years of life, I’ve been able to spend a lot of my time doing the things that I like. But I can’t just think about myself anymore. I’ve got to do what I’ve got to do to be a father. There’s no backing out now. It’s almost as if parts of my brain that were previously open are closing down. I have tunnel vision. This is going to take all my energy.

GUNATILLAKE: We can have one of two responses here. One about focus and dedication. One about the loss of opportunities. Notice which your mind is drawn to. Interested in that, but without judgment.

FOREMAN: A cool wind blows the dried leaves across the ground. I gently push the pram ahead of me, hoping the bumps on the path don’t wake my one-year-old son, Alijah. I balance a couple of shopping bags on the pram’s handle. Shopping is a pain in the neck without a car, but I can’t drive.

I look around at the houses in our neighborhood. They’re all square. Each has a sideways slanted roof and identical sets of wooden stairs. Everything is painted the same color. The whole atmosphere is dull. Not pleasant. A bit rundown. There’s crime. But it’s all I can afford at the moment. I share custody of Alijah with his mom, so he’s with me half the time. I’m 17 years old.

Finally, we make it to our flat. The familiar smell of mildew hits my nose. On the right is a bathroom, and then a room with my bed and Alijah’s cot. I live in a bed-sit, a single unit within a shared property. It’s so small, when I moved here, someone advised me to have my son sleep in a cupboard. But I won’t do that.

I look down at Alijah, asleep in his pram. Everyone says he looks like me. He’s got his mom’s eyes. And he’s quite chubby. A very cute baby. I hope he’ll sleep a while longer before I have to feed him again.

When Alijah’s born, I try to be as ready as possible, but I’m not ready. Is anybody? I learn as I go along. I know how to sterilize bottles and that sort of thing. My parents call every other day, and they come visit when they can. But since moving away, they aren’t around the corner anymore.

One of the hardest things for me is that I’m not able to go outside like I used to. And being stuck inside for long periods just makes me feel bad.

The time I get to spend with Alijah is so important, but I don’t really have time for myself anymore. I have so much I need to do. So much to take care of. Sometimes, the constant responsibilities almost feel like imprisonment. It sounds dramatic, I know. But at seventeen, it’s frustrating.

But I just deal with it. I’m determined to do what’s necessary.

I used to be able to have “parkour vision” and see creative potential everywhere. But I look around our dingy flat, and it doesn’t spark anything for me. My world has become limited. How will I ever get back to spending my time outside? I haven’t given up on wanting the creative freedom I once had, but I don’t know when I’ll have it again. Right now, I’m just trying to get by.

The large classroom is filled with easels holding giant sheets of paper, packed with every medium you can think of. Charcoal, paint, sculptures. It’s quite chaotic. The walls are covered with all the things we’ve each been working on. Although chaotic, the space doesn’t feel negative in the slightest, it’s pure creative energy. All my classmates are absorbed in their art. My friend Jamie is in one corner doing digital work on a computer. Holly is in another corner doing an oil painting.

I’m in my first year of college. We call it foundation year.

Recently, this studio has become a haven for me. Alijah is 2 years old, and I still split custody of him with his mom. On the days that Alijah is with her, I’m here at college. It’s a welcome break from my responsibilities at home.

Our tutor, Rich Brooks, walks about the room. He wears all black, no logos, as usual. He says it’s so that when people looking at him, they see him, and not what he’s wearing. As our teacher, he’s very encouraging and supportive. We explore. Jump into new things and chase ideas.

Our tutors push us to contemplate difficult questions like: Can you teach creativity? I believe everyone is creative. Rather than teaching creativity, my tutors draw out the creativity that already exists in each of us.

Partway through class, he calls us over to the center of the room. He stands before a table that’s covered with loads of random stuff. Plastic bottles, tin cans, some string, and some paper. “Respond to these materials,” he says. I can see on the faces of a couple of my classmates that they’re not all excited by the idea of making something so spontaneously. But I am.

I grab bits of string, paper, cardboard. I have no idea what I’m going to do with them, but I start arranging them and rearranging them. I start taping string to a tin can, over and over, one piece of string at a time. The process becomes repetitive. But it’s soothing. And fun. As I connect the objects to other objects, I make something totally new. Something that’s never existed before. With this process, it’s like a part of my brain is reawakening.

