The heart comes out at night

As a Night Minister with San Francisco Night Ministry, Rev. Monique Ortiz walks the dark streets of a beautiful and aching city – a city that transforms completely when the sun goes down. Reaching out to the most desperate souls, she learns to help in a way she hadn’t imagined.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

The heart comes out at night

REV. MONIQUE ORTIZ: My nights are hard and cold. But more and more, I feel alive with everyone who approaches me: the people at the donut shops, the police officers, the Lyft drivers on a break. Sometimes spending a few hours, or even a few minutes with them – it’s a matter of life and death, just stopping, just listening.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: For over five decades, every single evening between the lonesome, strange, and sometimes mystical hours of 10 and 4, the clergy members of the San Francisco Night Ministry walk the streets of the City by the Bay. Their job isn’t to proselytize, or feed the hungry. They’re there to offer something even more fundamental – though for Rev. Monique Ortiz, it takes a while before she realizes what.

In this episode of Meditative Story, Rev. Monique leads us through a side of the city most will never know. Over the years, logging thousands of wet, hilly miles, she develops relationships unlike any she has in daylight hours – relationships with people in desperate straits and arguably a new relationship with her own soul as well.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

ORTIZ: I’m walking. Down Mission Street, left on 16th. It’s one of those still nights, where you can hear the street lights click from red to green. Foil from a burrito skitters along a shuttered pawnshop. Earlier in the night, this part of San Francisco is 1,000 volts of electricity. Bars, bands, parties, skateboarders bombing by periodically, couples squabbling then making out in the park up the street. But then the last train whinnies away. Bar doors swing open then shut, and the 20-somethings drift home. I feel the wind push in from the Pacific a few miles west with its edge-of-the-country loneliness. I pull my coat tighter. December in San Francisco is wet and cold in a way that reaches deep into your bones.

I’m walking. Right from 16th onto Capp Street. The 14 groans past, opens its doors with a sigh, groans on. I see a pair of pigeons hunching against the chill beside an old sneaker. The cheap hotels and palm trees and old Victorians are silhouetted against the black sky. I keep walking. This, for the next decade, between the desperate and sometimes miraculous hours of 10 p.m. and 4 a.m., is my job.

I am a Night Minister. In 1964 the first of my kind starts strolling the streets of the city, offering something different than charity workers – at a time of day when the world is extra cold, and for many, extra lonely. All churches say they’re open to everyone, but they’re not, not really. To reach the most broken souls, you have to go to them. And so, every single night since, 57 years and counting, rain or shine, the San Francisco Night Ministry has sent a roving band of clergy members out into the city’s hardest neighborhoods.

But to be honest, I’m struggling. I’ve undone everything in my life for this job, and after a few months, doubt is creeping in. The point is to make a difference. Ever since I hear my calling at the age of 10, growing up in Mexico City, helping people is my reason for being. I go into journalism, believing that would let me affect change. But gradually I see I am just reporting the same bleak stories day after day, never doing anything about them. One day I put down my microphone. Months later I enroll in divinity school. It is hard, hard work, but I make it through, all to wind up now with this sinking realization: I’m saving nobody.

Julie is in her 70s, and she has cancer. She should be somewhere safe and loving and warm. Instead she sleeps under a tarp. We’ve been talking a lot these past few weeks. Tonight she’s really sick. I give her some extra socks and offer to bring her a couple tacos, but she shakes her head. She doesn’t want to talk much. I feel useless. There’s so much suffering lately. Tech has funneled untold wealth into San Francisco, but this exacerbates the city’s horrific housing crisis, and thousands of people are shoved to the margins, to the street. Every night I meet men and women in states of despair, suffering in a way you just don’t see during the day. They walk up to me and tell me they have no idea what to do, where to go, whether to keep going. I offer an ear, offer my heart. But what can those do?

That question echoes in my ear throughout the night. Here’s a man bent over on the curb in grief of some sort, just racked with it. Another woman tells me she’s all but given up. Around 1, I find myself walking back to my van. By the time I climb into the driver’s seat, I’m sobbing.

“I’m not doing anything,” I shout into my dashboard. “I’m not helping anybody.” I can hold their hand or pray with them, but I can’t change their circumstances. I don’t even have the money to put Julie in a hotel room for a night. I must have misheard my calling. I’m surrounded by all this real pain, and there’s nothing I can do to change it.

My body shakes, my breath is ragged, fogging up the old windows of my van. Only after a few minutes do my sobs begin to subside.

It’s late one night before Christmas, and I’m in the Mission again, near the check-cashing place and the cramped little falafel shop on 16th Street. Some light decorations glow from the windows of closed storefronts. There’s a bus stop here, and I see an old man leaning over on the bench. He has a scraggly gray beard and deeply lined skin.

