My monkey teacher

Psychology professor Dr. Laurie Santos is the host of The Happiness Lab podcast – and of Yale’s most popular course ever. (More than 3 million people have taken her “Science of Wellbeing” course online.) In this story, journey with Laurie to an island in Puerto Rico where she is one of only a few humans among thousands of monkeys. The company of non-humans, it turns out, can help us better understand ourselves.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

My monkey teacher

LAURIE SANTOS: The moment our plane touches down in San Juan, I join the other passengers in the ritual of cheering and applauding. Everyone is always happy to land in Puerto Rico.

I’m happy to be here too. My first semester of graduate school has been intensely lonely. I chose to stay at the same school where I went to college, but all my friends have moved away. So I’ve packed paper, envelopes, and stamps with me on this trip so I can stay in touch with friends who are now scattered all over the country. It’s 1998. There’s no wifi, or emails, or text messages.

Normally I come to Monkey Island on Thanksgiving. But this year, I’ve got a lot of dissertation research to do. Which means, I’m here over the winter holidays too.

For long parts of the day, I’m literally the only human being on a huge island with 1,000 monkeys. This kind of solitude is of a different nature entirely than anything I’ve experienced in my life. The presence of all these other beings makes me feel alone but also connected all at once.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Laurie Santos is a professor of psychology at Yale University and host of The Happiness Lab podcast. Her “Science of Wellbeing” course became the most popular in Yale’s history. More than 3 million people have taken the online version.

In today’s Meditative Story, Laurie journeys to a remote island where she spends time as one of only a few humans amongst thousands of monkeys. Let her story transport you into this world where being in the company of non-humans helps us better understand ourselves. Laurie asked me to clarify that some of the scientific practices described in her story are no longer allowed on Monkey Island, as research and safety practices have become more well-considered in the intervening decades.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

SANTOS: It’s my freshman year of college. On a whim, I decide to take a human evolutionary biology class. Early during the semester, the professor shows slides of his field site. It’s this beautiful tropical island… like literally your dream island in the middle of the ocean – you know, the first thing that comes to mind, palm trees in the middle of turquoise sea. The next slide is a bunch of adorable monkeys running around a beach and throughout the forest. And then the professor says, “We need research assistants during Thanksgiving break.” I’m like, “This sounds amazing. Sign me up right now!”

Cut to several months later, it’s 6:45, and I’m sitting on a small dock with a half-dozen other students and my professor. We’re waiting for the boat that will take us to Monkey Island. It’s hot as blazes. The sun has just risen, and the ocean is shimmering. When the boatmen show up, we clamber into his little dinghy-sized speedboat.

A nervous, and kind of excited energy circulates between all of us, and not just because of the animals. We don’t really know each other that well, and we’ll be living in very close quarters for the next week. Will the other students like me? Will I be able to take the heat? I already really miss the air conditioning.

We pull up to the dock on the island, and there are mangroves on all sides, their roots reaching like fingers into the water and up on shore. We grab our packs and walk down a little tunnel of mangroves. It smells like salty air mixed with some sort of sour organic matter, which I later realize is monkey poop.

