Release the expectations that limit you

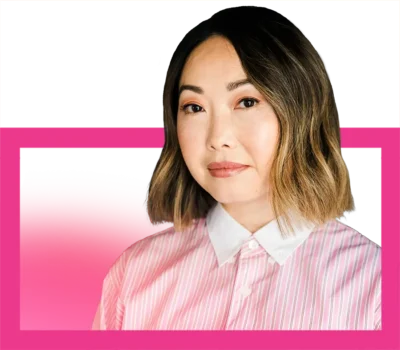

Lulu Wang, writer-director of The Farewell, grows up in a family where the expectations for her future are clear: she’s destined to become a piano prodigy, and she must be grateful for the sacrifices her parents have made to give her that opportunity. In today’s episode, Lulu tells the story of how she finally finds her own space away from those expectations, and in doing so, unlocks the joy of making her own discoveries.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Release the expectations that limit you

LULU WANG: I continue moving through the crowd, and my gaze lands on a magician in a bowler hat, showing his card tricks to a kid. The kid watches, amused, but the magician’s not smiling. I lift my camera to my eye. He looks right back at me. It’s like a moment of confrontation. Him, seeing me, seeing him. I capture it.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Lulu Wang is the acclaimed writer-director of the film The Farewell and the new must-see limited series Expats. In today’s episode, Lulu shares the story of how she grows up in a family with rigid expectations for her future as a skilled pianist. It’s only when Lulu finds space away from those expectations that she realizes there is unbridled joy in having the freedom to make our own discoveries.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open, your mind open, meeting the world.

WANG: I follow my mom into the large wood-paneled room. We pass by empty folding chairs set up for Bible Study later in the week. My family isn’t really religious, but I guess when you move to America, you start going to church. The fellowship hall is quiet. It’s a weekday, and there’s no service today.

I take a seat at the old wooden piano at the back of the hall. We can’t afford a piano of our own, so my mom brings me here to practice.

On one of our first visits, the pastor hands mom a key and says, “Anytime that you guys want to come here so Lulu can use the piano, be our guest.” We haven’t felt such generosity from a stranger since moving to Miami from Beijing a year ago.

I have a complicated relationship with the piano. I start playing when I’m four years old because my mom always wanted to play a musical instrument herself, and never had the chance. Her parents were trying to survive the Cultural Revolution. They didn’t have the privilege to sit around and think, what would be fun for their daughter? My mom constantly reminds me how lucky I am to have this opportunity, but to me, piano just always feels like an obligation.

I place my red John Thompson songbook on the piano’s music stand. In Beijing, my piano teacher would smack my hand with a ruler if my hand position was incorrect. I straighten my posture and start my Czerny finger exercises, playing the same notes, ascending, then descending, over and over. It’s all incredibly boring.

As I play, my muscle memory kicks in. There is something nice about doing something here in Miami that feels so familiar.

Since moving from Beijing, I’ve felt a sense of being foreign that I don’t know how to put into words. I’m used to seeing people that look like me. People who are ahead of me, and I can see my own future in them. But now, nobody really looks like me. It’s hard to picture what the future holds. My parents hold on to what they recognize, and they recognize me playing piano. So that’s what they want me to do.

When I’m done with my warm-ups, I open the songbook and start plucking out the notes to “The Cuckoo.”

My mom sits in one of the folding chairs nearby. This is our bonding time. I go to school all day, and she works at a department store, even though she was the editor at a major literary gazette in Beijing. There’s very little conversation between us about what we’ve felt since moving to America — where we don’t speak the language, where we’re cut off from our family. My parents have made so many sacrifices for us to be here. There are a lot of unsaid feelings. But my mom is more focused on, “You’ve got to keep up this piano thing”. Even if we don’t talk about what’s going on, we still have this time together. She just sits and watches me play, attentively. I mess up a few notes. “Do it again,” she says.

At six years old, I’d rather just be playing and exploring like other kids. I don’t even know what I’m really interested in. No one ever asks me. It makes me restless. But I know how important this is to my parents. And so I keep coming back here every day after school to practice piano. Because I don’t know what else there is. Because that’s what’s expected of me.

A 1920s Chinese mansion fills the giant projector screen. The main character comes into frame. She looks terrified as she watches another woman get dragged away to her execution. I’m eight years old and I don’t think this is a film for kids. It’s dark.