These materials are nothing special. They’re things I can find around me at any time. I realize, you can literally use anything to make anything. I’d never thought about art this way before. This is the most open and free thing I can do, and it’s all just right here. Like it’s been waiting for me.

For the rest of my foundation year, this is all I do. I take old objects that I find in the college, like easel boards and tables, and I arrange them into things. I get a lot of packing tape and I wrap it around itself to make what looks like floating plants hanging from the ceiling. I take an old Mac computer tower and break it up, creating art with the pieces. I have no worries about what the end result will be. There’s a rhythm to my work. I’m in the zone.

I’m quite relentless in everything I do here, including researching different artists and different mediums. While exploring, I come across Land Art. Land art involves using natural materials from the landscape — rocks, sand or leaves and sticks. It means creating art in the natural surroundings. I know I love arranging objects, so it makes sense to take advantage of the amazing environment around me.

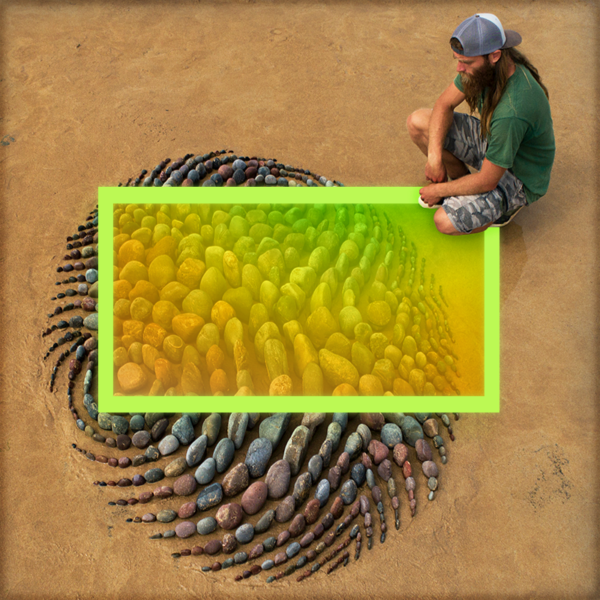

I live on the Pembrokeshire coast. It unfurls with pale rugged cliffs, the sea is a blue/green. I still yearn to be outside. To hear the ebb and flow of the ocean. As a land artist, I start to create large scale stone works and massive drawings in the sand that sometimes cover the entire beach.

All of this work, it’s an escape from the messy day to day home life, bills and the endless responsibilities at home. The sensation of being trapped … it lifts.

I’ve oriented so much of my recent life around fatherhood, and I wouldn’t trade all my time with Alijah for the world. But now I realize the potential to express myself creatively and to shape my world in whatever way I want. It’s always been here, waiting for me to be ready again. And I’m ready now.

GUNATILLAKE: What is something in your life that you feel you are unable to access? How true is that? Like Jon, can you sense its potential, its constant presence, however quiet that might be?

FOREMAN: We park the car and I walk across the little footbridge into the woodlands. I hear the sound of rushing water before I see it. I walk up the short path. Leaves crunch beneath my feet. There it is: the waterfall surrounded by trees.

Alijah runs ahead of me, full of energy from being pent up in the car. He’s fourteen now. We’re stopping off for a break on our drive up to visit my parents in North Wales.

I reach down and pick up a nice flat piece of slate with a jagged edge. Then another. We’ll use these flat stones to make art. I’ve been doing land art since 2011. It’s become my life’s work. Alijah is my life’s work, too. Most of the time when we go out to do land art, he kind of does his own thing. But today, we’re making a piece together.

Alijah runs off to gather more pieces of slate. I arrange them by size. Slowly, a form takes shape.

As we work, listening to the sounds of waterfall, I think about how glad I am that I stayed in the town where my son was born. If I had moved up to North Wales with my parents back when I was sixteen, I would have missed out on so much. I would have missed the caves and beaches and natural beauty of Pembrokeshire, which inspired me so much to become a land artist in the first place. I would never have created this life outside, under the sky and by the sea.

I try to go out to create work about three times a week. I still can’t spend too long indoors. The brilliant thing about being out here is there’s a physicality to it. There’s movement in the creativity. It’s inherently therapeutic and meditative, whether it’s placing a stone in the earth, or dragging a rake through the sand, or feeling the touch of a leaf.

