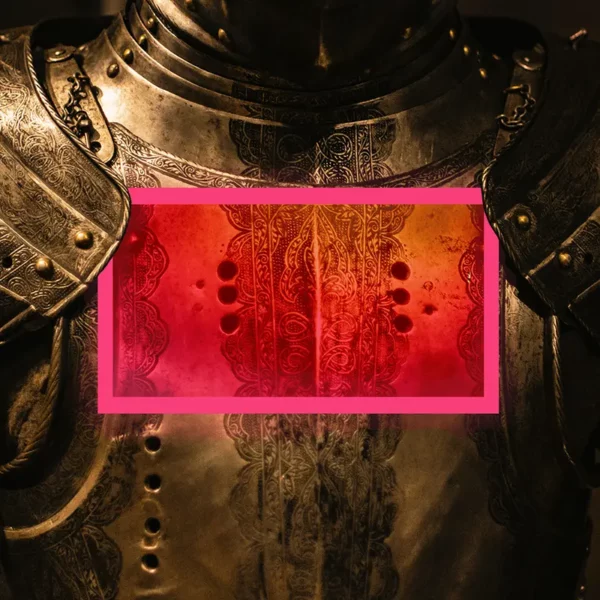

The human truth underneath our armor

Keith Ferrazzi is the author of Never Eat Alone, a classic book about working relationships. But before he became an expert on building bonds at work, Keith is busy building emotional armor around himself – to hide his background, his ambitions, even his true feelings. He shares his story of building that armor, and then slowly learning to dismantle it, piece by piece.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

The human truth underneath our armor

KEITH FERRAZZI: It’s the first time in my life I’ve removed even a piece of my carefully constructed armor. But miraculously, I don’t feel weak. I don’t feel wounded. I feel more alive than I have in … ever. I start to see how sharing vulnerability – in the right place at the right time with the right people – can actually accelerate, can actually deepen friendships, not drive them away.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Keith Ferrazzi is the author of a classic book about working relationships, called Never Eat Alone. At his company Ferrazzi Greenlight, he coaches organizations on new practices, mindsets, and behaviors to transform them from within. His latest book, Competing in the New World of Work, explores the workplace innovations that have emerged during the pandemic.

But before he became an expert on working relationships, Keith builds emotional armor around himself to hide his background, his ambitions, even his true feelings. In today’s Meditative Story, he shares his story of building that armor, and then slowly learning to dismantle it, piece by piece.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

FERRAZZI: I’m lying on the red shag carpet in my bedroom. It’s 1976, and the whole room is ready for the American Bicentennial. I’m 9 years old, I’m the grandson of immigrants, and I’m a patriot. Everything looks like a flag. The wallpaper is red, white, and blue. There’s drums and bugles. The dresser is painted blue and white. But lying there on my stomach, cheek on the carpet, I don’t see any of that.

My eyes are fixed on the rusty, metal ventilator in the wall. It’s a heating vent that starts in the basement, and runs straight up through the kitchen, to my tiny second floor bedroom. It picks up every word my parents say in the kitchen below. And they’re arguing. Again.

My father’s unemployed. He takes whatever rough side jobs anywhere he can, but it’s not enough. And it breaks his pride. My mother becomes a cleaning lady, just to make ends meet. And it breaks her spirit. The Pittsburgh steel industry – it’s crashing around us. The entire town is crashing. And my parents are arguing. We can’t afford gas to get in to town. We can’t afford to buy new clothes. Every word is loud and angry. Years later, I’ll understand the kind of pressure and despair that raises decibels that high. But to my 9-year-old ears, I’m afraid.

And my thoughts immediately race to my older sister, Karen. Gosh, I miss her so much it hurts.

I’m just three years old. And I can’t stop crying. I’m screaming her name, “Natin! Natin!.” (I can’t pronounce Karen so I call her “Natin.”) I’m screaming, “Where’s my sister? Where’s my sister?” Karen’s always been my greatest protector. She’s 13 when I’m born. Her mother has remarried, and I’m the child of that new marriage.

