We become the places we love

As the wind howls around his camping caravan on a remote Welsh farm, poet David Whyte sits at a table, trying – and failing – to write. He’s worried he has lost his gift. He’s worried he never had a gift at all. But just outside, invisible and unexpected, is someone who offers him help – and friendship – at the exact moment he needs it. Their lifelong friendship takes root here, in the magical, windswept landscape of Wales, where place-names are poetry, where memories live long in the rolling hills.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

We become the places we love

DAVID WHYTE: There are many winter nights when the wind comes up the Ogwen Valley below and threatens to blow my caravan away. I am not easy on myself beneath that wind. I am having a really difficult time and feeling very, very sorry for this young man who wants to become a writer.

I need help, I remember saying I need help. Visible and invisible help.

Invisible help is the help that you do not as yet know you need. Sometimes that help appears and you walk right past it. And other times you actually recognize it. And this invisible help is one day suddenly made visible right outside of my caravan.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: As a poet, David Whyte uses words to bring light to our deepest human feelings and impulses. Poetry, he says, is “language against which we have no defenses.” He is the author of 10 poetry collections, as well as celebrated nonfiction addressing the transformative nature of work, heartbreak, and identity.

In today’s Meditative Story, David shares experiences from a magical time when he lived in the Welsh mountains, when he was just coming into his own as a poet. Sharing stories of truths that are both ethereal and yet wholly grounded in the wisdom of the land and its people.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

WHYTE: I’d like to take you back in my mind and in my life to a remarkable, almost mythic place that acted as both a portal, opening the door to the next stage of my life, and a deepening of my self-understanding: as a poet, as a philosopher, and in the end, as a man on his way to some sort of maturity with regard to friendship and that very particular friendship we must all make, with both heartbreak and the disappearance of our loved ones.

That remarkable, mythic place is a little farm tucked away under a mountain in North Wales: Snowdonia, as it is commonly called, but perhaps, more accurately in the Welsh language: Eryri, “the mountains of longing.” North Wales initially becomes my home, because I attend university there to study marine zoology, climb its mountains, and eventually fall in love with its hills and vales and the tenacious way of life and language of its inhabitants.

Soon after graduating, life and luck takes me away to the Galápagos Islands, but armed with my scientific knowledge not as a question but as a weapon almost with which I would subdue the ecology of the islands to my naming, my understanding, and my organizing powers as a scientist. A second Darwin, perhaps.

Only a few short months into time amongst the bird cries, the incoming waves, and the disturbing everyday inter-animal violence of the life there, I find that none of the animals or birds have read a single zoology book that I have read. That they have lives and secret selves unmediated by human classification and naming.

To my consternation, I find that I am really not equipped with a language to describe what I am experiencing: most especially the imminent sense of death and disappearance that is present in those islands. One evening on the boat I am guiding, staring at the swift falling equatorial sunset, I find myself quietly unraveling, my firm sense of self with which I had reached the islands, broken apart by the complex interwoven immensity of what I was witnessing. For a while, in those islands, I am just barely holding on to the fixed sanity I brought with me.

But not just witnessing. One other day, three months into my time there, I am on a new boat as a guide, with a new crew who have still not accepted me, with new people who are irritating me, with a newly woken, more vulnerable me, not knowing how to fit anywhere in the world, natural or human, and I have to say, walking along, feeling a little sorry for myself. To comfort myself with some sort of insulated aloneness, I walk 20 paces ahead of everyone along the path, and there on a branch right across the path, at eye level, I come across an unblinking, unmoving guardian to the secret of my future life, and in a way, the work and the writing I will do in that life.

Staring straight at me with tawny yellow eyes, feathers ruffling in the morning breeze, a Galápagos hawk.

I stop, everyone stops behind me; the hawk just stays there looking back, swaying slightly on its branch, yellow hawk eyes staring into my brown human eyes. I stop, and I stare back. I am looking into the essence of hawk-ness in the world. I am looking straight into the well and the depths of its eyes, I am looking at that corner of creation which laughs at any manufactured name we have given it, but is hawk-ness itself. Time stops its linear procession and begins to radiate from where I stand. I feel simultaneously a physical, body unravelling and a sense of revelation all at the same time. The surprise in the revelation is that I have the experience of the hawk looking just as deeply into that corner of creation that I occupy in my humanity. But it is looking straight beneath any surface personality, any David Whyte-ness and straight to another, unnameable foundation that I am just beginning to understand.