This screening of Raise the Red Lantern, by Zhang Yimou, is being held by the Chinese student organization at the University of Miami. My dad’s a student here. I twist around in my seat and scan the room. It’s packed. Everyone’s captivated. I’m so bored. This is my parents’ world — it’s a Chinese film, not American, not even Chinese American.

I let out a big sigh. “I have to go to the bathroom,” I whisper.

I grab my friend Winnie. She has a bowl cut similar to mine. Together, we run over to the bathroom, and under the fluorescent lights, I look down the line of stalls. I get an idea and my eyes grow wide.

“Watch this,” I tell Winnie. I go into one of the bathroom stalls and slide the lock shut. Then, I get on my hands and knees and crawl into the next stall without unlocking the first door. I do the same thing in the next, and then the next and I ask Winnie to help me. We go down the entire row locking every stall from the inside. This is going to be so funny. I picture everybody coming out of the movie and seeing all the locked doors in the bathroom. I laugh. It may seem unkind. But it’s also kind of hilarious.

I get so tired of doing what’s expected of me. Of naturally falling in line. Sometimes my only answer is mischief.

As I crawl out from under the last stall, I hear Winnie’s mom yelling at her, “What are you doing?” Winnie panics and blurts out, “It was Lulu’s idea.”

The auntie drags me back to my parents. My mom is horrified. She and my dad are raising a classically trained pianist. They want me to be elegant, intellectual, to play Brahms or whatever. Instead, I’m crawling on the dirty student union bathroom floor.

Part of me is always seeking ways to rebel, to not fall in line. Yet my family has already gone through a big disruption, moving so far from home. Part of me deeply fears what will happen if I abandon what’s expected of me.

GUNATILLAKE: When it comes to how you should be, do you also carry the weight of expectations from others? Can you feel the weight of them in the body, feel where they are? What would it be like to let those expectations go, even for a moment?

WANG: The main walkway of the Miami Dade College campus is lined with palm trees. They cast jagged shadows on the white cement. Standing in the bright sun, sweat starts to bead on my forehead. I can’t tell if it’s from the heat or from nerves.

I tug at the hem of my conservative black dress. I feel like I might throw up. I often get this way before piano competitions. It’s the pressure.

I scan the line of other students waiting outside with their parents, ready to perform. Suddenly, a girl rushes out of the building. Tears stream down her face. She runs over to her parents, crying, “I messed up!” My stomach flips. That could be me.

I’m seventeen. I’m a senior at an arts magnet high school. When I get accepted into the program, they tell me that out of all the pianists who auditioned, I’m their first choice. Somehow, other students find out. Now I constantly have to live up to their expectations of me, on top of the pressure I feel from my parents.

“Are you ready?” my dad asks me. I shrug. “I don’t think Peter’s that good,” my mom says. “He got second place last year. If he can get second, you can get first.” I don’t know how to respond. She adds, “You should’ve practiced more.”

Everytime I try telling them that I might not want to play piano anymore, they say what they always do: that I should be more grateful.

I think about the piano that now stands in our living room. It’s German-made, with a very warm sound. My parents saved and saved to buy it for me so I wouldn’t have to practice at the church anymore. It’s their very first big purchase after moving to the US. A huge representation of their sacrifice for me. That sacrifice, and all the expectations that come with it, weigh on me.

The door to the building swings open. A woman with a clipboard steps out and says, “Lulu Wang?” That’s me, I guess, even though that’s not how my name is pronounced, but it was before I started correcting them. I follow her into a big room. Suddenly, I’m freezing. The AC is on full blast after waiting so long in the heat. I walk toward the huge grand piano at the center of the room.

On my left, three judges sit at a table. It’s covered in papers. The score sheets. Each sheet has precise categories, followed by the numbers one to five. I’ll be scored on stylization from one to five, technique from one to five, and so on.

I give the judges what I hope is a confident smile. They expect me to be elegant, to play beautifully.

There’s no sheet music in front of me. I’ve practiced for months and months and months to memorize this piece.

I’ve played it so many times that it’s almost like when you look at a word for too long and it stops making sense. There’s so many notes. What’s the next one? Is the next note an A? What note comes after that? I feel like I’m starting to psych myself out.

