The beetle and the whale

Nature filmmaker Tom Mustill travels the globe capturing breathtaking footage of animals while highlighting the work of the world’s leading conservationists. But one summer day, on a vacation kayak trip, he comes face to face with nature in a way he never expected. He shares the story of how this rare and terrifying encounter re-sparks his sense of wonder — reminding him to sometimes put down the camera to see the world as it truly is.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

The beetle and the whale

TOM MUSTILL: I know enough about whales to know what to expect from this excursion. We’ll see some whales resting, floating near the surface, a few fleeting glimpses of their bodies as they breathe between dives. But as we paddle out in the fog, something feels different.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Nature filmmaker and writer Tom Mustill has spent much of his career behind the camera, capturing breathtaking footage of animals from around the globe and highlighting the efforts of the world’s leading conservationists. In this week’s episode, Tom shares his unique perspective on the beauty nature has to offer and how a brush with death reminded him of the importance of putting down the camera to see the world as it truly is.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

MUSTILL: I lay on the old green carpet in the basement, playing with my electric train set. The tiny parallel rails glint in the morning sun coming through the windows behind me. My nose twitches from the smell of rubbing alcohol we use to clean the tracks. I lay them out carefully in a wide looping oval.

I then add my finishing touches: small black beetles I’ve gathered from the garden. By my 6-year-old calculations, if I place them on the tracks, the train should run straight over them.

I delicately balance an insect on the metal rail. And I see Dad’s legs come into view. He’s wearing corduroys and leather slippers. I lift my eyes to meet his. I feel as if I’ve been caught in the act.

“Well Thomas,” he says. “You understand that what you are doing is your choice.” He slows down the word, “choice,” letting it land firmly in my head. I’m stunned. He’s not rebuking me, but I feel ashamed.

I’ve always been very interested in non-human animals, but as I look down at the beetle still in my hand — its hair-like legs fluttering to nowhere; its beautiful dull black carapace — I feel like I’m seeing it with new eyes. Until now I had never thought that I had much responsibility towards the existence of other living things. That I had a choice. My father leaves the room. I take the beetles into the garden, and I let them go.

We live in North London, not far from Camden Town. I love playing in the small patch of garden behind our house. It has a lawn. Some medium-sized trees. Toward the back end it gets brambly and overgrown. Today, I pick berries from our redcurrant bush.

I don’t plot to kill insects any more. I observe them through a magnifying glass. Wonder at their varied exoskeletons. The patterns of their wings. The claws on their legs. Once I’ve safely put them back where they came from, I lie on my back and watch the clouds go by. When I turn over, the damp smell of the ground fills my nostrils. I am face to face with the grass, entranced. I look at the blades and through them, feel lost in a minute jungle. I’m not looking for anything in particular. I’m just looking. There’s always something to surprise me. I begin to feel part of a bigger, wider world — and relish every chance to experience it.

GUNATILLAKE: What is a detail of your life that you can notice right now as you listen to this? There will be something. Attention open, and interested in the fine, the subtlety. Taking our chance to experience what is here.

MUSTILL: The winter desert air enters my lungs dry and cold. I’m in Alice Springs, the absolute center of Australia. Everything is red. The soil, the rocks, the sunsets. The kangaroos are red, too. That’s what they’re called: Red Kangaroos. These ones are orphans being reared on a nature reserve. I’m 29 years old and here to film them for a documentary.

A decade ago, I study zoology and work as a field biologist. But I find it lonely and tedious work. The best part is coming home and telling stories about it. Filming wildlife for nature shows on television seems like the best of all worlds. I can tell stories. Educate people on the plight of animals. Share my love of the natural world and the lives of the inspiring people fighting to save it.

I now see the world through a lens. My co-director Andrew and I finish shooting almost everything we need here in Australia: kangaroo babies (called ‘Joeys’) playing, the big males fighting, even kangaroo courtship, and mating. Our remaining task is to capture a wild birth. This is the spectacular moment when the tiny kangaroo newborn the size of a jelly bean emerges from the birth canal, crawls and claws its way up to the top of its mothers pouch on her belly, then disappears inside to nurse for many months. At this time, no-one has ever filmed this before.