Many years later, I look back on that fixed image of the hawk as a guardian to the temple of the self – which once we enter the temple is, actually, no fixed self at all. But a moving conversation.

The encounter with the hawk is the first of a series of ever deeper steps into the conversation every human being discovers and is initially frightened by, between what you think is you, and what you think is not you. It is the ancient, conversational dynamic around what seem like two opposing poles, and one every great contemplative tradition has centered its disciplines around.

In Galápagos, I am in effect on a kind of 18-month meditative retreat. Though … real meditation is no retreat at all, it’s just a deeper form of attention. So, I have 18 months of meditative (that means, traumatizing, atomizing, and reintegrating) tearing apart in the Galápagos Islands.

I return to North Wales on a cold October day, the wind like a knife off the Irish Sea, felt very keenly indeed after two years in South America. I am returning to Eryrie, those mountains of longing, not knowing what I will do in the future, as a scientist or an artist. I come back to a small farm I had always loved as I had passed it in previous years, with an accurate Welsh name, Tan-y-Garth, Tan-y-Garth Farm, meaning, in essence, “halfway up the mountain.”

I come back to this place halfway up the mountain in Wales almost in retreat, to try and find out who is here after that extraordinary experience in those far-flung Islands. I’ve lived out everything I want to do as a scientist. How can I follow that? I start writing. I am in some way, like the classic Vietnam veteran, hiding away from the mainstream, except I had not been traumatized by violence, I had in a way been traumatized by beauty, the island sights still filling my dreams and its sounds still ringing in my ears.

I move into a tiny caravan on the farm, a tiny freezing caravan, looking out from the mountain, facing Ireland and the wind. I live there, I work there with John, the Welsh farmer. and his 900 sheep on the land that spreads right over the Carneddau Mountains behind me. In the evenings, I write.

GUNATILLAKE: This is a scene. Take some time to imagine David here. I know the land of Northwest Wales a little bit so I can see it. What do you see? Let the space, the big skies soften your shoulders.

WHYTE: I spend a good year there, digging the animals out of snowdrifts: lambing and shearing, dipping the sheep helped by the extraordinarily well-trained sheepdogs owned by John. John has a fiery Welsh temper, an impressively wide lexicon of Welsh swear words, and an almost biblical shepherd’s crook. Even in his worst temper, he never hits a dog; his aluminum crook is bent, however, from hitting stone walls in frustration as he instructs at high volume across the fields. Somehow he manages to produce some of the best dogs in North Wales. People come from far away to buy these dogs.

There are many winter nights when the wind comes up the Ogwen Valley below and threatens to blow my caravan away. I am not easy on myself beneath that wind. I am having a really difficult time and feeling very, very sorry for this young man who wants to become a writer.

I need help, I remember saying I need help. Visible and invisible help.

Although we associate invisible help with unseen parallels, I always feel that invisible help can actually be interpreted in a very practical way. Invisible help is the help that you do not as yet know you need. Invisible help is the help that you do not as yet know you need. Sometimes that help appears and you walk right past it. And other times you actually recognize it. And this invisible help is one day suddenly made visible right outside of my caravan.

We are a little community at Tan-y-Garth. Besides the main farm, there is an older cottage which is tucked into the very rock itself, a cottage whose back wall is the living rock of the mountain. 400 years old? 500 years old? Probably the original farmhouse. A new family moves into this cottage. And I notice that the father in the family is employed to do work around the farm that I am not doing. So, I see him every now and again, off in the distance.

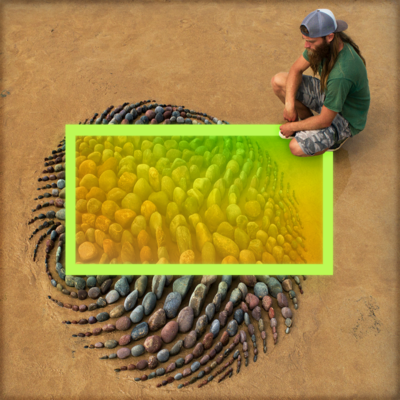

One day I am writing, or more accurately not writing at my table, when I hear a great deal of noise outside of my caravan window. I look out, and there’s the gentleman I have only seen at a distance. He’s in his early 60s, but very, very spry. And he’s trying to rebuild a stone wall that has fallen. You could spend your whole life rebuilding stone walls around Tan-Y-Garth farm. The rebuilding of a stone wall is no easy task; it actually has five components. There are two outer walls, one on each side. There’s an inner fill of rubble, there are stones called throughs that go completely from one side to the other, and then you’ve got a stone upright layer on top.

