One envelope at a time

It starts like a game, like hide-and-seek or a treasure hunt: letters, scribbled on paper napkins, sneakily placed at the bottom of bags. Where will the next one be? For author Hannah Brencher, letter writing is a family tradition. Notes are slipped along with lunches, bright turquoise envelopes regularly tossed in the mail. But after a family death, Hannah’s letters with her mom take on a new tone and a new meaning. And the act of letter writing itself changes forever.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

One envelope at a time

HANNAH BRENCHER: It’s in this letter, and the letters that keep coming that Fall where I meet someone who isn’t just my mother anymore. She isn’t just a caretaker or a person to call on a bad day. She isn’t just an emergency contact. Somehow we’ve crossed borders and boundaries and we’re becoming friends. Real friends. This is new territory.

It’s as if we knew the possibility always existed but, for the first time, we’re jiggling the doorknob and allowing ourselves to walk in this space, my mother leading me still. We give one another advice, acting as sounding boards; we send one another jokes, and letters, and packages. I watch her – and coach her from the sidelines.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Hannah Brencher is the founder of More Love Letters, an organization that helps people connect through the age-old art form of words handwritten on a page. In today’s episode, Hannah shares a story about deepening relationships when we slow down enough to express ourselves with pen and paper.

In this series we blend immersive, first-person stories with mindfulness prompts to help you restore yourself at any time of the day. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide on this episode of Meditative Story. From time to time, we’ll pause the story ever so briefly for me to come in with guidance to enhance your experience as you listen. I hope these prompts will be helpful to you.

And before we hear from Hannah, I’d like you to smile. Ultimately all of her work is about connection and joy, even in difficult circumstances. So even if you don’t feel like smiling, give it a go. And notice any change in mood that follows as a result.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

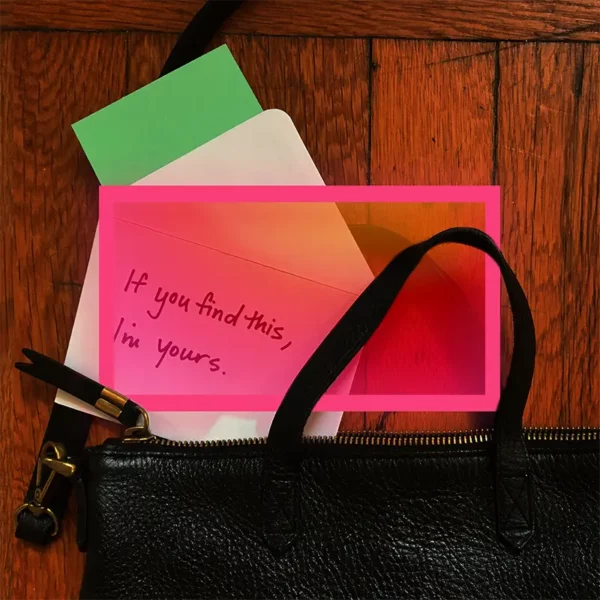

BRENCHER: It starts out as a game. A hide-and-seek of sorts. My mother scribbles love letters on paper napkins and sneakily places them in the bottom of my bright red lunch bag. Her memos to me, her daughter. Her reminders hidden in the mundane of daily life that someone, somewhere is sending light and love.

These letters, always hidden somewhere for me to find, come from my family’s long and winding lineage of letter writers. My grandmother passed the tradition down to my mother. My mother passed the tradition to me, one adorned envelope at a time. And I’m planning to pass the tradition forward one day in the form of notebook paper that carries the scent of home. Even if all the postmen disappear, we will still have these letters, written on scraps of paper.

It’s on a day when my family’s forest green SUV is packed up with Tupperware bins and bright blue IKEA bags that I finally understand why I need those letters from my mother. Why I want these letters to keep coming to my new home in Worcester, Massachusetts as we drive the 2 hours and 43 minutes there. A 10-by-10 dorm room with paper thin walls.

I’m 18 and I wear big, bug-eye sunglasses the whole day, even though the sun never comes out. I don’t want my parents to see that I’m holding back tears. I know this. The moment almost all of us work up to, where we go off on our own and forge a new path, without anyone holding our hands. But I want five more minutes to just be small and in the protection of the people who leave the kitchen light on for me every time I come home.

The summer leading up to going off to college is different than I imagined. My mother spends her best hours in a hospital room, sitting beside her mother who is slowly forgetting who she is. My mother’s summer smells of chalky blue hospital gloves as she tries to figure out how to mother her mother through the last part of the story.

My father tells me the call will come soon. The one where I have to come home and bury my grandmother. Two weeks into that first semester, I pack a small bag full of black clothing and wait for my brother to pull up to my dorm. I get into his blue truck. We barely speak the same 2 hour and 43 minute drive back home to attend my grandmother’s funeral.