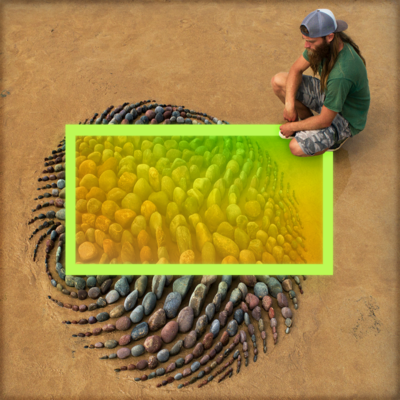

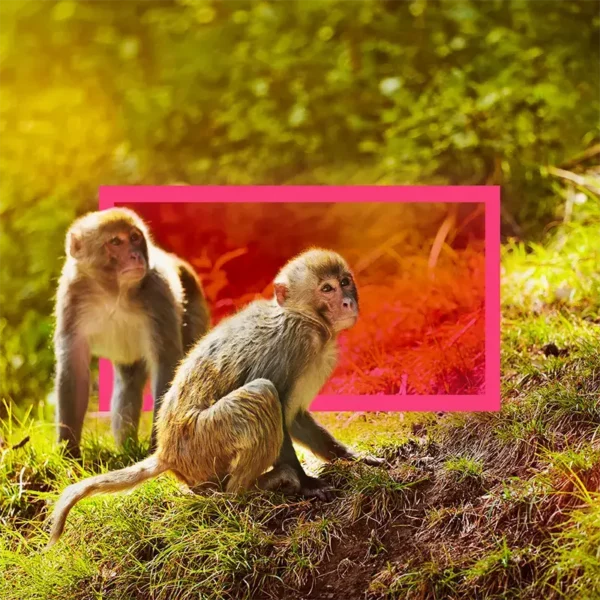

As I’m walking I notice some movement and look up, and there he is my first monkey. I gasp. There, right there, is a rhesus monkey in a tree! He’s the color of wheat, with a wrinkly wide-eyed face, like a surprised grandpa. The genetic similarity we’ve known to have with rhesus monkeys suddenly and vividly just comes to life for me. I snap a picture with my little point-and-shoot camera. I step closer and snap another. Then another. The students who’ve been there before just kind of walk right by.

As I walk through the rest of the mangrove tunnel, I see it: a large green shed with the words Caribbean Primate Research Center on the front. As I get closer, the trees thin, and I realize I’m looking out at a big, flat open clearing. And that’s when I notice them: hundreds of rhesus monkeys, sitting in large clusters on this gently sloping hillside. There are mothers holding babies, young males scampering around the edges, lots of others just sitting upright with their chests out. They are all the size of large house cats.

The monkeys start making little noises, a vocalization like “Hrn, hrn,” all at once. A big chorus of “hrn.” They’re all chattering and cooing with increasing volume. What is going on?

Then I see a truck drive to a fenced-in feeding area and dump what must be hundreds of pounds of monkey chow: they’re little nuggets the size of big Tootsie Rolls.

The monkeys absolutely lose their mind. Many run towards the feeding area, dozens at a time, pushing, and tackling, and shrieking, and shouting, hitting, and trampling all over each other. Others hang back, looking a little stressed. I know enough to know there’s some deep social dynamics at play here – but so far, I can’t really make any sense of it.

We spend the week helping my professor with his experiments, observing the monkeys, and writing lots of notes.

I watch them nuzzling their mates or their mothers when they want to be groomed, looking dejected if they’re turned away, and satisfied when the grooming begins. Sometimes they want to hang out with each other, and sometimes they want to be alone and just climb a tree.

I watch two female rhesus monkeys fawning over a third female’s new baby, grooming it all together.

I watch two adolescent male monkeys tussling in an attempt to show off and try to move up in the world.

They’re so obviously different from humans, but I’m struck by how similar a lot of their wants and needs are.

They seem to have the same basic goals that we do in life: family, status, food, relationships. They want to belong and be liked and be comfortable. But they navigate these problems without language or technology. All they have is this straightforward, even sometimes comical, behavior. They’re not waiting for an invitation to a gender reveal party. They just pick up a new baby’s tail and look for themselves.

The monkeys also make me realize that it’s sometimes me who is a little monkey-ish? I mean, I get hungry. I love my family. I want cute boys to like me. I want to be recognized for doing well academically.

As I board the flight back to Boston from Puerto Rico at the end of the week, I think: Well, that was cool. I’m pretty lucky that I got to do that probably will be the only time. I mean, I’m not an outdoorsy person, and so I’m definitely not going to miss the dirt or the heat. So I got on that flight quite sure that I was never going back.

Eleven months later, when my professor asks who wants to go back on the annual Thanksgiving trip to Monkey Island, my hand shoots straight up.

In the intervening months, I’ve been working in this lab, and I’ve grown more and more fascinated with these monkeys, and with the human mind. The central question we’re asking is, I suppose, kind of an ironic one. We’re studying these monkeys, not to know about monkeys. We want to know what it means to be human.

As we take the early morning boat to Monkey Island, I’m one of the few students who has been there before, who knows what to expect. It’s me who can show people around this time.

We’re interested in what makes humans unique, and so we’re studying the kinds of things that we think make our species special – things like counting. We run an experiment using a very simple magic trick. A partner and I walk around with a foam board box. We find a monkey who is sitting all alone. I take an eggplant from my backpack and put it inside the box, I then cover up the box, and place a second eggplant inside. When I open the box, how many eggplants are inside? Are there two eggplants there? Or only one?

When one eggplant plus one eggplant equals two eggplants, the monkeys will watch for a second or so, but quickly get bored. But when one eggplant plus one eggplant equals only one eggplant, when I’ve taken one away surreptitiously, the monkeys look for a really long time… significantly longer than before. They seem to be surprised. Which tells us that monkeys can count! And it’s these small breakthroughs that keep me coming back to Monkey Island, year after year after year.

