To become a whole human, never stop learning

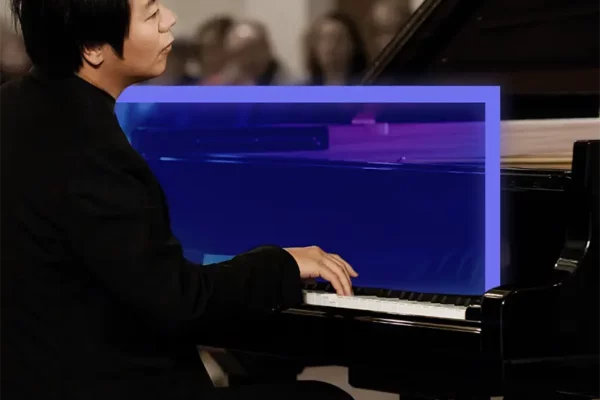

Considered a prodigy in China, Lang Lang arrives to the U.S. certain of what it takes to be the best pianist in the world – dedication, discipline, hours of solitary practice. But when a legendary teacher poses an unexpected question, Lang Lang comes to understand that becoming a true musician will require more than hard work – that it’s not so much what he puts out that matters most, but what he takes in: new music, languages, art, literature, foods, and friends. As Lang Lang’s world expands, his ambitions move away from seeking fame alone to becoming an infinite student infinitely learning, eventually connecting him even more deeply with his own culture – and, ultimately, with himself. Photo credit: Olaf Heine, courtesy of Deutsche Grammophon.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

To become a whole human, never stop learning

LANG LANG: The first time I step into his home, I stare wide-eyed. It feels like a museum. The whole place smells like history: rich, earthy, full of meaning. I was born and raised in China, but this art is unlike anything I’ve seen before.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: When it comes to superstars in classical music, it’s hard to think of anyone bigger than Lang Lang. The first Chinese pianist to be engaged by the Vienna, Berlin, and the New York Philharmonic orchestras, Lang Lang is known for his extraordinary talent and captivating performance style. And in today’s Meditative Story, Lang Lang takes us to the time when he was newly arrived in Philadelphia from China and how his first teacher there opened his eyes to what it meant to be a true musician.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide. The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

LANG LANG: Somehow it’s snowing in Philadelphia, even though it’s March. It’s my first time in America. I’m 14. I walk into the ground floor office at the Curtis School of Music, where I’ve been invited to audition by Gary Graffman himself. In the world of classical music, Gary Graffman is a legend.

I’ve never been more nervous in my life. My communication skills aren’t great. My English is very poor. I have only the most basic grasp on the language. I fear that if I don’t get into Curtis, I will never be a great musician.

As soon as I step into his office, my expectations are upended, because he greets me in Mandarin, not English. I am shocked. After a brief introduction he asks me, “Can you play a piece by Beethoven?”

I’ve performed Beethoven countless times before – for teachers, for judges, even for audiences. But I am terrified. I entered my first national competition when I was 7. Not only didn’t I win, I was not even top six. Not even top 10. Losing that competition completely destroyed my confidence. But I went home and worked hard, because I know there was another competition coming up. There is always another competition. But If I fail today, I will not have another chance to work with Gary.

I sit at the piano in his office. My fingers fall on the keys, and I start to play. The force required to press the keys is something I don’t expect. These are the heaviest piano keys I have ever come across.

Once my performance is over, Gary sits down with me. After a brief silence he asks, again in Mandarin, “So what do you like to do?”

I blurt out: “I’d like to study with you because you’re a great teacher. I want to know how to be the most successful pianist in the world.”

He looks at me for a moment and pauses. “No,” he says. “Don’t think about how far the music can take you, or what music can do for your career. What can music do for you, as a person? How can music change your life, make you better? What if you stopped trying to become a famous pianist and started thinking about becoming a true musician?”

I am confused. Until now I’ve trained on the piano like a professional athlete trains at their sport. Rigid. Regimented. I am extremely competitive. Being the best is the most important thing in my life. It has driven me since I was a child.

“Fame,” he says, “can last for a very short time. It may last for just five days. If you don’t take this opportunity to improve yourself personally and artistically you’re missing out on an opportunity to change your life.”

What is he talking about?, I wonder. Is he going to put me in a dark room to just practice all the time and not give me the opportunity to shine on stage? I look around his office and see a lot of books on his shelves. He’s an academic. Does he believe my path is to become a great academic?

Even in Mandarin I don’t understand what he is saying to me. A “true musician.” What does that even mean?

GUNATILLAKE: Can you imagine the young Lang Lang here, sitting with his teacher, confused yet curious? As you listen, can you bring some of that curiosity into how you are? Embody it. Spine alert, chin lifted, mind relaxed.