When the casket is lowered into the ground, and the bagpipes play “Danny Boy” one last time, and the leftover finger foods are stored in ziplock baggies and placed in the fridge, my father drops me back off at my dorm room. I allow the chaos of new courses and new activities to sweep me up and make me forget the loss back home. Meanwhile my mother and her sisters go through piles of notebooks and letters from my grandmother. Her soft but abrupt handwriting was everywhere. She kept notebooks and journals and logs of books she’d read up until her memory began to fade.

One afternoon in that first semester, I take a trip to the campus post office to check for mail. I love this trip. The long walk through the hills of the campus and now, since it’s October, I can watch the leaves change from a youthful green to a crimson red. Slowly but steadily, the Autumn is coming in and bidding the leaves to break off from the only thing they’ve ever known. This is the one time death has ever looked this beautiful and necessary to me.

I enter the small post office. I turn the corner to find my box. It’s at eye-level. I fidget with the lock: Right. Left. Full circle right. Full stop. 34. 8. 24.

I jingle the lock and watch the small box open up. It’s a letter from home. My mother’s familiar handwriting, thin and spreading out on the page like it’s in no hurry to be tidy or proper, cascades across the envelope. The envelope is a bright turquoise color. I know this is not the original envelope. I’m a rule follower. I buy the card with the envelope assigned to it. Not my mother. She picks the brightest envelopes she can find. Deep purples. Sunflower yellow. A regal blue. Anything but plain white.

GUNATILLAKE: What colors can you see around you? Do they feel bright and sharp? Or dull and flat? And even if you have your eyes closed, what’s here to be seen?

BRENCHER: I don’t carry the letter back to my dorm room. I open the envelope immediately. I stand in the small post office, surrounded by students coming in and out of the space wearing backpacks and throwing the pizza coupons they’ve received in the trash, as I unfold the piece of notebook paper that came from a spiral bound notebook.

It’s funny how letters can transport you. They can lift you out from the space you’re in and put you right beside that person who’s writing to you, from their corner of the world. In the letter, my mother attempts to spell out her grief in short sentences and unkempt cursive. I can feel the pain on the page, echoing off of her swooping “y”s and lanky capital letters. This is the first time she’s dancing with real grief.

In the letter she tells me how she’s crying these days. She tries to hide the tears from others. She wants to be strong but nothing is the same after you lose your mother. She’s surprised to find the world is still moving forward. People are still calling. People are going to work. The world just keeps spinning but she’s trapped. She can’t go on pushing her cart through the grocery store, surveying the different types of shampoo for a worthy sale, when her entire insides quake with her mother’s absence.

“I am spitting these days and I am finding it helps,” my mother writes to me. “I am spitting on the bathroom floor and it feels so freeing.” I don’t know who this woman is. She’s not the strong woman I’ve always seen. I picture her standing in the middle of the pink bathroom and hocking loogies onto the pink tiled floor. There she finds release for the pain. She finds an outlet for her grief.

It’s in this letter – and the letters that keep coming that Fall – where I meet someone who isn’t just my mother anymore. She isn’t just a caretaker or a person to call on a bad day. She isn’t just an emergency contact. Somehow we’ve crossed borders and boundaries and we’re becoming friends. Real friends.

This is new territory. It’s as if we knew the possibility always existed but, for the first time, we’re jiggling the doorknob and allowing ourselves to walk in this space, my mother leading me still. We give one another advice, acting as sounding boards. We send one another jokes, and letters, and packages. I watch her – and coach her from the sidelines.

She picks up her mother’s memories and moves forward with only the ones she wants to keep – not the chalky blue hospital gloves or the sound of machines beeping. Not the long days in that stale hospital bed. She keeps the moments when her mother was vibrant and healthy, just as she would want to be remembered.

Even though everything in my life at this point is texts and emails, I write to my mother. I pull out the paper. I embrace the sloppy handwriting that takes up two lines. I share stories with her, and I buy stamps, and I watch my words be tossed into a mail bin. The man in blue will get these notes to my mother who is 2 hours and 43 minutes away. Because of those letters, she feels close. This is a sacred part of adulthood I never asked for. I never knew I needed it. But one day, I hope my daughter and I cross over the same threshold. I hope she jiggles the doorknob and enters into the same space where my mother led me.

When I’m 26, I’m doing my best to brave a severe depression that feels like a winter that’s lasting too long. I put on my coat and boots, take the car keys, and drive down to the drugstore, one of the only places still open on Christmas Eve. In the cards and notebook aisle, I pick up a two-pack of black composition books, faux leather and edgy in appearance. I buy a pack of silver Sharpies. I carry the supplies home in a flimsy plastic bag, take them up to my room, the plastic wrap encasing them.