Karen is beautiful and fun. She’s everything to me: she’s life, she’s love, she’s vitality. But she’s also in constant conflict with her step-father, who’s my Dad. In my Dad’s mind, he’s just trying to bring discipline and order to Karen and my step-brother. In Karen’s mind, it’s a horrible place to be. All of this tumult, this anger, this resistance – it leaves Karen also feeling fear. This new baby – me – this gives her a place to feel loving and loved. For me, sanctuary is in my sister’s arms.

Karen gets pregnant, leaves the house and gets married when she’s only 17, and I’m 3. My very first memory is crying for her.

Lying here on the red shag carpet, my parents are still arguing downstairs. I hear their anger, and yes, I hear their fear. Without Karen, I feel so unprotected. I decide that I have to look out for myself, because nobody else will. I can’t see how much they care about me, how hard they fight for me. And right here, on the red shag carpet, I start to put on the armor. It will take me a lifetime to disassemble.

I hear the little bells jingle as the door swings open. Someone else walks into the “Nearly New” shop, in Ligonier, Pennsylvania – the place we go to buy cheap used clothing. I duck behind a rack of used blazers. The musty smell hits my nose. I peer around the scratchy wool jackets, and I see a boy I know from school. His mom sets down a big armful of clothes on the counter.

My face feels hot, my forearms itch, and I can hear my heart beating loud in my ears. But I don’t move an inch.

They’re here to donate the stuff that I’m here to shop for.

I ask my Mom if we can get out of here before someone sees me. Her face is taut, but her eyes are gentle around the edges. She heads toward the counter with two beat-up, branded, Izod shirts at throw-away prices and one slightly-too-large jacket with holes in the elbows.

My Dad gets me into the richest private school you can possibly imagine. I get a full scholarship, but we can’t afford the school uniform. So Mom takes the Izod labels off these old shirts and sews them onto the new polo shirts she buys cheap from K-Mart. She also sews elbow patches over the holes in the jacket.

These clothes are an attempt for me to fit in, to look the part. But it couldn’t be clearer: I just don’t belong. And I can’t let the other kids find out. I can’t let them see me for who I really am – who my family really is. Along with these clothes, I wrap more armor around me.

People put on armor of all sorts. There’s armor that’s introversion. There’s armor that’s being a jerk. There’s armor that’s being smarter and richer than everyone. My armor is charisma. I have my father’s gift of gab, and I learn to talk to people. I learn to make them laugh. I learn to entertain. I learn to go big. And most of all, I learn to look the part.

Karen leaves the house when I’m three, but in truth she doesn’t move far. I see her on Sundays, holidays, and birthdays, but every time we’re together, it feels like a birthday. There are games. There’s silliness. We put on hats and costumes. But most importantly, I always feel with Karen, like I belong. Like I matter. Like I’m enough.

I’m standing behind the curtain on a small stage, in a small restaurant. I’m 16, and I’m playing Don Quixote’s right hand Sancho in a local dinner theater’s performance of Man of La Mancha. My costume is a pillow stuffed under my shirt. As I look out from behind the curtain, there’s probably a half dozen people in the audience. And one of them is Karen — smiling, waving, applauding. She comes to that terrible show more than once. Just knowing that she is in the audience, I just want to make her proud. But that’s the thing with Karen: I don’t have to do anything to make her proud. Just being me is enough for her.

As the absolute poorest kid at a very rich school, I learn how to talk like other kids. I drop my Southwestern Pennsylvania blue-collar accent. I never say “ain’t” anymore, and I’ve started saying “downtown” rather than “dintin.” I don’t tell people my dad is a former steel worker. I now say, dad’s “in manufacturing.”

At my first dance, the boys who belong at the Rolling Rock Country Club, they wear classic herringbone Blazers. I’ve never been to a dance before, so I go out, and I buy a ’70s-era leisure suit. When I show up, they think it’s a costume. A girl at the dance nicknames me “Polyester Palace.” So, on the outside, I get big. I play into the nickname. I embody the trend-setter with a sense of style the others just haven’t caught up with.