I can’t think about it. I have to let it just be muscle memory. I have to just play. My fingers are flying. It’s almost robotic. Regurgitating this music exactly as I’m supposed to play it, exactly as expected.

I make it through the performance. I feel like it’s not my best. When I stand, I give a slight bow to the judges. They smile politely and thank me, but remain poker-faced. I have no idea how I did.

Now that it’s over, I’m relieved, but unsatisfied. Doing well in these competitions depends on excelling at the technical execution of music written over 200 years ago. This devotion to technique means I’m always doing things in a way that’s been done before. There is never any focus on: what do I see? What do I want to say?

As much as I wish I could walk away from piano, I’ve been doing it for so long. It feels silly to stop now. And everyone keeps reinforcing that “you’re really good at it.” It’s as if their expectations for me have become my expectations for myself. I know I should always do well.

If I give up piano, what if I’m no good at anything else? What if I try and fail? I’ll have no one else to blame.

And besides, if I give it up, all of my parents’ sacrifice, my own sacrifice, will be for nothing.

It’s a warm March day. A vibrant parade makes its way through the streets of Boston. The air is filled with loud music and the sound of people cheering. The parade floats are celebratory and boisterous, but my attention is on the people on the sidewalks. The spectators. The vendors.

I see an older woman selling jewelry at a stand. She looks lively, joyful. I cradle my camera. The weight of it feels satisfying in my hands. I peer through the viewfinder at her. The shutter snaps with a soft click.

I’m here on an assignment for my photography class. I’m in my final year at Boston College, where I’m majoring in Music and Literature. I completed all my core requirements, so I figure I’ll try something new. This photography class is an elective. We’ve only just started talking about what makes an image interesting, how to frame it.

I continue moving through the crowd and my gaze lands on a magician in a bowler hat, showing his card tricks to a kid. The kid watches, amused, but the magician’s not smiling. I lift my camera to my eye. He looks right back at me. It’s like a moment of confrontation. Him, seeing me, seeing him. I capture it.

Shooting on film means I won’t see any of the photos until I develop them in the darkroom. So I don’t know if what I’m capturing is good or bad. There is nothing for me to compare myself to. No one is doing the same thing. It’s freeing. I focus on what I’m seeing. I learn to recognize what I’m seeing, without judgment. I’m in this moment.

The darkroom is another place for discovery. It’s where I find myself working alone at night, long after the rest of campus has fallen quiet.

I mix chemicals in the sink and then process my negatives in trays on the wide counter. I stare at the print in my tray and suddenly, there’s this person staring right back at me. The magician, caught in the middle of a card trick as the young boy watches him. One by one, I hang my photographs to dry.

Time seems to stop when I’m in that darkroom, embraced by the red light and the pungent metallic smell of the chemicals. While I wait, I curiously glance at other students’ photos — each with their own distinctive style and perspective.

Then I inspect a few of my own photos drying on the line. Details start to reveal themselves that I don’t remember seeing earlier in the day. The texture of a sidewalk. A foot in the corner of the frame. Someone in the background doing something interesting. I remember the moment, but it was over so fast. And then I kept walking and it was gone. But now, it’s here forever.

No one else is in the darkroom with me, but I feel like I’m surrounded by life. I can almost hear the sounds of the parade, all around me.

There’s a secrecy to being here too, by myself. No one is waiting on the other side of the darkroom to be like,” is it good?” I’m not here to copy anyone. Or to look at sheet music and interpret what somebody wrote 200 years ago. I don’t strive to be judged by fixed criteria. All I’m thinking about is, how do I make these images more interesting? How do I look deeper? It’s liberating.

It’s as if I’m learning how to see for the first time. Working with a camera is not something that’s ever been in my vision or my family’s vision for me. In it, there’s space for my own discoveries.

It’s the most exhilarated I’ve ever felt.

GUNATILLAKE: There is a magic here in the darkroom for Lulu. The magic of being able to do something for its own sake. Is there something, I wonder, that you can do more of in your life, just for its own sake, not because it will fix a problem or because it’s the right thing to do?

WANG: I roll up the sleeves of an oversized button-down shirt that I stole, I mean “borrowed,” from my partner. Over top, I slip on my apron and tug a giant farmer’s hat onto my head. I grab my shovel. With the whole outfit, my brother tells me I look like the gardener emoji.

