Some lessons take years to sink in

Before his rise to fame, David Duchovny is a popular kid – charming, funny, bright and athletic, beloved by friends and teachers alike. But there’s one teacher who puts David off-balance, calling him out for foolishness where others see charm. Years after graduation, struggling to make it as an actor in Hollywood, David finally comes to recognize that what he mistook for dislike was in fact an encouragement to go his own way, in his own time.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Some lessons take years to sink in

DAVID DUCHOVNY: In one exercise we drink an imaginary cup of coffee. For months. I feel the shape of the mug in my hands, the weight of it. I grasp the handle, and ah, there’s the heat, I can feel the heat. I smell the rich, smoky aroma of the coffee, taste it on my lips. I spend hours doing this. My Latin is pretty good, but this is all Greek to me. Acting forces me to use all of myself – not just my mind. My body, my heart. And I love it like I loved basketball and baseball. It’s not curing cancer. But it feels important. It feels good to me.

I start to realize how much energy I’ve spent keeping busy – trying to move faster than my feelings. But here they want me to slow down, to feel everything. They demand it. And I can see now how my previous academic success was also somehow performative. Posturing. But now I’m inhabiting a different, more primal – maybe even more authentic – part of myself. And so I make the call, kind of. I subtly abandon my doctoral thesis without telling anyone. And I decide to be an actor without telling anyone.

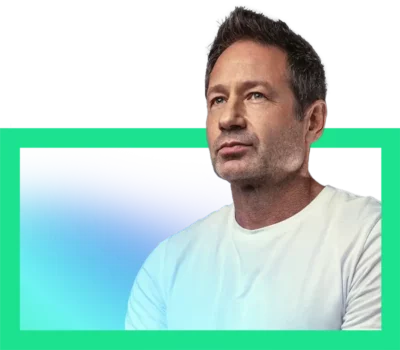

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: I grew up watching David Duchovny on TV. As a teenager in the ‘90s, his depiction of Fox Mulder in “The X Files” had a big impact on me , and made me realize that it was actually OK to think differently. Then over 20 years later, as Hank Moody in “Californication” – he won Golden Globes for both roles – I learnt even more. So it’s a real treat for me that David is today’s storyteller. As an actor, one of David’s talents is creating characters with a calm, unhurried center, despite having in his own life experienced enormous pressure and the need to move fast.

In today’s Meditative Story, David shares with us a pair of moments in his early life when keeping up a frenetic pace pushes him to the breaking point until respite comes in the form of a very special teacher.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

DUCHOVNY: It’s just me and four other boys here, bent over, working in our jackets and ties. Our desks are the old fashioned kind, with each little desktop bolted to the chair. Every time someone leans back, I hear the slow creak of metal.

We’re in AP Latin, an advanced placement class taught by Mr. Rogers on the 4th floor of what we call “the old building.” The dark marble stairs leading up to the classroom are worn to slopes on both sides, upstairs and downstairs, from generations of boys running up and down. A marker of time, like rings on a tree. This school is the oldest continually run in school in America, founded by the Dutch in what was New Amsterdam. As we wait for Mr. Rogers to get here and class to begin, we have fun translating the BeeGees current hit “More than a Woman” into Latin – plusquam femina, plusquam femina mihi – more than a woman, more than a woman to me. Mr. Rogers comes in, and we stop singing. We’re supposed to be reading Virgil’s Aeneid out loud. All of it. Books 1-6. In the original Latin, obviously.

We’ve been at it all semester. I can translate the words well enough, but I’m just not getting the rhythm. This other kid – his nickname is General Jokery – he’s not a great student, as you might guess, never does much work. But he can read this stuff. He nails the cadence. The dactylic hexameter. Arma virumque cano – I sing of the arms and the man. He just has it. And as he reads aloud, Mr. Rogers beams at him. They say Latin is a dead language and not spoken. But not to General Jokery. And not to Mr. Rogers.

I’m a successful student. I even got chicken pox over spring break in second grade and didn’t miss a day. I’ve never missed a day of school. Partly out of fear that I’ll get left behind in math or something. Or miss that one day in class where they teach us that indispensable thing I’ll need for the rest of my life, like the quadratic equation. Life would spiral downward without the Pythagorean theorem – we all know this.