“Good evening,” I say. He looks up, notices my collar. Some people aren’t used to seeing a female minister. But he sits right up and goes, “Oh, hi. How are you doing?” A cane rests on the bench. He’s wearing multiple layers, topped by a worn leather jacket. He invites me to sit and talk, and quickly his story tumbles out. I learn he has late-stage liver disease. He spent 18 years living on the streets. Now he’s staying at a nearby SRO – a single room occupancy hotel – though he still comes to the benches, especially when he’s been drinking. He looks at me. “You’re not going to tell me to stop drinking, are you?” he asks.

“I’m not here for that,” I say. My father was an alcoholic. That and his belligerence split apart my family when I was young. But I am not here to judge this man. I’m not here to proselytize or convert him. I don’t blame him for his circumstances.

“Well, good,” he says, revealing a toothless grin. We hang out a while longer, and when he’s ready to head back to his hotel, I walk him back. A big, dilapidated marquee hangs over the entrance. I give him my card. He tells me his name is Ron.

The work in many ways is simple. I just walk slowly, and let people approach me, which they often do – something about the collar, or maybe my face, invites contact. Still, there are days when it also feels impossible. One night a cop pulls me over on my way home – I’m so tired it looks like I’m drunk driving. But things have also begun to shift for me a little since that night crying in my van.

Not long after meeting him, Ron shows up again, this time at our Open Cathedrals gathering. He’s grinning, draped in necklaces made of crystals and stones. We pick up where we left off. Though he looks 70, I learn he’s 49. I learn he worked long enough as a University of California janitor to have a small pension. I learn there was a bad motorcycle accident, and that he has schizophrenia. Sometimes, it’s rocky. If he’s drunk and short-tempered, I or my fellow Night Ministers will say, “I’m not going to take that, but we’ll talk another day.”

Ron keeps showing up. He becomes an usher for our gatherings, hobbling among the makeshift seats outside Civic Center. We lead utterly different lives, but a connection starts to form. I call him brother, and he calls me sister.

I haven’t mentioned yet what happens to me that night in my parked van. Yes, I cry and rail. But then I stop, and for the second time in my life, a voice from within speaks to me: “You’re not here to save anyone,” it says. “You’re only here to love them.” It washes over me. Love them. That, I think, I can do. I can’t sing. I can’t draw. I don’t have any great talents except to be out there and really love people genuinely, from any walks of life. Faith or no faith, they’re human beings, and they are beautiful, and they are precious. Mine is not a ministry of deliverance, I see, though we can help with small things like blankets and food. It’s a ministry of love.

GUNATILLAKE: You know this distinction, don’t you? The difference between wanting to fix others, and loving them just as they are. Let’s practice love like Monique. Loving whatever is happening now just as it is … especially for what it is.

ORTIZ: My nights are hard and cold. But more and more, I feel alive with everyone who approaches me: the people at the donut shops, the police officers, the Lyft drivers on a break. Sometimes spending a few hours, or even a few minutes with them – it’s a matter of life and death, just stopping, just listening.

Three years after Ron and I first meet, I’m across town at Faithful Fools, another street ministry. The upstairs room smells like tomatoes and ranch dressing. This is our Tuesday Gathering, it’s like a support group, where we sit in a circle of about 15 people. Ron is one of them, and he tells me recently that he’s dying – his liver disease will wait no more.

Usually on these Tuesday evenings we check in on each other’s lives, but tonight I have an idea.

“You guys,” I say to the gathered faces. “Ron has been open with us about his addictions and his health, and one of these days he’s not going to make it here. I want to celebrate his life tonight, while he is still around to see it.”

I look across the circle at him, his chest full of necklaces. I ask him if this is okay. He nods, his eyes serious. “Let’s do this.”

GUNATILLAKE: Let’s do this. Imagine sitting here with Ron, Monique, and the others. Bring the brightness, tenderness, and attention this moment deserves.

ORTIZ: So one by one, the Faithful Fools share what we love about Ron: his good cheer, his lovable explanations of natural history. Someone says he would always give them his last dollar, “even though he wanted it for beer,” and we laugh. Ron takes it in, crying quietly.

A few days later, my phone rings, and it’s him. “I want to live,” he says. He’s decided to try rehab.

I know I’m not here to save Ron, or any of the thousands of other men and women I meet over the years. My job – the simplest and the hardest thing about it – is to love them all, even if it doesn’t affect their outcomes. It’s a different kind of love than what we learn as children. It might not be reciprocated. I might not love their choices. But I accept them. When you don’t have that in your life, it’s very easy to give up – and for the rest of the world to give up on you.