And of course, if I had moved away, I would have missed out on the greatest gift: time with Alijah. I had a lot of struggles as a young father, but I’m thankful for it all, and for where it’s brought me.

Alijah places a piece of slate next to the ones we’ve arranged so far. The stones sort of interlock. They start to form a spiral. As we build, the pieces of slate get bigger, which creates a sense of depth, as if the spiral is going into the ground. It’s not a conceptual piece. There’s no point we’re trying to get across. If I were to create meaning for all of my work, it would quickly become forced. Each person who sees it will generate their own meaning.

As the minutes stretch on, Alijah struggles a bit with staying focused. But he’s done such a great job. We’re both really pleased with how it’s turned out.

It’s great that Alijah enjoys being outdoors, experimenting, and being creative, but I know he’s not going to be just another me. I want him to embrace the freedom to shape his world the way he wants to, to know that he can make anything from anything. That potential for creativity is all around him, whenever he needs it.

I’ve come to see that it’s true for all of us. There are chapters in all our lives when things pile up, when we don’t have energy for much else beyond maintaining our responsibilities. And that’s okay. There are times when we have to tend to our lives and keep our focus narrow. And there are times when the horizon opens back up. When the ability to make something out of anything becomes more visible again. We have to be patient for those opportunities, and seize them in whatever way we can to let our souls breathe.

Be patient with yourself for the times when your life is full, when there’s overwhelm. The potential for creative expression is always around you, whenever you’re ready for it.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you, Jon.

You know, when Jon talked about his parkour vision, the ability to see the environment all around us as full of possibilities for movement and play, I totally got it. Actually, I more than totally got it. Because it was parkour that first gave me the inspiration to my approach to mindfulness. I used to work in a part of London called SouthBank, where back in the early/mid 2000s, a lot of the London parkour scene would hang out. So, on my lunch breaks I would watch them all doing their thing, and it got me into the question: “what does urban meditation look like?” Like the free-runners, what would it be like to use everything in my environment to build my awareness, calm, and kindness? A question which opened my mind and my horizons, and one that ultimately led me to being here with you.

I also totally got Jon’s perspective on what it is to be a parent. As the father of two fairly small kids, much of life does feel like treading water. Having just enough energy to do what it is we need to do to get through the day. It’s a very different mode of being to parkour vision. It’s much more narrow.

All of which means, for our closing meditation together, I’d like to invite you into exploring these two modes of being. Let’s start here with the narrow.

It’s worth noting that narrow doesn’t mean inferior, it just means narrow.

So let’s get into it with your breath.

Start by locating the breath wherever it is most obvious.

Maybe in the chest.

Maybe in the belly.

Finding the breath in the body by knowing its sensations.

And making these sensations of the breath the most important things in the world.

Narrowing our awareness to include only the breath.

You could call it narrowing, you could also call it deepening.

Knowing what it’s like to have a narrow, deep mind.

One that is able to soak up a lot of fine detail about one thing.

And when the mind gets distracted, just dropping it back into the sensations of the breath.

Narrow. Deep. Now let’s explore wide.

Wide like parkour vision. And for this, we use hearing.

Moving our awareness to rest with our sense of hearing.

Relaxing the face and relaxing the attention.

Unlike the narrow focus of the breath sensations, now we’re just being open.

Instead of going out to get experience.

We sit back, lie back even and receive it.

Here. Mind wide. Awareness open.

Resting with hearing. Receptive to all possibilities. All potentials.

Knowing what it’s like to have a wide, open mind. One that is able to contain a multitude.

As part of my preparation for this episode, I spent a good amount of time looking at Jon’s land art. It’s really a wonderful thing and totally worth checking out for yourself.

And what I noticed was that it contained both narrowness and width. Depth of practice and craft, balanced with an appreciation for the vast landscape and for nature.

So as we finish, can we play with what it might be like for the mind to be both narrow and wide at the same time.

Like many things in mindfulness, that might not make sense logically.

But it might make sense experientially.

So give it a go.

A mind that is wide and narrow, narrow and wide all at once.

Embracing the possibilities all around us. Focusing into the right here.

Thank you, Jon.

And thank you.

We’d love to hear your personal reflections from Jon’s episode. How did you relate to his story? You can find us on all your social media platforms through our handle @MeditativeStory, or you can email us at: [email protected].