There, I begin to write letters to my one-day daughter.

My daughter doesn’t exist yet but, just because you’ve never met someone doesn’t mean you can’t see them in your mind, as real as ever. I see her springy ringlets, bright auburn hair, fiery locks that come from both sides of our families. Lanky in frame with pale freckles down her arms, she laughs like her daddy and she excavates her life for goodness and delight, like her mama.

I haven’t held her yet and our hearts have scarcely met, but I’ve been writing her letters for years.

I call my writings to her “fight songs” because they don’t look like the words in my own diary. They are braver. Pulsing off the page, full of potential, reminding her that one day, more than likely, she’ll find herself at a crossroads in the story. She’ll have to decide how she plans to fight for her life. Will she be gutsy and brave or will she cloak herself in words of doubt and frailty? I beg her to pick up the anthems and run towards the light.

From this point forward, I fight through the depression with new purpose. I am no longer clawing my way out of the deep, dark woods for myself. I am stitching a better ending, a more reliable roadmap, for a one-day daughter who finds herself stuck in the deep, dark woods years down the line.

GUNATILLAKE: What does this exercise of Hannah’s bring up for you? Interest? Judgment? If you were to do the same and imagine someone in your future lineage, who would it be and what would you tell them?

BRENCHER: My iPhone pings. Another reminder pops up. As much as I try to find a quiet moment, there is always something demanded of me.

All these technological rhythms are embedded in my day and yet what do they prove? They’re not tangible. I can’t hold the texts I send close to my chest and trace them for a scent. The digital footprint – as mammoth as it may be – isn’t proof that you and I were here. That we lived. That we loved. That we danced in the kitchen to no music at all, or that we held someone’s hand or made them a cup of herbal tea when their world came crashing down around them.

But I still have the proof. In scraps of notebook paper. In folded cards from my mother. In cards from my husband, sneakily tucked inside of a book I’m devouring while my head is turned. These things – the feeling of them against my fingertips or the sight of them stacked in a cigar box – are the proof to me that I was here. That she was here. That he was here. That we all showed up and tried to live with all the guts we could. That we rejoiced. That we cried the salty tears and spat on the bathroom floors. That we never forgot the way it felt to go to the mailbox and find a personal piece of someone waiting for you.

It’s the letters, tattered, and worn, and losing their ink in some places, that I’ll keep holding onto. I’ll hold them tight and keep them safe. Hold them tighter when grief stands in the doorway and asks to go another round. Even tighter when the night is thick and the darkness feels endless and I need a hand to hold onto. I’ll keep holding them tight – tighter and tighter – and extra tight when the day comes, the day when I can no longer hold you.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Listening to Hannah, what really struck me was just how many similarities there are between the act, the art of letter writing and that of meditation.

Both start with intention, with heart. Then that intention, through thought, turns into action, into movement, the movement of the hand, marks on a page. Those marks are now an object – a representation of our inner experience, our inner life – now outside. That journey, taking our inner experience which we feel so personally and making it an object, something we can observe outside of ourselves and reflect upon is the journey of meditation. And it’s a journey, a movement which can be so freeing. And better still, shared with others.

So, wherever you are, however you are, take a moment. Breathe. Smile. Let go of any tension you might have in your body. Do whatever you need to be soft and open.

And if you were to write someone a letter based on how you’re feeling having heard Hannah’s story, inspired by it even, moved by it, who would that be? Bring them to mind. Let the thought of them bring joy if it’s here, and if there’s warmth in the mind, let there be warmth. Feel it.

So. Writing the letter of this moment, a letter in response to Hannah’s story, what would you want to share? What feelings, what moods, what emotions can you name? What can you name, commit to paper, turn into something for another to discover?

And if you were to write the letter of this moment, the story of this moment, how would your body express your feelings? Or in other words, what would your handwriting be like? Would it be angular, full of tension? Would it be soft and round, open and playful. Would there be capital letters? What does sadness look like on the page?

The letter written, now imagine your special person receiving it, moved to be hearing from you – and in such a personal way. Sensing that image, sensing into it. And make the intention that when you recall listening to this episode, and you have the time, of writing your own letter and releasing it out into the world.

Hannah spoke, quite beautifully, of her letters as proof that she was here. That the people who wrote them were here. Even if now they’re not.

As I stand here, recording these words for you, I am here. I know it because I feel my feet on the floor. I see my engineer Ben in the studio here in Glasgow through the glass, and his little wave makes me smile. And I feel the smile as a lifting of my face and a softening of my belly.

You’re here too. Separated in time and space, but here at the same time. There’s a real magic to that. At least I like to think so, and I hope that you do too.