But really I just prefer to be out of the house. Ever since the divorce, it feels pretty raw at home. Quiet, like a mausoleum. No music, not much laughter. And I don’t want to deal. So my way of dealing is being a great student and a great athlete – busy, busy, busy. I gotta be out of the house. AP English, history, and Latin. Captain of the basketball and baseball teams.

One day, I’m in Mr. Roger’s office, going over some work with him. He knows I’ve only taken his class so I can get the college credit. I’m not in love with Latin. And I don’t hear its music like General Jokery. He’s talking and I’m nodding, and he says, “You’re nodding at me, but I don’t know that you’re listening to me.” When he looks at me, it’s like, “You think you’re fooling everybody. But you’re not fooling me.”

There are rumors he’s a leather queen down in the Village. Apocryphal? Who knows? We don’t really know what that means, but we have an idea, so this makes him a mystery and vaguely exotic, even dangerous. Leather.

He’s got red hair heavily flecked with gray. A thick reddish-gray mustache. He wears a rust colored corduroy jacket, wool ties that square off at the bottom. Average height, trim. I can see the square heels of his boots as he leans back with his feet up on the desk.

You might think he’s relaxed. But I know better. He has a laugh like a dog’s bark, so sudden it seems to surprise even him. When it comes out, it’s as unexpected as his temper.

I can’t figure him out at all. He has me totally off-balance. I can’t psych him out. I can’t charm him. I can’t outwork him. Most of my teachers love me. But Mr. Rogers is tough on me.

He sees right through my working to please others. Most of my teachers call me “Duke.” He doesn’t play that game, he calls me David.

GUNATILLAKE: It’s well known in the meditation world, especially in Zen, that the best teachers can be the most surprising. You don’t always need to be soft and gentle to show love to others or ourselves. Sometimes it takes real personality to help point out the parts of us we avoid or ignore.

DUCHOVNY: One day, I’m in a bit of an extra hurry. It’s the middle of basketball season. I have a game that afternoon. We’re really good, we’ve only lost one game all year. I’m passing through the wide hallway that connects “the old building” to “the new building.” My European History teacher is absent today, so class is canceled, and I’m going to the 6th floor library to study.

As I round the corner, I see the elevator doors about to close, so I run. My backpack bangs against my shoulder. The doors start to close. I stick my arm in the gap between them, to trigger them to open. But the door shuts on me.

I try to get my arm out from between the doors, but I can’t. It’s just stuck there for what seems like minutes. I start to panic. Is the elevator going to go up and take my arm off? My arm is still inside it, and it hurts. But the doors eventually open, my arm comes free, and I’m safe inside the elevator.

But I’m breathing fast, from running, and from fear I might lose my arm.My book bag drops from my shoulder to the elevator floor. And when I lean over to get it, everything goes suddenly dark.

When I come to, the first thing I think is, “Oh, I’m late for school.” And then: “No, I’m pretty sure I went to school this morning.” And then I open my eyes and spit out a huge mouthful of blood.

I’m dragged from the elevator by my feet, into the library. Still not sure what’s going on. The librarian flits in with paper towels, admonishing me not to spit blood on the rug. I see another kid, a friend of mine, Bradley. His dad’s a dentist. I tell him as I spit another mouthful of blood and teeth, “I think I’m going to need your father.”

My close friends have been alerted. They keep me company in the nurse’s office, we’re laughing. My mother, who teaches at another school not far from here, eventually arrives. My friends scatter like cockroaches when she appears. Horrified, my mother cries, “What did you do to my beautiful teeth?” So now I start crying because I’ve ruined my mother’s teeth. I mean, she made those for me.

But my teeth are really the least of it. The school’s worried there’s something actually wrong with me, like maybe I’ve had a heart attack, or a stroke. So they call for an ambulance.

I spend three sleepless days in intensive care. My face and lips are completely swollen and cut, and my back hurts. I miss my friends, I miss basketball. I’m eager to get back to school.

On my third morning in the hospital, in walks Mr. Rogers, the Latin teacher. He is literally the last person I expect a visit from. Most everyone else at school assumed I’d be OK, I guess. But here he is.

He pulls up a chair and sits by my bed. His grayish-red hair is parted to the side, 70s style. I figure he’s thinking, “Wow, have you messed up. Look at you, in that bed – not very Roman.” But that’s not what he says, and he’s looking at me with genuine concern, a softer look than I’ve ever seen from him.