I realize that offering something as squishy as love might seem like weak medicine. Many of the men and women I get to know are unhoused, or mentally ill. Plenty suffer terrible abuse. To be sure, they often need extremely tangible, concrete things – a roof over their heads, for starters. But over time I see that love isn’t just a sweet word you say to someone. Accepting someone for who they are is actually one of the most powerful things you can offer. It re-wires them.

Maybe it is my own difficult childhood that lets me love them like this. Maybe it’s because I still know suffering. I have my share of debilitating illnesses. We all take turns being the teacher and the student, the one who is lost and the one who is found.

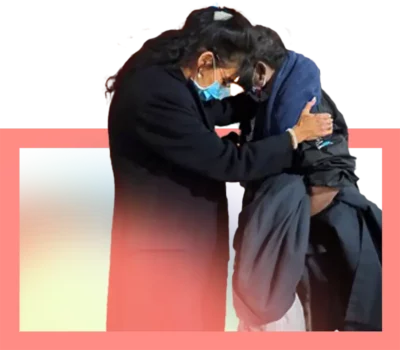

Ron enters a 30-day addiction-treatment program, then a year-long program. He stays sober and alive another five years. Then one day I get the call. He’s being admitted to hospice. It’s me they call. Among other things, Ron gives me Power of Attorney a while back. For him, like so many, we are it, we are their sole emergency contact. I ask him if it’s okay if we try to locate his mother and his sister. In his gravelly voice he says, “Yeah, Monique, I would love that.” The hospital, St. Francis, does an amazing job, and we manage to track his family down. His sister comes to visit, and just in time. Ron never makes it to hospice.

I have walked with Ron for eight years. I have seen ways that our relationship changes him, and ways it simply has given him a measure of peace in the life he chooses. I’m fine with either.

Over those years the streets only get harder. But in a way I just grow fonder of my walks – of the thousands of miles of grimy city blocks I cover. There’s magic in this city at night. The frivolousness of the busy daytime world falls away. What remains is both more intense and more peaceful – the city, distilled. I look up at the darkening sky, and I breathe in the moist air, feeling it expand into my body. I close my jacket snug around me. I take my time to love.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: There was so much wisdom in Monique’s story, both natural and hard-earned, it’s difficult to know what to add. So inspired by her practice, let’s go for a walk.

It’s way underrated, but walking meditation is, low-key, really important in the mindfulness tradition. And it’s been a massive part of my own training. It did take me a while to fall in love with it since sitting meditation gets all the good PR, but fall in love with it, I did.

So what I’m going to do is introduce three small but beautiful mindfulness techniques you can do while walking. You can just listen to them and give them a go when you’re next out. Or you can pause now, wait to go outside, and try them as you listen along. Or both. As always, it’s up to you.

I loved how Monique talked about breathing in the city air, feeling it expand in her body. For many people, feeling connected to our bodies while walking is easier than using breathing. So that’s the first walking technique we’ll try.

Just walking, and feeling the contact with the ground with each step. Noticing what walking feels like. The movement of the legs. The contact with the ground. The feeling of the air on your face.

Stepping left. Stepping right. Making contact through your feet with the earth.

Left. Right. Walking.

The mind connected in the contact of your feet on the earth as you move.

So that’s simple walking meditation. For the next technique, think again of Monique. When she walks her ministry, is she rushing around? I don’t think so! If anything she is slightly under her regular walking pace, leaving the space for seeing the people, the stories looking for connection. So let’s try that too.

Try reducing the pace of how you’re walking just a little bit. Walking just a tiny bit slower so that you know you’ve slowed down, but no-one around you would really notice.

Aaahhh. Can you notice the difference?

Notice how slowing down only a tiny bit, going down just one gear can feel so different. How do you feel now?

What do the sensations of walking feel like now? The way your feet touch the ground? How is the attention now that the body is less rushed? Are you able to notice more or less? Enjoying life at this speed.

The final walking technique is back to Monique since it’s a walking kindness meditation.

As you walk, connected to the earth. Left. Right. Left. Right. Just a tickle slower than you’d normally walk.

And now instead of putting your attention in your feet, put it, instead, in your chest, the area around your heart. Nothing more to it than that. Walking. Walking.

With the awareness centered in the chest – in and around the heart.

Letting the body be relaxed and natural. With the awareness centered in the heart.

And if you like, you can imagine that emanating from your chest is a beam.

A beam of attention. A beam of care. A beam of kindness. A beam, even, of love. All emanating from your awareness.

Walking. Present. Connected. Aware of the area of the chest and heart.

Sensitive. And beaming out kindness and care.

To everyone in front of you. To everything in front of you.

Inspired by Monique, the most heartful superhero around.

Thank you Monique and Ron. And thank you. Walk well.