Navigating life in my own skin

Sitting in the back seat of the family Buick on a road trip, a 5-year-old Zenju Earthlyn Manuel (now a writer, artist and Zen priest) keeps an eye out for cowboys and dreams of the Wild West. In the front seat, her parents sit, tensely navigating an altogether different landcase. It’s 1957 and they’re winding their way from LA to Louisiana, and a wrong turn, an absent-minded stop to stretch their legs could mean so much more than just getting lost. In navigating this trip, Zenju learns more than just how to get from place to place: she learns how to find her way in the world, in her skin.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Navigating life in my own skin

ZENJU EARTHLYN MANUEL: Our morning is filled with more landmarks to reach Opelousas, Louisiana: Go past the house without the roof, turn left at the post office and go past the meadow with the cows. When you see the fork in the road go straight or else you’ll end up on the wrong side of the train tracks.

When we arrive within a day, I look up into the dark wide face of Auntie Ola, the place marker that said we were from Louisiana even though we were born in California. She’s the marker that confirms the shaping of our image into the land on which my father and mother were born. She’s the one who holds the same memories as Daddy. I can’t take my eyes off this coal black woman with soft black hair, who is Louisiana herself – and I belong to her.

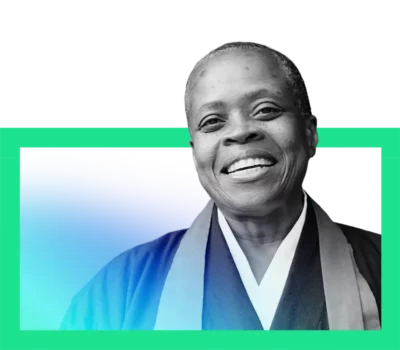

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Zenju Earthlyn Manuel is an author, poet, ordained Zen Buddhist priest, teacher, and artist. And the Zen tradition she’s in the lineage of is one I hold very dear. One which emphasizes simplicity, clarity, wisdom and beginner’s mind – the mind of many possibilities not yet constricted by certainty. She gives us a beautiful poetic read of a story she wrote that transports us way back to her childhood. It is full of light, light which points us back to ourselves.

In this series we blend immersive, first-person stories with mindfulness prompts to help you restore yourself at any time of the day. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide on this episode of Meditative Story. From time to time, I’ll come in ever so briefly with guidance as you listen to the story. Some prompts may help. Others may not. That’s okay.

And now onto the story. The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

EARTHLYN MANUEL: We take only one family trip to the strange lands of Louisiana and Texas. I’m five years old. It’s 1957. The palm trees of Los Angeles are left behind. I had been living in my swing to avoid getting in trouble. Pushing in and out until what hurt began to die.

In this period, metal wings of police helicopters don’t drown out the flutter of hummingbirds. There’s no disrupting those rare moments where we can breathe and meditate like monks and nuns, right where we stand. I jump into the backseat of our black fat Buick, along with my sisters, ages 8 and 3. Mom fusses about making sure the luggage is secure in the trunk, not that they’re overloaded. She worries because if we lose the few shoes and clothes we own, it means we lose everything.

The plan is to travel to Louisiana by landmarks because having been born in 1898 Daddy can’t read, and Mom doesn’t drive or understand the direction of the highways. To her, going one way or the other looks the same. I settle back in my seat despite our situation. We’re going back home.

The place that shaped my parents. My sisters and I aren’t from this place. But perhaps “we” are going back home too? Because we’re a work-in-progress being shaped like them, eating Gumbo only in the winter when the crabs surface, and being fiercely superstitious in an effort to ensure that we don’t cause our own unfortunate illness or death.

Since we’re all shaped alike, we’re all going back home, back from having gone forward away from being so country in our ways. Back to Louisiana. Back home was where Daddy, the last sibling of 20 children, would visit with his youngest sister Ola. To return to Auntie Ola is to go back to a marker in my father’s book of life. It’s a place in his story he has remembered for fifty plus years.

To release the red soda water my sisters and I had consumed, my father pulls off the road for us to squat and pee. The air glides its hand along our naked behinds. No shame, just a lesson in necessity. Like it’s a necessity to heed the signs on the road that aren’t there: Bring Your Own Fried Chicken. Don’t Stop Along the Way from California to Texas or You Might Be Killed by the KKK. Keep Going Straight Ahead. Pee Over There. Stretch Your Legs Down The Way. These are the invisible signs behind the real signs that my father can’t read.

“Are we there yet?” Mom laughs in the way that makes me feel like I’ve asked something foolish. She does that often. I don’t understand the reason why what I said is particularly funny. I’m embarrassed. What I mean is: When are we going to stop and see those cowboys like on the Saturday afternoon movies I watch with my father, after he cooks the rice and sautées the canned salmon with onions. What I mean is that the mountains are so big they seem like they might crumble from their height and crush us. What I mean is I have a headache. What I mean is I don’t trust that they know the directions.

The road seems to be going nowhere. A black child without a destination is a child with no future. I need a future that will show that the pain of being black will disappear someday, and this trip is proving painful. So the future should be close enough to see, smell, and feel no pain.