The whole birth takes about two minutes, and can happen at any time. So, we follow the pregnant kangaroos for weeks. Waiting. Watching. One day, a female starts behaving erratically. She scratches the ground. Licks the inside of her pouch. Shudders. All signals which suggest we’re close.

The sun’s gone down. The night is freezing. We keep shifting the cameras to where we can see her through the tall yellow grass. We’re exhausted. I’ve got the wide-angle camera. Andrew’s shooting close-up. We practice for this moment for weeks and plan it for almost a year. We can’t miss it. Where is that little jelly bean?

The female puts her tail between her legs and sits down and gets up and falls over and sits down again. The little pink creature is coming out! We’re in the perfect position to watch it wind its way up through her white belly fur. The small lights we have are just enough. It’s dark but beautiful. And then, it’s over. The mother stands, shakes, and hops off, her tiny baby safe inside.

Andrew isn’t celebrating. He turns to me and says, “oh no.” His camera hasn’t worked. We miss the crucial moment we’ve been waiting for. We’re devastated.

Andrew falls into a miserable mood. I’m deeply disappointed too. I imagine the producers asking us if we got the shot and having to tell them “No.”

The thought that I was just witness to a beautiful moment of life creation that so few people get the chance to see barely occurs to me. All I choose to see is that we failed.

The next day, I sit alone with my camera. I watch a mob of kangaroos lounge about, each in their own sandy pit. It turns out this is what they mostly do all day. Sleeping is the heart of kangaroo essence. I get some footage of them napping and then just sort of sit next to them for hours. It’s calming. My feelings of failure fade. But this is not what I’m expected to make a film about.

I understand how nature shows choose to see wildlife. They prioritize brief moments of drama, conflict, and violence, giving the impression that that is what makes up the entirety of an animal’s life. This makes these animals seem unrelatable to us, by only being spectacular.

A mother kangaroo twitches and sniffles in her sleep. Is she dreaming? Her joey wakes up to stick his head out of her pouch, first his snout then each floppy furry ear. I love this. It’s so unexpected and, in a way, beautiful. In these soft, low key moments I see what originally drew me to nature.

I’m eight years old, when I explore the little wood at the end of the garden at my grandfather’s cottage. It’s spring in the Yorkshire dales. Everything feels fresh and lively. I clamber over a toppled down dry stone wall and see a tiny movement at the base of a tree. A mother duck is sitting on her eggs. I freeze, not wanting to disturb her. And I watch. I memorize the details of her feathers, their mottling pattern, the subtle iridescence. I look at her bill, brown and yellow with its black tip. She is perfectly camouflaged against the old leaves. I sit for ages, delighted by this surprise finding. The unexpected wonder and beauty in it. I hold my breath. When it’s time to leave I creep back as quietly as I can.

As a filmmaker, most of my day is spent thinking about my camera and my preconceived ideas of what we need to film.

I’m proud of the films we produce, but they’re impersonal. They’re not what I’m most curious about. What I find notable. If I felt free to represent nature as I experience it, these films are not what I would make.

GUNATILLAKE: What are you most curious about? Our worlds are made in part by where we put our attention, and by our actions.

MUSTILL: It’s 6 a.m. My friend Charlotte and I push our red kayak offshore and paddle out into Monterey Bay off the California Coast. The water is unusually calm. Like a swimming pool. We pass sea otters resting on the surface, holding onto each other. Gulls and pelicans cruise past us. Sea lions snort and sniff. I’ve been on the West coast of the U.S. traveling and visiting friends for a few weeks. My dad passed away in the Spring, and it’s been hard adjusting to a world without the funny, enigmatic man who taught me the power and responsibility of my choices, who taught me so many things. I take this time to reset. Today I have the chance to go sea kayaking during the humpback whale migration. Despite the early hour, a few boats are out already.

