To be seen on my own terms

Lex Gillette is a 5-time medalist at the Paralympic Games, and a world record holder in the long jump, but he’s more than that too. As he learns to navigate the world after losing his sight, he’s worried about being left out and overlooked — or, just as bad, being seen only in terms of his disability and his athletic gifts. Lex shares the story of how he began to forge his identity on his own terms, creating a spotlight that he steps into with his entire being.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

To be seen on my own terms

LEX GILLETTE: There’s a runway — 114 feet. I hear a verbal cue from my guide. I know the number of steps I take before leaping from the takeoff board. I leap fearlessly as far as I can into the sand pit. The pit doesn’t care where I’m from. It doesn’t care what color I am, or my beliefs or my disability. It just wants me to fly.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: When Lex Gillette loses his sight at eight years old, his world grows smaller. It’s harder to play with his friends. He is afraid of being overlooked or being seen primarily for his disability. This changes when he becomes a five-time Paralympic medalist for the long jump and a world record holder, but still there remains an essential part of him that wants to emerge. In today’s Meditative Story, Lex shares how he learns to forge his identity on his own terms, to share his other gifts with the world.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind, open. Meeting the world.

GILLETTE: My mom and I walk down Wake Forest Road in Raleigh, North Carolina. We pass all the landmarks my six-year-old brain can already name from memory. The McDonald’s, where I get my Happy Meals. The Kmart, where Mom buys things for the house. The car dealership. I recognize their logos immediately. They’re full of the primary colors I love.

We cross over a bridge, and I finally see our destination: Biscuitville.

As soon as Mom and I walk in, the smell knocks me in the nose. Sausage biscuits, french toast sticks, and bacon. We get in line, and I look through the glass at the sweet old women who work the counter. Their hair swept back by hairnets. I watch them make biscuits from scratch behind the glass.

I cherish the images from my neighborhood even more when I start to lose my own sight. Mom is visually impaired, and now I have retinas that are gradually detaching.

Turning eight, I begin my year of hospital visits. I have over 10 operations. Listening to my doctors, I have a glimmer of hope. They keep saying, “We’re going to fix this.” But the last operation isn’t successful. We’re at a point of no return. I feel defeated.

Each morning I wake up, my world gradually grows dimmer. It’s disappointing. Frightening. My friends now play Super Nintendo without me. Socially, I feel my world shrinking. It fills me with new insecurities. I worry that because of my blindness I will be overlooked by my friends, unseen by my community and by the rest of the world. I’m still surrounded by the objects from my old life. My video game console. The electric keyboard I got for Christmas. I sit in our living room and run my hands over the keys. The sound of the notes ascending feels comforting. I picture the exact day I got it.

I see the snow blanketing the cars outside my window Christmas morning. In our living room, the tree that my mom and I decorate together has candy canes hanging from the branches. And then, my keyboard, unwrapped and set under the tree, like Santa sat down for a jam session in the middle of delivering it. I tap the keys with my right index finger, playing Happy Birthday. I sing along.

One evening, a member of our congregation visits. She says, “Stevie Wonder plays the piano. Ray Charles plays the piano. Oh yeah Lex, you could play the piano too.” I hear the same thing on repeat from friends and neighbors. I can’t see, but I don’t need them to plan my future for me. Playing music would mean I’m out there in front of people — talent shows, church service, exposed. I’m afraid of being overlooked, but I don’t want to bring attention to myself.

So once I lose my sight, instead of practicing music, I do what no one expects me to do. I run.

I run around our neighborhood, taking the turns I know are there. I jump off the concrete ledges. Sometimes, I fall and scrape my knees. But still I go as fast as I can, trying to escape gravity. Trying to escape what other people think is possible for me.

GUNATILLAKE: Can you feel the freedom, the speed, the exhilaration that Lex is expressing here? Well worth the odd graze or two. When did you last move with this fearlessness? If you can’t remember, how about you make the intention to do so? I am.

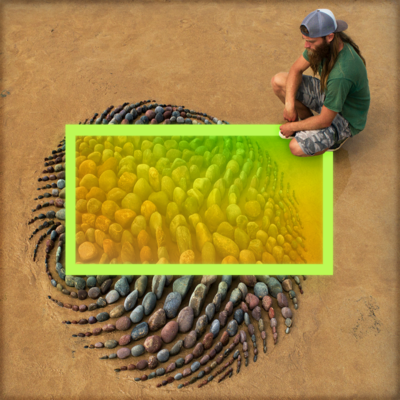

GILLETTE: In high school, I love track and field. I travel from North Carolina all the way to Michigan for a sports camp for kids with visual impairments. Coach Whitmer convinces me to try the long jump. I’m not sure at first. I’m totally blind and propelling myself through the air. I’m front. I’m center. I’m visible. There’s a runway — 114 feet. I hear a verbal cue from my guide. I know the number of steps I take before leaping from the takeoff board. I leap fearlessly as far as I can into the sand pit. The pit doesn’t care where I’m from. It doesn’t care what color I am, or my beliefs, or my disability. It just wants me to fly.