I had told my entire class at school that I was going on a vacation. I had never been able to say such a thing. I wasn’t going to where they were going that summer: Paris, Hawaii, or Yosemite – which I thought for a long time was in another country. We aren’t flying, taking a bus or a train that can take us exactly to where we need to go. No, we‘re going to Louisiana by way of landmarks through Texas, in a fat black Buick that smells of gasoline once it’s filled to the brim.

At the border between California and Nevada the guard begins to ask my father questions that I’m afraid he can’t answer. Lawrence Manuel, Jr. is silent, a silence of courtesy, of an imposed respect as a black man, or a protection from being found driving while illiterate, protection from being maimed or killed.

I want to say to the man in the uniform with a pistol at his side, “My Daddy’s a quiet man.” And because Daddy and Mom are shaped by silence, we are shaped by it. We’re a quiet family traveling without listening to the radio or talking hardly at all to each other. It’s an entirely silent trip, moving about from one state to another, looking for invisible cattle gates that are meant to keep us from crossing borders of any kind. We dare to take a vacation without knowing where we’re going. Home is that way? Or is it this way?

GUNATILLAKE: Have you ever gone on a trip without knowing the way? Does the idea of getting lost make you excited or afraid?

EARTHLYN MANUEL: Route 66 leads into the desert where there’s nothing but hot. With no buildings for Daddy to follow like he does in the city, no street lights lighting up those landmarks. We go as we’re told, like the old folks had told him to come across the river and then come around the mountains. Follow the bend to the left then come up over the hill, and stop at the hut that has a sunken roof. That’s Uncle’s house. Stay there for the night. No need for a map.

I feel we’re in great danger of falling off the face of the earth. Going to sleep will be the best thing. And that’s just what I do, listening to the cars speeding along, I gaze out the window at green meadows, brown hills, blue sky until I become hypnotized by the groaning of the engine and the scent of rubber tires, with many daydreams about the Texas cowboys I expect to see soon. Mom fusses about not being able to see the road as if she’s driving for Daddy.

In the night I wake to Mom shouting, “Stop, Daddy.” Yes, she calls him Daddy too. She’s much younger than him. “Stop!” She yells louder. When I sit up to look, I can see nothing but the headlights beaming into the black sky that surrounds us. In front, half of a white fence and nothing on the other side but stars. There could have been a sign that said “CLIFF” – but like I said my father can’t read and neither can I.

“It’s a dead end,” my older sister yells. We’re inches from going over the edge of a mountain. I can’t breathe.

We had missed a turn at the river or at a mountain, or the road with the falling house where Uncle once lived twenty years ago. Whatever the instructions, landmarks invisible in the bewitching hours of the night don’t warn us that we’re falling off the face of the earth. I force myself back to sleep. I pray into the car seat for a miracle.

In the early evening after crossing the hot desert without air conditioning, we stop for gas at Mobil. Daddy recognizes the red winged Pegasus – or the flying red horse, as it appears to me. He says one word to the gas station owner. “Ethyl,” instead of “Gas, please.” Ethyl, for ethanol, is one precise word and he must have wanted the attendant to know that he knew a fancy word for gas. He says it with dignity, a human dignity denied him in America. I hang my head out of the car and breathe in the smell of gas. I’m intoxicated. I feel free because we’re going somewhere as opposed to being stuck on a block, in a city, in a state, or in a country that doesn’t want us. Dizzy from the fumes of gasoline, I fall back into the seat, enjoying the feeling of floating.

We can’t sleep on the side of the road for risk of being arrested. And we can’t get a motel room because of being black. Daddy has to make it to our destination in two days and one night without sleep and without another driver. I wonder what vacation amenities my classmates might be enjoying.

GUNATILLAKE: Does Zenju’s story of injustice remind you of a time when you’ve faced injustice or disadvantage in your own life? If it feels safe, bring that time to mind, and breathe.

EARTHLYN MANUEL: “Are we in Texas?” Please let us be in Texas. A few hundred miles later Mom announces that we’ve arrived. It’s near 100 degrees of humidity. The earth has turned away from the sun and the orange tint lands on a landscape of dirt, rocks and tufts of dried grass. There’s a saloon standing alone. No horses hitched to a pole, and no white cowboys parading about dressed with holsters like on TV.

Daddy gets out of the car as if he has just driven across town to a place he knows. Or maybe he’s bracing himself for the relatives he hasn’t seen since he was a young man. Has their hair turned gray and white like the hair on his head that he colors with black dye? Will they recognize him? He stands for a long time near the car waiting and looking. He adjusts his Stetson, dusts his Florsheims, and straightens his slacks. He never wears his work shoes out in public. He’s always dressed. Always a display of pride.

I jump to the ground into a pile of dirt. I hadn’t done the packing so I was without my cowboy boots, hat, and holster with its cap gun. As we walk closer to the saloon, loud laughter, and the smell of liquor, sails towards us.