GUNATILLAKE: We can count too. One on the inbreath. Two on the outbreath. However your breath is. One. Two. One. Two.

SANTOS: By the time I make it to graduate school, I know the drill. The moment our plane touches down in San Juan, I join the other passengers in the ritual of cheering and applauding. Everyone is always happy to land in Puerto Rico.

I’m happy to be here too. My first semester of graduate school has been intensely lonely. I chose to stay at the same school where I went to college, but all my friends have now moved away. I’ve packed paper, envelopes and stamps with me on this trip so that I can stay in touch with friends who are now scattered all over the country. It’s 1998. There’s no wifi, or emails, or text messages.

Normally I come to Monkey Island on Thanksgiving. But this year, I’ve got a lot of dissertation research to do. Which means, I’m here over the winter holidays too. Or, at least that’s what I thought, because in Puerto Rico they keep vacationing for two weeks after Christmas.

For long parts of the day, I’m literally the only human being on a huge island with 1,000 monkeys. It feels really different not having the other researchers around. Humans groom each other with banter and gossip, and these days, I’m really missing it. This kind of solitude is of a different nature entirely than anything I’ve experienced in my life. The presence of all these other beings makes me feel alone but also connected all at once.

My graduate work is about how monkeys think about food, and how they learn that new food is safe. But my pilot studies aren’t working. I make fake food out of playdoh and pretend to eat it, but the monkeys aren’t really fooled, and I’m not getting any great data. I’m frustrated, I’m hot, and I’m alone. I’m wondering, will my thesis even work out? I feel my chest tighten up.

I’m hungry, and I just want to go somewhere pretty with my sandwich.

These days we usually eat lunch inside a cage, because it’s more protected there. But back in 1998, you could eat wherever you wanted, and I decided to eat on the beach. Monkey Island is actually two mini islands, connected by a little isthmus. It’s one of the few sandy spots on the island. Sometimes, it’s a high-traffic area, with monkeys crossing from one side to the other. But I knew at lunch time the spot would be deserted because it’s hot, and there’s no shade.

I walk out into the middle of the Isthmus just so I can make sure that there are no monkeys there trying to roll up and steal my food. I sit down and pull out a little brown paper wrapper holding my ham and cheese sandwich that I bought earlier that morning at the panaderia. It’s pressed like a Cubano, and the cheese is still warm and melty. It’s my favorite sandwich ever, and particularly delicious today.

As I chew my first bite, I see a monkey walk out onto the isthmus. He’s about 30 feet away or so. And it’s not just any monkey, but one that I know really well. We call him Chester. He’s distinctive because he has a crooked head. It happened when he fell out of a tree back when he was little. He’s a pretty low-ranking monkey, still a teenager, skinnier than most of the other ones.

Higher-ranking monkeys tend to claim all the shady spots, which means that monkeys like Chester get chased out here and have to eat on the outskirts. That’s why he’s here with me.

Chester is an outcast, a young loner monkey. The other guys probably think of him as a loser. I look at him chewing his monkey chow, and I think: wow, he’s just like me.

Chester with his crooked head, me in my ratty t-shirt, and beat-up jean shorts, my hiking boots covered in monkey poop. Neither of us know how we’re gonna make our way in this big rough world. But, we’re here together because we both wanted a peaceful spot to eat – and honestly, neither of us wants to be alone.

We make eye contact for a brief moment and then keep munching our lunches.

I’m stressed about where my research is going or not going, and what I’m going to go home to. But Chester, he’s not doing any of that. He’s just eating his monkey chow and looking at the waves. He’s fully present. Or at least he seems to be. Maybe he sees me eating and thinks I’m fully present. It’s all odd. But at the same time, it’s so human this experience between us.

It will be years before I learn much about meditation, but already I sense that there’s something reassuring about Chester’s take on the world.

People who practice or teach meditation often talk about the monkey mind – that so-called frantic state in need of taming. But Chester’s monkey mind is clearly more peaceful than mine. He’s not angsting about the future. He’s not re-playing all his mistakes. Monkeys get a bad rap, I think, finishing my sandwich. The monkey mind should actually be what we’re all trying to achieve.

GUNATILLAKE: Picture quietly observing Chester, as if you’re Laurie at this moment. Watch him look out over the waves, quietly eating… just being in nature alongside you. He’s a quiet companion. Notice the simplicity. Notice the carefree nature of his movements. And if this instruction makes sense to you, invite your monkey mind to settle down.