My giant leaps through the air define the next years of my life. I do it for the rest of high school, then college. The track becomes a place of comfort for me. I drop into this zone where I know what I’m here to do, and how to do it. I’m not fulfilling other people’s expectations. I’m learning to create my own.

During my first year in college, I’m sitting with my girlfriend at her place. I feel the warmth of the Raleigh summer. Her hands are on my hands, which are on the piano keys. She tells me, “This is where your thumb goes. This is where your middle finger goes. Now when you transition to this chord, your pinky goes here.” Her hands show me the way.

My girlfriend can play the heck out of this piano. When I hear her play, I get jealous. I tell myself, “Oh, man, I need to find my way back to music.” Years ago, I cut myself off from it, not wanting to be judged. But when we play together, I’m not thinking about what people think. I want to access the joy of music the way my girlfriend does.

So she takes me to the local music store, and we settle on a Casio 61-key keyboard.

When I start, there’s a gap between where I am and where I want to be. It was true when I learned the long jump, and it’s true again now. I keep leaning into this flicker of passion.

A few months later, I stroll through a mall in Greenville. It’s full of people. The line I stand in is long. All around me is the chatter of contestants, nervous and excited. I can smell the Cinnabons and pizza wafting from the food court.

I’m in this line because a local radio station is hosting a singing contest. They’re looking for the best singer in the region. One of my friends says: “Lex, you gotta put your name in the hat and try out.” I’m not where I want to be with my piano playing, but I know I can sing.

Waiting here in line reminds me of waiting for a track event. Except that when I’m warming up as an athlete, I know what to expect. But here in line to audition as a singer, there’s only one way to put it. I’m scared.

When it’s finally my turn, there’s no going back. I‘ve got 90 seconds to sing. No instruments. Just my voice. Rather than shrink from my disability, I’m choosing a Stevie Wonder song. Microphone in my hand, I start the first notes of “Ribbon in the Sky.”

As my voice fills the space, I feel naked, like you can see everything about me, inside and out. I’m torn between not wanting to be this vulnerable and exposed, and wanting, fully, to be seen.

I take my first few strides and try to find my arena of comfort. I create a spotlight for myself and step into it with my whole being. It feels like this is my own thing, on my own terms. What society thinks I should or should not do, what I can and cannot do as a person with a disability fades into the background.

The feedback from the crowd makes its way back to my ears. I hear the cheers. The hollering. They’re with me.

I don’t always trust applause. People might be encouraging me like I’m a 2, 3, 4, year old child. They might think, “I don’t want to break his spirit.” But not today. This connection feels real.

I kill it. It feels amazing. Like there’s no resistance, no gravity.

Years later, I climb the stairs of the two-level residence building that’s part of the Olympic Training Center Complex in Chula Vista, California. Once I get to the top of the stairs on the second floor, I walk to our front door in four long strides.

Room 324 is where the magic happens.

Right now, it smells of stinky shoes from training and leftover carne asada fries from Lolita’s. I pivot left and sit down in front of my keyboards.

I like to play before and after training. Music and sports let me fly in different ways. Where once I wanted to hide from people who might be looking at me or judging me, now I see how music helps me communicate who I am and how I feel in new ways. As a blind person, I still struggle with the constant reminders of feeling isolated, of feeling overlooked.

My entire social circle are my teammates, some of whom I share this suite with. One evening they’re going to a club downtown. Everyone’s getting ready. I can smell their cologne. I hear closet doors slamming, and different shoes being put on the ground. Questions fly from one room to the other. “Should I wear the Chelsea boots or the Jordans?” “The blue or the black?” Sometimes someone says, “Oh, what’s going on, Lex? How you doin, bro?” But no one asks me to join them.

I get it. No one wants to babysit the blind guy. But I bookmark this moment and countless others like it. My challenge is to come up with other ways to be seen, to connect with people. Sitting here I tell myself, “You need to stick with singing and songwriting, because this is going to be your way to communicate with the rest of the world.”

GUNATILLAKE: We see you Lex. But what would it be like if we were right now to really see ourselves and how we are trying to communicate our unique ideas with the world. Let’s try that now. Letting go of any judgment that arises with that.

GILLETTE: Wesley’s Williams is my guide runner. He stays in room 323 next door. His job on the field is to be as loud as possible. He’s the one who paints a mental image for me so I know where I am at all times. Off the field, it’s often his voice I hear in our living room, making jokes and laughing. Whatever changes around us, Wesley is a constant and becomes my closest friend.

We’ve been working together for almost five years. And right now, we’re staring down the barrel of the 2012 Paralympic Games in London.

One day Wesley tells me his mom has never seen us compete in person.

This stops me in my tracks. I know the pride my own mother feels at our competitions. I say, “Man, there has to be a way to get her to London.” We put our thinking caps on. How are we going to raise the money to fly her there?

Now, I’ve written songs before, nothing public, just little things I play for my roommates. But now, I want to write a song we can sell for the cause. Something that captures the incredible moment of standing on the podium in front of thousands and thousands of people.

Sitting at my two keyboards, I feel myself drop into the zone. I know what I’m here to do, and how to do it.