We walk towards the saloon with Daddy in the lead. “Come on,” he says. “Let’s meet your cousins.” We enter. The noise hits me first. Grown men and women cackling in a dark red lit room, bent over a bar with drinks clinking with ice cubes. Then a yell, “Cousin Tela! He made it!” Someone yells. I imagine sometimes folks don’t make it, because my father is not the only black Creole person that can’t read English.

I stand still while the cousins grab and hug my parents. My father is 64 years old and my mother is 47 at the time. No cowboys. No horses. And our cousins are old enough to be our parents. I’m stunned. I’m disappointed. Us girls are pushed through from one cousin to the next, receiving booze scented-kisses.

My sisters and I are laid to rest in the back of the bar. We can hear Daddy’s people mumbling in Creole. Cigar smoke trails in to fill the holes in the walls that are so close to my nose I can feel the heat of the night coming through them.

Our morning is filled with more landmarks to reach Opelousas, Louisiana: Go past the house without the roof. Turn left at the post office and go past the meadow with the cows. When you see the fork in the road go straight or else you’ll end up on the wrong side of the train tracks.

When we arrive within a day, I look up into the dark wide face of Auntie Ola, the place marker that said we were from Louisiana, even though we were born in California. She’s the marker that confirms the shaping of our image into the land on which my father and mother were born. She’s the one who holds the same memories as Daddy. Even with a full glass of the sweetest cow milk ever, I can’t take my eyes off this coal black woman with soft black hair, who is Louisiana herself – and I belong to her.

I fall in love with this aunt whose very life holds us in the red dirt, etches our names in the wood of her house when she speaks to them, marks our place like in a chapter of a book, where the story with my father in it had stopped when he left. “Go play,” she says. She has few words like my father. Why are black people so loud about some things and quiet about others? They don’t say the important things around us children. It makes me uncomfortable because black people are always in danger. Maybe they’re quiet so they can hear someone running up behind them.

Two younger boy cousins, who Auntie Ola didn’t give birth to, take my sisters and I for a walk down the road that lasts us five minutes. We run from the cows that our cousins parade around and introduce to us as if they were pet dogs. Mom, Ola, Daddy, and Auntie Ola’s old man, laugh so hard when they see us panting at the door. Maybe we’re not shaped exactly like them after all.

Ola Manuel’s house sits up on stilts on an acre of land. Her dog runs under the house when we charge from the cow that never makes a move. She smiles like Daddy. And it isn’t long before I realize her smile is my own.

That night I see my parents together in their underwear for the first time in my life. I close my eyes. They are human. They are a man and a woman. And Texas and Louisiana are as naked as them. I can’t let it go. There are no cowboys, no holsters, and no boots like my own, only cows with big heads and big eyes.

Auntie Ola died eight years later. The place she marked for us in Opelousas became the end of a book. The story of the Manuels living in Louisiana was over. Like on the back of a book an author’s picture appears, there was one of Ola in her casket stuffed in my father’s drawer. I nearly fainted when he showed it to us on his return from yet another car trip to Louisiana to her funeral. It was 1965. I’d sneak sometimes to look at my dead aunt in her casket. I shivered each time at the image that would remain my last memory of our first and last summer vacation. Oh, and I never told my classmates the truth about not seeing cowboys.

What I did see was courage, trust, and joy all wrapped up inside my parents. These were the qualities I would have to hone in my life to live fully in my dark skin. I bow to them.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: There were so many elements to Zenju’s story: The universal experience of being on a family road trip; the tragic experience of what it is to be discriminated against in the country of your birth; being a child in an adult’s world.

And for our meditation together I’d like to bring out three themes which most enveloped me when listening. And the first is heat. What is the temperature of the space around you like right now? Is the temperature causing you discomfort? Or is it pleasurable? Something in the middle? Or are you not sure? The sensation of temperature on our skin. The junction between what we call the outside world and what we call ourselves. Feel the temperature. Breathe with the temperature.

Are there any parts of your body which feel particularly hot? Your head, your chest, your shoulders, your belly even. Let them be hot. And if uncomfortable, see if instead of that heat being something you have to push away, see if you can perceive that heat as energy and power. Soothing even. Warming the body. Relaxing the body. Radiating.

The second theme that struck me during Zenju’s story was silence. The silence of her parents. The silence of the drive. And now that she is a Zen Priest, the silence that is her ground of being. Here’s ten seconds of silence.

What did your mind do during that time? How did it deal with the void, the fullness of silence? Now here’s 20 seconds of silence.

Isn’t it interesting how we struggle with silence. The mind full of momentum, always with some comment or convincing storyline. So for this next period of silence, see if you can relax into it and just listen. Letting the silence pervade you, energize you. And if it makes sense, listen to its sound.

The third theme that Zenju’s story brought up for me is appreciation. Her appreciation of her parents’ courage, their trust, their joy. Her appreciation for the experiences that made her, and continue to make her.

So let’s close this meditation together with appreciation. Bringing to mind someone whose qualities have touched you and inspired you to follow in their heart’s footsteps. Smiling. Feeling the warmth of their image in your mind. Enjoying the silence together. And as you do, I’ll bring you to mind, appreciating you for taking this time to be with us.