SANTOS: I’ve now gone back to Monkey Island every single year for 27 years. Some people have a getaway place on Cape Cod, mine is an island full of rhesus monkeys. Whenever I go to Monkey Island I can feel the passage of time, I’m watching all the changes. Coming back to the monkeys feels like a soap opera where I’ve missed a few episodes and have to catch up. I learn how so-and-so monkey is doing, who’s moving up or down in the hierarchy, and who’s had babies. Same goes for the people who work there. One of the men who runs the boats and feeds the monkeys has retired, and his son is working there now.

And then there’s Chester. Amazingly, my crooked-headed lunch date becomes one of the highest-ranking monkeys on the entire island. Female monkeys are born into their rank, so they know from birth what their position is. Males like Chester normally have to fight it out, but he’s used another strategy: He’s hung out in his group so long that eventually he just made friends with everyone. He’s risen in stature basically through attrition.

Accordingly, his behavior shifts: He doesn’t have to hide away from the group; he gets to eat first, and so he puts on some weight. He eats in all the shady spots, surrounded by the attentive females.

I’m rising up the ranks too. I go from a college student, to a graduate student, to a professor, to a tenured professor. I meet a boy I really like, bring him to Monkey Island for one of our first trips, and eventually marry him. I’m finally able to stay in the nicest accommodations in our little Puerto Rican town while we’re doing research, the ones with kitchen appliances and real air conditioning.

I don’t have pets or my own biological kids, but I have lots of academic children. As with the monkeys, there are generational shifts. One of my graduate students becomes the director of primate research on Monkey Island, and I swell with pride. I become the head of a residential college where I’m like a mom to 400 students. I experience all their excitement over their acapella performances, and sports wins, and I soothe them when their parents divorce or when they don’t get their internship.

Watching the students brings me back to my picnic on the isthmus. These days they can’t eat over there, but I watch the same distress that they have with their spinning minds. And that’s why I created my Happiness course. Other animals certainly experience anxiety of various sorts, but our particular kind of worrying mind? It’s singularly human. We can’t shut it off, and that’s what leads us astray. Our minds aren’t necessarily built to help us to become happy, and so we need to understand the right strategies like meditation, the arts and tricks of becoming more sensory, more present.

I’m in New Haven in my office when I get the news. Chester has passed away. Monkeys only live into their 20s or 30s, it’s a sped-up version of our own lifecycle. Over those years our world has only gotten trickier for finding community and reflection and happiness. If I’d sat down on the isthmus today to eat my sandwich, I might have been busy checking my Instagram. I’d probably never notice Chester sitting only a few feet away. Honestly, I feel lucky. My student’s voice is pretty mournful as she shares the news with me. It’s as though she senses the truth – that losing Chester is like losing an old friend.

He’s one of the most unlikely teachers I’ve ever had.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Laurie’s right. The idea of the monkey-mind is an old and well-established one in the meditation world. And what it originally refers to is how the mind jumps from place to place, from thought to thought, branch to branch. The idea of the mind uncontrolled and in response, the meditation world creates an arsenal of techniques to bring it into line. To make the mind do what we want it to.

Hmm. That is one way of training the mind for sure. Giving it a task to do and bringing it into line when it strays away.

But what if our mind is more like Chester? And we trusted it.

Trusted that if we just sat and ate our sandwich, it’ll actually be quite chill and hang out with us. No big deal. Bring no drama to the party. If anything, it’s more chill than you already.

Minds get a bad rap. What if it was already how we wanted it to be?

Let’s practice that.

Sitting like Laurie, or however your posture is. And just letting your mind come to you. Not asking anything of it. No bargaining. No judgment.

This high ranking mind, that has learnt so much, has been so patient, has served its time. Now here.

Letting your mind be how it is. And being here for it.

If you’re really still, you can move even closer to your mind without startling it away. And watch it. It’s a teacher. So what lesson is here, being taught?

Trust your mind. And trust yourself in your ability to be with it.

We are different to other animals though, even those closest to our DNA profile. So to close the meditation, bring to mind your favorite quality or activity that only we as humans can do. And appreciate how we are the furthest along the evolutionary story, for now at least, for all the challenges that brings.

Rhesus monkeys share about 97.5% of our own human genome. Let’s own the similarities, our animal nature. But also celebrate our difference. That we can angst about the future. And that that’s OK. Holding all that at the same time.

Thank you Laurie, thank you Chester.

And thank you. Go well.