Stepping into my backyard garden, I tilt my head toward the California sun and breathe in the scent of earth. I walk across the soft grass towards the vegetable patch.

I examine the herb bed first, then the lettuce bed. Looks like it’s zucchini time again — little zucchinis have started popping out. I walk around the trellis at the center of the garden, which rises up from a circle of earth surrounded by stones.

Perennial and native flowers give the garden color: purples, deep burgundies, pops of orange. I breathe in their sweet aroma.

My garden has become my place to feel grounded since my career has gotten busier and busier. I’m 40, and my love of photography has turned into a love of filmmaking. I write and direct film and television. My work is improvisational, intuitive. Now when I express something through my art that someone else recognizes, I feel seen.

Even so, it’s easy to slip into a rigid path. A track. To fall into someone else’s agenda, with someone else’s expectations. The garden reminds me to give myself space to follow my own curiosity.

At first, I just start with a question: Can I grow tomatoes? I get some seeds, I get some bags, I get some soil. And bam, I get tomatoes. It’s incredible. Sun, water, seed… who knew? I mean, I’ve known my whole life that these things combined make plants grow. But I’d never grown anything from a seed. And then it becomes something that I can eat. Each step, each attempt, feels like a discovery. I still find myself blown away. Like magic. The garden reminds me that if I plant the seed, it will grow.

Now, I’ve realized that piano taught me the same thing. With practice, you can get better at anything, whether you like it or not. But it’s definitely more fulfilling when you like it. My parents have come to support my decision not to pursue piano professionally. I have the freedom to come back to it on my own terms. I’m thinking about taking jazz piano lessons, and I might work on a piano score for my next film. There are ways for me to not just play what somebody puts in front of me, but to be part of a process where I’m creating music to help tell a story. There’s so much room for me to make new discoveries there.

When we grow up being told that there’s one way we’re supposed to be, one path that we’re expected to follow, so many avenues for exploration are closed off. But there’s joy in wandering into the unfamiliar, just for the fun of it. To discover something new about ourselves, about people, about the world.

When we find space away from other’s expectations, or even our own expectations, we stumble into the sacred space where we’re free to wander, free to play. We can attune ourselves to what is being asked of us, what can channel through us outside of the limitations of our own imagination. We open ourselves up to the joy of discovery.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Lulu.

Lulu’s a fabulous pianist. But I, like many others, am so grateful that she did wander into the unfamiliar and into film. The Farewell is one of my absolute favorite movies of the past ten years.

It’s Lulu’s initial training in piano that makes her the powerful creative talent that she is today. Because she understands discipline and fundamentals, she can then let go into improvisation, being able, as she puts it, to wander into the unfamiliar.

Most of the time in our closing meditations together, I invite you into the fundamentals, sharing classic techniques and ideas, such as body awareness practices, inquiry, concentration and all the rest. But in honor of Lulu, and it is an honor, we’re going to improvise. Improvise from our existing understanding and experience of mindfulness. For some of us, that will be deep. For others, not so much. It doesn’t matter. We’re going to improvise based on what you know.

And the way we’ll do that is by letting the mind be free.

However your body is right now, letting it be like it is.

The breath, how it is. The posture, how it is. Things, as they are.

And for the rest of this meditation together, we’re going to just let the mind be free.

We’re going to give our mind permission to wander into the unfamiliar, just for the fun of it.

But different to daydreaming, we’re also going to watch it wander.

Letting our attention roam free. And while it roams, we will watch it. Just watching where the mind goes. Watching what is happening now. And being open to whatever comes next. That is all.

Letting the mind go. Letting it do what it wants. And watching it.

Giving the mind freedom.

And watching with awareness.

With interest in what comes next. With the joy of discovery.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. The senses open. The mind open.

And just watching our awareness as it roams.

Watching. Watching the cinema screen of our mind.

Drenched in freedom. Free of expectation. Free of ties.

Noticing any expectations. Even the subtle ones. And loosening those too.

Thank you Lulu. I’m so excited to watch whatever comes next.

And thank you.

I’m excited for you to try this technique again some time by yourself maybe. Watching whatever comes next.

Go well.

We’d love to hear your personal reflections from Lulu’s episode. How did you relate to her story? You can find us on all your social media platforms through our handle @MeditativeStory. Or you can email us at: [email protected].