What he says is, “You know, you don’t have to come back.”

What I think is – what? I have no idea what he means, so I just nod. Once again, I’m nodding, but I don’t understand.

So he goes on. “Your coaches and your teachers, they’re all going to want you to come back as soon as you can, but you don’t have to. You can take your time.”

Take my time? That’s the last thing I’m going to do. I’m going to get back there as soon as I can. But I don’t say that to him. I just keep nodding.

I’m back on the basketball court by the end of the week. The doctors find nothing wrong with my heart or my head. My mom blames it all on the fact that I hadn’t eaten breakfast. So every day for the rest of my senior year, I wake up to the biggest omelet on my plate, and whether I’m hungry or not, she will stare at me until I eat it.

I finish the year strong, get into the Ivy League university I want, get some decent fake teeth, and I never faint again.

It’s a cold spring day in Princeton, my freshman year of college. And I’m surprised to see Mr. Rogers approaching the ballfield. It’s the end of practice, and we’re just working on drills for skills – bunting, pick offs – the sound of wooden bats and the ball popping in a leather glove like music. I don’t know how he found me. The baseball field is a walk from the middle of campus. To find it, you really have to know where you’re going – and want to be going there.

Maybe he’s had some business with the school, but I can’t imagine what.

We sit on these cold cement bleachers and talk. It’s awkward. He’s not an easy guy for me to spend time with. The conversation doesn’t flow, and we don’t really have a history. I’m a little embarrassed to be sitting here in a baseball uniform. Like he’ll think it’s silly that in this brand new chapter of my life as an adult, I’m still playing a kid’s game. I know he thinks sports are silly. But apparently he just wants to say hi, check in on me. Which is disarming.

We don’t discuss anything of substance that I can remember. And after he leaves, I don’t think of him again for a long time.

I’m on the path to becoming an academic, on schedule and according to plan. But whose plan?

I graduate from Princeton, and go on to grad school at Yale, where I work toward a PhD. in literature. But I need to make $3,000 this summer. I set out to get a bartending job when a friend of mine, an actor, says, “You know, if you book a commercial, you can make that much money in one day.

Now that sounds good to me. So I’m like, “I’m in. How do I do that?”

He introduces me to his agent, who agrees to send me out for commercial auditions. But if I want any theatrical auditions, she says, I’ll need to take classes.

Acting class is a revelation for me. They ask us to do things I’ve spent my whole life trying not to do: Crying. Yelling. Being loud. Losing control of my emotions. Not following rules. They want all that here. And there’s no repercussions like in the real world. No one cries if I yell, no one dies if I act the fool.

In one exercise we drink an imaginary cup of coffee. For months. I feel the shape of the mug in my hands, the weight of it. I grasp the handle, and ah, there’s the heat, I can feel the heat. I smell the rich, smoky aroma of the coffee, taste it on my lips. I spend hours doing this. My Latin is pretty good, but this is all Greek to me.

Acting forces me to use all of myself – not just my mind. My body, my heart. And I love it like I love basketball and baseball. It’s not curing cancer. But it feels important. It feels good to me.

I start to realize how much energy I’ve spent keeping busy – trying to move faster than my feelings. But here they want me to slow down, to feel everything. They demand it. And I can see now how my previous academic success was also somehow performative. Posturing. But now I’m inhabiting a different, more primal – maybe even more authentic – part of myself.

And so I make the call, kind of. I subtly abandon my doctoral thesis without telling anyone. And I decide to be an actor. Without telling anyone. Whatever that means to a 26-year old grad student.

I’m in Santa Monica, living in a tiny one-room sublet. I cook on a hot plate and do my dishes in the tub. I sleep on an odd, circular couch-bed. I love this ratty apartment. It’s four blocks from the beach and has nice little French windows, and the weather is always good for this city boy. It’s LA.

I’m not having much success. Most people don’t. But I’m not used to that. I feel like an abject failure. I have no job. I have no money. I have the flu. I’m weak, almost delirious. Raw. I fall to my knees and start crying. The word that comes to me is “Help.” I don’t know who I’m asking help from. I just know I need it.

And in that moment, I think about Mr. Rogers. When he said I didn’t have to come back. And I think I finally understand what he meant by it.