But inside, I feel a constant sense of shame. The other kids don’t think I deserve to be there – and, you know what, they’re absolutely right. I’m poor. They’re better than I am. But I’m going to achieve. I’m going to work harder. And someday, I’ll join that country club. Someday, I’ll be as wealthy as they are. Someday.

The closer I get to fitting in, the more my parents stick out. The way they talk. The way they dress. My parents see it too. My dad often shows me his hands, and he says, “I don’t want you to have to work this hard.” They’re always weathered and dirty. He can’t even scrub out the dirt in the crevices, even with gasoline.

He wants something different for me. He thinks I can achieve the greatest things in the world. He thinks I can be President of the United States. Isn’t this what immigrant families do for their kids?

One day, Dad picks me up from school in our beat-up green Nova, with rust spots all over it. Everyone else gets picked up in a chauffeured car. I get in, I look down, as I always do, so I don’t have to make eye contact with anyone while I’m sitting in this junker.

As we pull away from school, I feel this rush of shame. I can’t hold it in anymore. I say, “Dad, would you please wear a suit next time you pick me up instead of your work clothes?”

He’s silent for a few seconds, and then he explodes. He stares straight ahead, and he just yells at me. I can feel his sense of betrayal, the hurt behind his anger. But I’m too ashamed to care, and I explode right back. I learned my anger from him, but he’s never seen me like this before.

By the time we get home, we’ve both gone quiet. He drives in silence while I stare out the side window. When he turns off the car, I walk inside, I go directly up to my room, and I don’t come down until morning. That night, I divorce myself from my parents. I understand they’re doing their best, but they can’t help me. That’s what I think to myself. And in my mind, I put on one more layer of armor – between myself and my classmates, between myself and my parents, between myself and the world. I have to completely conceal the old me – the poor me – so that no one will ever know.

GUNATILLAKE: Layers of armor in Keith. And layers of judgment – perhaps in us as we listen. Are you able to notice any judgments that are here for you, in response to Keith’s words so far? As his story continues, be interested in how your inner commentary cements its position or if it changes.

FERRAZZI: In college, I master the art of becoming someone else. I change the pronunciation of my name from Ferrazzi to Ferrazzi. It sounds more sophisticated. I wear bow ties and suspenders. I bust my butt working side jobs, so I can spend a lot of money. I over-spend, so everyone will assume I’m rich. Some people’s armor makes them small, so that they can hide themselves. Me? I choose to get big, bold, and ambitious.

No one here knows anything about my past – and that’s exactly how I like it. Until one day, I get a glimpse of a very different way.

It’s my senior year, and I’m sitting on the floor of an elegant living room – a crackling fireplace off to the side, gothic ceilings overhead. I’m in a secret society at Yale, and there are a dozen people my age. We’re all sitting cross-legged, in a circle, gathered for one of the most beautiful rituals of the society.

Over the course of the year, everyone gets to tell their story for an entire evening. A full night devoted just to you – two-to-three hours straight. And the goal is to share everything. The arc of your life. Your deepest, darkest secrets. Your greatest struggles.

I hear my friends reveal abuse and alcoholism and deep insecurities. I notice how these shares bond us together, instead of what I would have assumed, which is repelling us from each other. I feel how the group embraces people for the secrets they share, instead of judging them. And it’s kind of amazing. Here – with the smartest, most confident, most successful people I’ve ever met – vulnerability brings us closer. It’s the exact opposite of everything I’ve believed. Everything that I’ve armored myself against.

Tonight is my night. I’m prepared. I’m generally good at public speaking. Still, it’s hard to begin. I feel so afraid. My stomach aches. My mouth is dry. I’m not used to telling the truth about myself.

I look around the circle at everyone’s face. I rub the sweat off my hands into a Persian rug that’s probably hundreds of years old. I’m scared and already ashamed of what I’m about to share. But I’m eager, too. I want to be known.

I tell my whole senior society about how I grew up poor. About blue-collar life in Southwestern Pennsylvania. About the beat-up green Nova and the polyester leisure suit and how my dad isn’t really “in manufacturing.”

I break down, several times, shame running down my face in tears.