I am looking out, and I can see that he does not know what he’s doing. And I’ve done enough stone wall building myself that I can tell that this is not going to end well. There is an unstable, Dr. Seuss-like wall tottering up outside of my window. I am trying to concentrate on my writing. And I say to myself, “Will I go out and tell him? I won’t, I won’t.” But eventually in the end, relieved to have a break from not writing, I say to myself, “I’ll put the kettle on and make him a cup of tea for when he’s finished.”

I walk out with the two mugs of tea. And I say, “Good morning, I’m David. David Whyte. And nice to meet you. I’ve seen you around the farm.” He takes his gloves off, looks me straight in the eye, and grabs the tea. He says, “Oh, thank God for that. I’m not doing very well at this.” And he puts the mug of steaming tea down for a moment on top of the wall and the whole wall collapses with the mug of tea inside it. And we look at each other, we grin, and I say, “Come on then, let’s build this wall together.”

And that’s how Michael and I begin to get to know each other. Michael Higgins.

Michael and I have real conversational chemistry: Every evening, I go across to his small family cottage to sit with him by his coal fire. His wife, Diane, is a very religious woman, and she has herself and the kids to bed by 8:30 every night. So Michael and I sit by the fire with a glass of illicit brandy, brought out of a cupboard when the coast is clear, and every evening we start to talk, and as we talk, I begin to realize that Michael is actually more of a realized artist than I am. It turns out he’s an engraver, and a really remarkable engraver. He starts to show me some of his work, and to my mind, looking on with my mouth open, as good in the fire light as anything I have seen by William Blake.

I open my heart to him around my difficulties in writing, how I’d written since I was small, how I used to have the magic, and I don’t seem to have it anymore. And then, Michael listens, offers his warm advice, and then he opens his heart to me.

Michael has a long, long Celtic face, with all of these horizontal lines across it. And this face is really the picture of doubt at times. Michael’s genius in a way has to do with asking really fierce, doubting questions. That, I’m beginning to discover, is Michael’s essence: to doubt. When he turns this face of doubt upon me in the middle of a declarative sentence, I find myself caught in the gravity-well of that doubt, I find myself backing out and contradicting myself before I get to the end of the sentence.

But every evening, I feel that Michael’s doubt is built on a foundation of true sincerity, the doubt of the true question, not the doubt of cynicism. It is the doubt of really wanting to know if what you were saying was true. Is it really true that you can’t write? Is it really true that you once had the magic and have lost it?

And Michael has his own, in many ways, more beautiful question. Michael himself is a great follower of the poet and artist Blake, William Blake, who is one of the finest engravers who ever existed, and who had his own inimitable style. And Michael’s beautiful and disturbing question, which he asks almost every night, and usually after taking a good sip of brandy, is: did Blake actually converse with the angels or is it just a metaphor that he stood in conversation with worlds beyond our own? If you know anything about William Blake, you know he spent a lot of time talking with the angels.

This, I discover, is a key question for Michael. Did Blake actually speak with the angels? Or is it just a metaphor that we stand in conversation with invisible worlds, larger than our own? Are there other invisible parallels? Is there another source of help in our life?

GUNATILLAKE: I’m not going to tell you my own instinctual answers to these questions. But what are yours? What comes to mind as David asks them? Watch them come. Watch any reaction to them come. Breathe.

WHYTE: The other thing that Michael says almost every night without fail is, “You know, I love this place so much. I think I found my place to die.” He meant Tan-y-Garth, of course, and the mountains surrounding, and the fields, and the valley leading off toward the island of Môn in the far distance.

Above, you have the Drosgl Ridge, starting literally in the back wall of this cottage: an enormous curve leading straight into the Carneddau Mountains, culminating in Yr Elen, which in Welsh means “the shining light.” Its steep face often reflecting the evening light through the mist.

One day we are above the waterfall at Aber, sitting quietly with one of the dogs, looking down over the Irish sea. Out of nowhere he turns and looks me in the eye just as he did when we first met. He says, “This is the place I want to have my ashes scattered.”