“You can take your time.”

I’ve been running this race based on other people’s expectations, performing for other people. But I haven’t defined my own measure of success. Afraid of maybe what my mom will say about being a superficial actor. Of winding up in the gutter. Which is what I’ve always thought happens when you don’t get those degrees – when you don’t get all A’s, and don’t attend every class. It’s like I’m back in AP Latin, envious of General Jokery who had rhythm, reciting Virgil with perfect rhythm.

Mr. Rogers had seen that about me. How much I needed approval, the pat on my head. That’s the quality he was speaking to when he was so hard on me. At least, that’s what I think he meant. I thought he just didn’t like me. But now, I think he might have been concerned for me.

And I’m still so needy for approval. Only instead of A’s, it means getting jobs and good reviews. But Mr. Rogers was trying to tell me: just be on your time. No amount of approval, grades, money, or notoriety is ever going to fill that. If that’s your motivation, you’re never going to get where you want to go. There’s no end to that. It’s nowhere. And you can’t get nowhere.

I think, “Wow. That’s a real teacher.” He tried sharing that lesson with me so many years ago. But I wasn’t ready to get it. And now I am. And I want to say thank you.

So I resolve to see him next time I’m in NYC, to thank him. This is before the internet, and a teacher/leather queen must be pretty good at covering tracks and guarding privacy. He no longer teaches; he’s retired, I’m told. Eventually I learn, from General Jokery of all people, that he died of AIDS a few years earlier. And I feel a great loss. I can’t tell him, “Hey, 10 years ago you sat by my hospital bed when I was 17 and said, ‘take your time.’ Well, I’m finally taking my time – or trying to. And I understand now. I get it.”

GUNATILLAKE: If you could say go and something to the “you” of 10 years ago, what would it be? And how do you think the younger you would have taken it? I’m not sure I’d have taken my advice to be honest, how about you?

DUCHOVNY: They say when the student is ready, the master will appear. But I’m not sure that’s always true. It seems to me that when the student is ready, the master is sometimes long gone.

I don’t know what Mr. Rogers would make of my career, or what he would have said to me if I thanked him. He might have told me to bug off, but I don’t think so. I think he might’ve barked a laugh at me.

I don’t think it matters. The bottom line is that he let me know that he saw something in me, and he tried to help. God, if we could do that for one another more often.

My son is applying to colleges now. He’s writing all these essays. Personal essays. And I catch myself wondering, why do we make them do this? We ask these kids to write as if they’re the people they’re going to be. They don’t know who they’re going to be yet. All I want to do is grab him from school and just go on a road trip. Say, “Forget all that, buddy. You don’t have to go back. Take your time.”

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Take your time. So, with Mr Rogers in mind, let’s take our time to settle into our short meditation together. And breathe like you have nowhere to go. Letting your breath be how it is. And your belly be comfortable.

Letting it hang out. No-one judging you. Enjoying the belly breathing. The belly taking its time, being itself.

Breathing a bit more fully if that feels OK. The pace of your breath, its depth an indicator of how you’re taking your time. No rush. Just this.

Take your time. Wherever you are in your day, at the beginning, at the end, or somewhere in between. There will be part of the mind, the planning mind, thinking about what’s going to happen next, what we need to do. It might be a full blown thought, or just a little movement of the mind, non-verbal, subtle.

Take your time. Breathe steady, breathe long. And let go of the need to worry about what’s next. Enjoying instead just this. And the echoes of David’s story through your being.

Take your time.

So, as we close, you know I realize now that while David didn’t get the chance to thank Mr. Rogers while alive, his sharing this story is such a wonderful way to do it in a different way. So my invitation to you is to think of a teacher or someone else who showed you something that made a difference to your life and understanding as Mr. Rogers did to David and say thank you. Name them silently and offer them your thanks.

Take your time to think of who it will be.

For me, it was a school teacher – Mr. Keyte – who spotted my early interest in why people and cultures do what they do and shared some books with me that ignited a curiosity that probably set me on the path that ends up with me here with you.

So, who is it for you?

Bring them to mind.

And with as much of your being as you can, say thank you. Whisper it if you like. Thank you.

Thank you, David. And thank you. Who knows, you’ll probably be a Mr. Rogers to a David one day, if you haven’t been already.