After, I feel raw and I feel exposed. It’s the first time in my life I’ve removed even a piece of my carefully constructed armor. But miraculously, I don’t feel weak. I don’t feel wounded. I feel more alive than I have in … ever. I start to see how sharing vulnerability – in the right place at the right time with the right people – can actually accelerate, can actually deepen friendships, not drive them away.

But there’s a deep, burning sense of shame that still remains. Because even though I open up more than ever before, there’s a darker secret that I couldn’t share. Even in the warmest possible environment I’d ever been in.

I first become aware of my sexuality in fifth grade. It’s when I realize that I had feelings for boys in my class. Feelings that are different from what I thought they should be. Even now, in college, I don’t see any way for that to be a part of my identity. This is the 1980s, and I don’t see a single gay role model for the kind of person I want to be in the world. The TV show Will and Grace is still a decade away. Even Liberace is pretending to be straight at this time.

Look, I’m a practicing Christian. I want to be governor of Pennsylvania. I want to be president one day, just like my parents dreamed. If I share that part of myself, there’s simply no path between me and my future.

So, as I shed one layer of my psychological armor, I reinforce another. No one can know I’m gay. I resign myself to living a double life. I’ll marry a woman and I’ll have children, if that’s what it takes.

I’m sitting in the living room of my home – newly painted. I’m 22 years old. I’m living in Philadelphia, and I’ve grown close to an Episcopalian priest and his wife. I sense the openness in his heart, and one night, I gain the courage to confess my sexuality to him. My entire life, I’ve learned in the church that homosexuality is a sin. It’s a deep burning shame. Something to hide. Something to repent. But his response is amazing. He received my words better than I could have dreamed, with full, unequivocal acceptance — acceptance for who I am and what I am. He tells me, I’m okay. No, he tells me I’m wonderful. That I don’t need to change.

Coming out to him is such a powerful feeling, and such a scary feeling. I can glimpse now how it feels to live without armor. And I feel forced to make a choice. I can stay on my political path, and live my life in the shadows — hiding, dodging, marrying a partner who I don’t love in a way that I want to love a partner. Or I can live authentically as myself, which I believe means dropping my ambitions in politics completely.

I do change the course of my life. I’m still not out to almost anyone at this time, but I’m out to myself — and to my boyfriend, who everyone else thinks is just my roommate. When we have dinner with the priest and his wife, it’s the first time anyone treats us as a couple.

It will be many years before I’m public about my sexuality. But in that living room, with that extraordinary human, I learn, again, that sharing the most vulnerable parts of myself makes me stronger, not weaker. I change my career, and slowly, slowly, I change how I lead and how I live. I see the incredible power of vulnerability to connect me with others. And that connectedness, that sense of belonging, that’s what I’ve always wanted.

GUNATILLAKE: There is a real beauty here, a real release. Let’s enjoy it. Breathing where you are, turn your mind towards that which is here, and which is lovely.

FERRAZZI: Decades later, I’m shocked when I hear my sister Karen has been hospitalized. The doctors tell me that she has less than one year to live. But she ends up living for three more years. And those three years mirror our first three years together.

I spend so much of my life feeling that I have to take care of myself. But caring for my sister, I feel more deeply focused on another human being than I have ever in my life. For those three years, it’s all about her. I’m relentless in seeking medical solutions. She goes from the brink of death to full recovery. But then cancer comes for her. And despite everything we do, she takes a turn for the worse, and we lose her.

I’m crushed. I miss her immediately, and without end. I feel like that 10-year-old with his cheek on the red shag carpet. I feel like the 3-year-old crying for my sister.

But as I grieve, I realize that caring for her… it changes me too.

After Karen passes, I sit on a seat in her home and I flip through her scrapbooks. They’re meticulously filled with photos, letters, ribbons. I turn a page and I see the faded ticket for my production of “Man of La Mancha.” In an instant, I’m 16 again. But I’m seeing the show through grown-up eyes. With my sister, I can just be myself, with a pillow under my shirt playing a goofy character in front of a handful of audience members eating chicken parm as they watch. That’s enough for her. That’s beautiful to her.