LANG LANG: Gary invites me to New York for private piano lessons at his apartment. I take the bus from Philadelphia, then get on the subway and head to Gary’s building. The journey takes a few hours each way – a journey I will repeat every other Saturday morning.

There is no TV, and the space is filled with Chinese antiques.

The first time I step into his home, I stare wide-eyed. It feels like a museum. The whole place smells like history: rich, earthy, full of meaning. Next to the sofa there are ceramic pigs, chickens, other animals, like a little Han Dynasty farm. On the fireplace mantle, a Ming vase. Across the room from the front door are bronze statues of horses. Chinese watercolors hang from the walls – famous images of Chinese women, heavyset figures, a classical motif, beauty in its ideal form for the time. I was born and raised in China, but this art is unlike anything I’ve seen before.

I’ve been in America for a few months. Culturally everything feels so different. But Gary’s appreciation and love for Chinese culture and language sets me at ease. In many ways he understands where I come from even more than I do. So this space, his home, it feels safe to me – it feels like a sanctuary.

Gary and his wife, Naomi, welcome me with such warmth. Naomi is a great dessert chef, she bakes me brownies and serves me tea – but not Chinese tea. English tea. Gary proudly shows off his vodka bar, a symbol of his Russian heritage.

As they walk me through the apartment, Gary points to the different pieces in his art collection, and tells me the stories behind them – how he acquired them, the histories that inform them, their significance as symbols. And I begin to notice what he said on our first meeting, that being a great musician requires more than a focus on music alone, but an immersion in art. Not just the art of classical music, but world art.

In the middle of Gary’s living room are two grand pianos.

After our first lesson he informs me that I’m to learn a challenging new piano concerto each week. When I pause to look up from the keys, I see Carnegie Hall across the street, framed by the window – it excites me, and it taunts me. I stare at it in awe. It’s exactly where I want to be. And it’s right there, almost within reach.

GUNATILLAKE: Again, let’s sit with Lang Lang, this time as he dreams of performing in Carnegie Hall. Here on the piano stool working hard, but alive and alert, let’s echo that in our own posture. Upright, energized but also with our spine relaxed and hands soft.

LANG LANG: Some teachers I study with in the past keep their students to themselves. They never let me play in front of other teachers. They always feel they know the most, that their approach is the right one. Gary is the complete opposite. He wants me to play for masters like Leon Fleischer and Claude Frank.

One Saturday afternoon, Gary and Naomi throw a party for me. Gary wants to introduce me to his friends, great conductors, musicians, and orchestra managers. “I want you to hear Lang Lang,” he tells them. “I want you to give him advice. I don’t want him to only hear from me. I want him to learn from a variety of great musicians.”

I’ve barely been in America for a few months. I sip raspberry juice, I avoid Gary’s vodka, and I play. The keys feel weightless under my fingers. The sound of the piano echoes across the apartment. Everyone watches, but it’s only Carnegie Hall that I feel staring back at me.

Gary’s perspective is that every great musician has certain specialties. Like how a restaurant has a signature dish. There is not only one way to Rome, there are a million ways to get to your final destination.

When I come to America I play mostly Western classical music. French music, I know well. German, Russian, that’s what I was taught growing up. But I don’t know Spanish music, so Gary shows me Granados, De Falla, and then Hungarian music, South American music. He even has me sit with a student of his who loves rock and roll, which he admits to not understanding at all. Even so, Gary insists that it’s important I expose myself to everything – that I take in as much as I can. He wants me to observe, listen and learn so that I can find my own way to think.

One Saturday, as I’m practicing, Gary hands me a book of Chinese music. “This is your history,” he tells me. “There are some interesting pieces that you may want to learn. Audiences in America will be interested in discovering Chinese music; it can be something completely fresh and different.”

Being in Gary’s orbit continues to unlock a connection to my own culture.

GUNATILLAKE: Sometimes it does take another to help us remember what matters to us. When Lang Lang talks here of better connecting to his culture, what comes to mind for you? Getting better at making a famous family dish? Reading that book you keep on putting off? Take a moment to reflect on what it is for you and make the intention to do what you need to to make it happen.

LANG LANG: In Philadelphia, at the Curtis Institute, I learn that as a pianist in America you have to be able to communicate your point of view musically, and you have to share your personality and ideas beyond music. My communication skills aren’t good enough yet.

In Asia, we’re not encouraged to express ourselves so personally. I am in the habit of keeping my feelings to myself. But Gary presses me to share what’s on my mind. It’s very hard for me to do so.

After six months Gary decides it’s time to change our strategy.

“Lang Lang,” he says, “You have to make real friends who are from America, who will become part of your day-to-day life. You can’t just be by yourself in a small circle of people with whom you never speak English. You need to get out of your little box.”

Gary tells me I need to get out and expand my circle, and then takes me to the same Chinese restaurant in Chinatown we have eaten at a dozen times!