I start with the chords — G minor, A, B flat… I work until they form a rhythm and order. I know it’s good when the sound starts to feel like a massage on my eardrums.

I write about standing on that huge stage, when they call my name, and the five seconds you have to take in that this is happening. Feeling the weight of the medal around my chest. The people in the stands, at home, watching and cheering. There’s no pity in these cheers, just excitement and joy.

“Emotions running high. Every single stride. But this is why I fight.”

I head into my bedroom to lay down the vocals. Better acoustics require being in a tight space. So I lift up the front two feet of my bed up on cinder blocks, then crawl into the space beneath. I tie the microphone to the bottom of the bed frame, and sing in this little cave. No echoes. The sound is warm and good. I feel unstoppable.

This song connects me deeper to Wesley and us both to his mom. And through the lyrics, I feel myself connecting to the rest of the world. The vulnerability I once felt playing music has radically evolved. It’s less about me and more about us.

As the U.S. Paralympic team approaches the entrance, we’re laughing and having a good time. But once we walk into the big tunnel leading to the field, we know the drill and quiet down. We’re on the cusp of one of the largest spectacles on the planet: the London Paralympic Games.

The ground is carpeted beneath our feet, and it starts to incline as we reach the mouth of the stadium. Then — BOOM — I feel the space open up. Electricity hums in the air. I feel the warmth of the lights, and the cheers of 85,000 people. It’s so loud I can’t even hear Wesley beside me.

But then, as we march around the stadium, something unexpected happens. I hear Wesley shout. Somehow in this huge, sold-out crowd, Wesley sees his mom.

After our events, I meet her inside the Athlete’s Village. She wraps her arms around me. She’s proud of her son, and I’m proud too. We sold our song to thousands of people. My song helped create this moment.

When I compete, it’s about more than just, “I can run fast and jump far.” That’s only half the story. The other half is how I got there, defying the gravity of people’s expectations. We can all use our best gifts to find ways to be seen and to be heard. When I run and jump, I’m speaking to the world with my body, telling them that I refuse to be held down.

Now, singing allows me to create my own spotlight, one that I step into fully, with my whole being. I don’t have to forge an identity through the way the world sees me.

I’m not Stevie Wonder. I’m not Ray Charles. I’m unapologetically me, Lex Gillette.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Lex.

Lex’s story is so rich and powerful. I’m basing our meditation today around some of the moments I found most profound.

“When I compete, it’s about more than just, I can run fast and jump far. That’s only half the story. The other half is how I got there, defying the gravity of people’s expectations.”

There is often that hidden half, isn’t there? The parts of our lives that people don’t always see but without which our more public lives, even our celebrated moments, just wouldn’t exist. It’s the decent night’s sleep that gives us brightness in the mid-morning Zoom call. It’s the mindfulness or yoga practice that supports the calm and the kindness that others see in us, enabling the moments that others see and celebrate. The other half.

The other half. Half and half. The in-breath, and the out-breath. The in-breath, with all its glamour of bringing oxygen into the blood and the body. Inspiration. But it needs the out-breath, the more worker-like job of scuttling out the unwanted. Let’s enjoy these two halves. The in-breath and the out-breath. Giving them each equal attention, but gentle — shoulders, face relaxed.

Celebrating the out-breath. Celebrating the in-breath. Letting the simplicity of just paying attention to them be our gratitude, our thanks. The in-breath, and the out-breath. Half and half. One, but not one.

“The pit doesn’t care where I’m from. It doesn’t care what color I am, or my beliefs or my disability. It just wants me to fly.”

For Lex, the pit at the end of his runway is all accepting, it allows him to be however he is, without judgment.

Our awareness can be like this. Whatever arises in our experience, in mind or in body, it is contained. It is known.

So now that our two friends, the halves of the breath have helped up settle, let the mind, the awareness be big. Like a big sky. Or an infinite sandpit. Whatever arises, whatever lands, is known and held. The distracting thought, a delightful feeling, a memory, an itch, a mood, it’s okay. You’re all welcome. All received.

Inviting our mind, our awareness to be that sky, be that pit. Not interested in the stories of what arises, not interested in the labels. We don’t care about that for now. Awareness, senses, mind: open — just knowing in the bare experience.

Open. Accepting. No need for judgment or commentary. The naked experience is enough.

“We can draw the lines of our own spotlight. When I run and jump, I’m speaking to the world with my body, telling them that I refuse to be held down.”

Following Lex’s invitation, let’s drop our awareness back into the body.

The whole body, known, in whatever posture it is right now.

The whole body breathing in. The whole body breathing out. The whole body, known.

What message is your body saying? Is there a message to you? Is there just a tone, a vibe?

If there is, then acknowledge it.

Maybe the body is saying “I’m stable.” Maybe it’s saying “I am open. I am with you.”

Let’s listen. And letting go of any self-criticism or body judgment for now. Let’s just listen.

What is our body speaking? What is it speaking to the world? Let it speak.

Thank you Lex again, so much. And thank you.

We’d love to hear your reflections from this episodes. You can find us on all our social media platforms: @meditativestory. Or you can email us at [email protected].