In every memory of my sister, I feel safe and accepted. And I can see now that safety and acceptance… it’s always available to me. It was there for me when my sister held me as a toddler. And it was underneath my parents’ arguments with each other. It was there in their love and support of me, even though I couldn’t see it at the time.

So many of us wrap ourselves in armor that we just don’t need. We contort our lives, our emotions, our feelings, to adapt to not having enough. But the reality is, that more than enough is available. There’s love and comfort and support around us already. It’s always been there.

Underneath every suit of armor is insecurity and fear – and also, intimate, beautiful, human truth. Carrying armor is painful and it’s cumbersome. It slows us down from the freedom and the flight and the possibility and the lightness that exists all around us. But anyone who has lived inside a suit of armor knows, the armor doesn’t come off easy. And in fact, it might never come off completely.

I build my life now around rituals that help me and my friends and my family and my colleagues share these vulnerable truths, big and small. But I still spend part of my time armored.

I remind myself: My sister had had the answer all along. I don’t need the achievement or the acclaim or the accomplishment. What I need – what we all need – is to trust that our vulnerability invites others to remove their armor. And when that happens, life bursts through, when we allow those around us to see that our humanness lies underneath. Humanness, fully exposed, this is the source of connection and love to each other. And that’s the safest place of all.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Keith.

Now as you might know, each week I invite you to join me in a meditation woven from the threads that most strike me from the story.

And today I hold two threads: armor in one hand and vulnerability in the other. And where they’ll meet is in a much loved technique called a body scan.

This works best if you are sitting or lying down and are able to dedicate yourself to the meditation without any other distractions or duties.

Ok… this armor thing. We all have it in our own way. And often, it’s useful. But just as often, we can forget it’s there. A good example of a kind of armor like that is tension in the body. Things happen throughout our day, which put us on alert, which leads us to holding, as a defense mechanism of sorts. So what we’ll look to do is move our attention down through the body and invite any armor that is here to soften.

So starting in the head. Eyes open or eyes closed, whatever feels best and safest.

Is there any holding here? Maybe in the jaw or eyes. If there is, notice it. Thank it for protecting you, and invite it to soften.

Now, slowly, at your own pace really, dropping down into the neck and shoulders — a classic place of armor. Wow, I can really feel mine here. And just feeling it makes it drop down. What’s it like for you? We know that there’s armor here if we can feel tension. Thank you, but it’s ok, the armor can be let go.

Now, the chest. Imagining a suit of armor, and this is an important piece, covering your heart and other vital organs. What holding or tension is here? Thank it. Invite it to soften.

The upper and lower back. The belly. Interested in this whole area, traditional places for us to have armor, in all senses. Knowing it. Inviting it to soften. And no big deal if it doesn’t. It’s the invitation that matters, not the result.

Now the hands. They literally hold so much during the day. And there can be armor here, our hands in gauntlets. Invite your hands to let go of their armor. It’ll be ok.

And the lower body. Noticing any holding. Thanking. Inviting. Releasing.

I love the bit in Keith’s story when he’s at his college society meeting, everyone cross-legged on the floor, and he’s sharing his story. His friends around him in a circle, literally making the space safe for him to be open and vulnerable. And he is. So much.

In the spirit of that vulnerability, and with our own armor now a little bit looser, we’re going to slowly scan back up from your feet to your head.

Take as long as you feel you need to. And as you do, feel what tenderness is here. I’d suggest you be especially aware of the front of the body, where we tend to be most guarded.

Our belly, our chest, the neck, the face.

Part of the reason we put our armor on, the reason it arises, is because the outside world can be a lot. But another part of the reason is often that we just aren’t quite ready to feel what is here in the front of the body, the heart area, the gut — our centers of emotion and feeling.

So let’s do that.

Feel what is here under any armor that may have softened. There is a lot of tenderness in my chest as I record this. What is here for you?

For many of us, the journey towards healing is one of recognizing armor, learning how to put it down, and noticing what freedom can arise when it’s no longer there. And there are also times when we need it, so there’s a real skill in putting it back on on-demand, rather than it being there by default.

Thank you Keith, and thank you.

We hope you’re safe and well.