From Tan-y-Garth, I go off and travel and come back. One year I go away, and I don’t come back: I go to North America, and I make my home there. Tan-y-Garth remains in my mind, irradicable, the sound of the ravens over the farm. The sound of the mothers bleating, on the night they are separated from their lambs. I become a writer.

Many years later, I am back in North Wales: in Eryrie, but I am driving through, heading for the ferry to Ireland. And suddenly I realize on the road, I actually have time to stop and walk up to Tan-y-Garth farm on my way over. There is no phone then on the farm. So I drive up as far as I can, and then I walk a good half mile up through the fields.

As I near the door of the cottage and see my old caravan still nestled just a field away against the wall that first brought Michael and I together, I catch the gorgeous smell of freshly baked scones coming out of the door. And Michael’s wife, Diane, who has seen me coming up the fields, acts as if I have never been away: she smiles and says, “You’re just in time.” She follows it with, “Bachelors timing,” as she pours the tea and brings out those fresh scones. I look around, and I say, “Where’s himself? Where’s Michael?” And there is a long moment of hesitation until she says, “I’m afraid he’s in hospital overnight for tests.” I say, “Oh dear, no.” She says, “Yes, it’s quite serious. He’s got leukemia.”

And I can’t stay, tea, scones, a hug, a tear, and I am off, and I actually don’t come back the same way from Ireland. So, I go back to the States, and I never see Michael again. A few months later, I receive a letter from Diane saying that he’s passed away.

Despite the sad news it conveys, the letter is incredibly moving, and beautifully written: Diane says that he had a remission for a few weeks before he passed away. He was home, he was back on the farm. And he was walking around those fields beneath the mountains he loved, she says, experiencing everything he had read in Blake. Michael had his conversation at last with the angels, every day before he died.

“Tan-y-Garth (Elegy for Michael)” by David Whyte

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you, David for such an evocative story. I have spent some time in the Welsh hills and now long to go back.

This week, for a slightly different ending to the episode, rather than a meditation from me, it’s such a treat that David is going to tell us a poem for Michael – and from that time in his life.

David, why don’t you introduce it?

WHYTE: I can’t make it across the Atlantic so quickly for the service; so I have my own service: I write this elegy for Michael, and it’s called Tan-y-Garth (Elegy for Michael).

This grass-grown hill’s a patchwork lined with walls

I’ve grown to love. Four hundred years at least the

hill farm’s clung tenacious to the weathered slope,

over the Ogwen and the green depths of Môn.

The eye has weathered also,

into the grey rocks and the fields bright with spring,

the wind-blown light from the mountain, filling the valley;

the low backed sheep following the fence,

hemmed by dogs and John’s crooked staff,

the still valley filled with his shouts

and the mewling of sheep pressed through the gate.

Beneath Yr Elen, the bowl of Llafer’s stirred with mist,

the dogs lie low in the tufted grass and watch with pure intent,

the ragged back of the last sheep entering the stone-bound pens.

The rough ground of Wales lives in the mind for years,

springing moor grass under feet treading concrete,

hundreds of miles from home, and the ground has names,

songs full of grief, sounds that belong to a single stream,

Caseg is the place of the mare, Cwm Llafer’s the valley of speech,

utterance of wind, Fryddlas the blue moorland filled by the sky.

The farm passed down yet never possessed lives father to son,

mother to child, feeding the sheep with grass,

the people with sheep and memory with years lived looking at mountains.

One single glance of a hillside darkened by cloud

is enough to sense the world it breathes

And the names need all the breath we have:

Carnedd Llewellyn, Carnedd Dafydd, Garnedd Uchaf, all the

Carneddau, Yr Elen of the shining light, Drosgl the endless

ridge curving to nothing.

One man I know loved this place so

much he said he’d found his place to die.

Years I knew him, walking the high moor lines

or watching the coals of a winter fire in the cottage grate.

And die he did, but not before one month’s final joy

in wild creation gave him that full sight he’d glimpsed in Blake,

he too wrestled with his angel, in and out of hospital,

the white sheets and clouds unfolded

to the mountain’s bracing sense of space, now he was ready,

his heart so long at the edge of the nest shook its

wings and flew into the hills he loved.

Became the hills he loved.

Walked with an easy rest,

cradled by the faith he’d

nursed for years in doubt.

His ashes are scattered over by

Aber, the water continually saying his name,

as I still go home to Tan-y-Garth speaking the names of those I love.

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you, David. And thank you. Go well.