With that, Naomi and him devise a plan. They introduce me to a former professor at the University of Pennsylvania who teaches Shakespeare, Rick Doran. We start to read aloud together – Hamlet, Romeo and Juliet, and numerous other plays.

We see Broadway shows. We go to the opera. I see my first American football and basketball game. A new world begins to open up for me. Back in Philadelphia, I eat my first cheesesteak. The lines are around the corner, the cooks keep yelling and everything smells like onions. I have to admit, it’s too heavy for me, and I can only finish half of the sandwich.

As we continue my education in the apartment, Gary shares stories from his adventures around the globe. These stories are my favorite. They open my eyes to a world outside of studying, practicing and playing the piano.

When Gary first visits China in the 1970s, bicycles are everywhere. So much that in the morning, before sunrise, it is the sound of bicycle bells ringing in the street that wakes him. It’s so different from the more modern China that I grow up in.

Gary shares stories of the sandstorms in the Gobi Desert along the Silk Road where the winds are so strong they turn cars into airplanes, lifting them right off the road. These stories are legends from China’s wild west, a China I had never seen.

It’s ironic that I have to travel all the way to New York to hear these stories. Being surrounded by Gary’s Chinese art and listening to his stories, I see the importance of not just learning more about western culture, but what it means to embrace my own Chinese heritage.

But I have come to discover that great music isn’t born in a vacuum. It can’t survive in empty space. Real innovation comes from accumulation – of knowledge, of art, of experience. It comes from understanding culture, people, history – and rejecting none of it. Especially your own history. All of these threads of knowledge come together to form a unique fabric, they shape and inform my approach to music in ways I couldn’t have ever anticipated.

Today people see me as an ambassador to the world for my culture. It wouldn’t have been so without Gary. And I think what makes him such a brilliant teacher is his conviction that the path ahead for me depends on my finding many teachers – to become an infinite student, infinitely learning.

I used to think that my life would find meaning when I answered the question: “How can I be the most successful pianist in the world?” Gary helps me ask a different question: “What does it mean to be a true musician?”

When I first came to New York, I believe that if I only worked hard enough, put in enough hours practicing, I would be the best. But it turns out that being a true musician is about more than hard work. It’s about more than what I put out, it’s about what I take in.

Exploring this question leads me to experiment with new foods, new art, new friendships, new music, and a new relationship with my culture – and, most importantly, with myself. Reframing the question leads me to accomplish things in my life, and in my craft, I not only never thought possible but never even imagined.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: There is a lot to take from Lang Lang’s story. But the theme I want to draw out in our meditation together is that of taking influence from wherever you can. Looking beyond our normal bubble, our normal behavior, and letting new input, new inspiration open us up to new possibilities. And we’ll start as with many meditations, with the breath. Inviting the body to be comfortable, soft. And taking some time to notice where you can sense the breath in the body. Entering, leaving. In, out. Inspiring, releasing. Directing your attention to rest with the breath a little while. Letting the mind collect here. Taking it easy.

When it comes to staying close to home, this is it. The breath is the most common object of meditation for good reason, but it is familiar. And as with Lang Lang’s path to becoming a true musician, it’s about what you take in. So let’s take some different things in. Let’s go beyond the breath.

First let’s go to the hands. Maybe the busiest part of our bodies. Drain as much of your awareness into your hands for a little while. Allowing them to soften. Notice any energy here. Any pulsing. Any vibration. Watch the dance of sensation that is here in the hands, however they are. Even if they’re not doing much at all. Taking in the hands.

The second place we’ll go to on our tour is to the heart. Another area that works so hard. Blood and emotion. Letting the mind be quiet, move your attention to the center of the chest, in and around the heart. If it feels ok and is safe, you can close your eyes if you like. Such an important part of us. So much to be felt. Often ignored as an area for our attention. So resting here. Taking in the sensations. Taking it all in. Touch, feelings, reaction. Taking in the heart area. Taking in the heart, the heart area.

Okay, in a nod to Lang Lang’s day job, let’s now open our mind to take in sound. Not listening to anything in particular, not even my voice. Rest with the overall soundscape that is here to be known. Open to near sounds and far. Open to unexpected notes. Letting the mind, the awareness be open and receptive and allowing sound to come to you, no need to go out and grab it, no need to do anything. Taking in whatever arises in the soundscape, whatever music. Taking it in.

We’ve gone beyond the breath, and looked to new parts of experience for input and insight: the hands, the heart, to sound. For this last leg, let’s go further still and turn the mind to mystery, to the place where music is before it’s written or played, to the place that is neither here nor there. If those words resonate at all, go with that resonance. And if they feel confusing, go with that.

Every time you listen to an episode of Meditative Story, you do what Lang Lang was invited to do by his teacher. You take on something outside of yourself, a story, literally alien. And in the doing you open yourself up to new directions, new perspectives.

Take care and be well. And thank you for inviting us into your life.