It’s been three years since the Kangaroo assignment. I continue to document animals all over the world. I see incredible things. I capture the shots producers want. I’m nominated for an Emmy. I love the work, but part of me still feels disconnected from how I choose to show the world. I’m grateful for this break.

I know enough about whales, to know what to expect from this excursion. We’ll see some whales resting, floating near the surface, a few fleeting glimpses of their bodies as they breathe between dives. But as we paddle out in the fog, something feels…different.

There are so many whales and they are very active. Three surface about 40 yards away. They exhale in unison, blowing out big wet fishy broccoli-smelling breaths, before diving down again. On the horizon we see humpbacks jumping clear out of the glassy surface. We stop paddling. There are whales coming and going from every direction. I’ve never seen this many before. It’s astonishing and a bit intimidating. Part of me wishes I could see it through the safety of my camera.

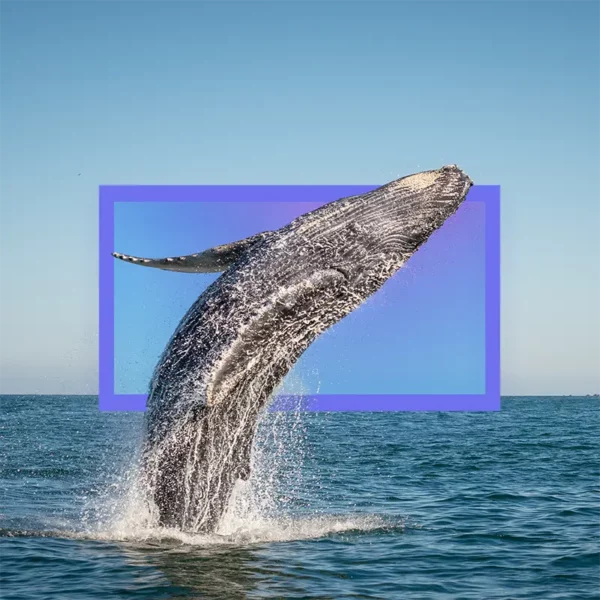

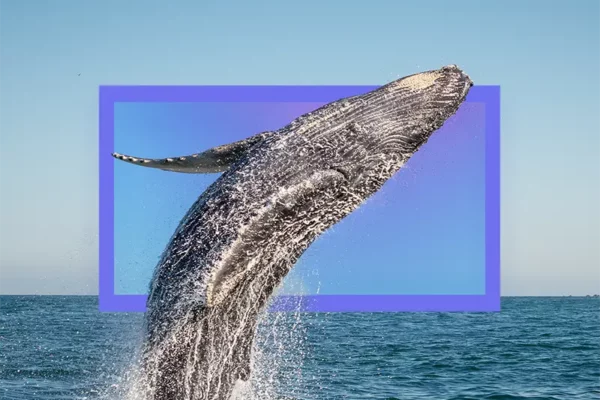

Suddenly, an enormous whale comes out of the water in a full breach straight at our kayak. It’s like a building rising up from the deep. Just unreal: a 30-ton whale is hovering in the air above me. The whale’s body turns, falling directly on top of us. I just have time to think, “Oh, I’m going to die now.”

In a flash I’m underwater. All I see is churning white water surrounded by darkness. It feels like I’m quite deep. I’m thrown around violently. My life jacket then starts pulling me upwards. I swim in that direction. Charlotte must be dead. I’m surprised not to be in loads of pain.

When I surface, I see Charlotte, and she’s going “oh my god, oh my god” and grinning. We’re both totally fine. The tourists in the boat nearby have captured the whole thing on film. Soon it’ll go viral. “British kayakers’ terrifying close encounter with humpback whale.”

I’m left thinking, how am I not dead? There must be something I don’t understand.

I learn later that the whale saw us and turned its body away in mid-flight. This is why we’re not killed. I remember the little boy about to squash the beetles on the train tracks and the words my father said in that moment. The power I realized I had. The choice I had to make about how to use that power. Now, I’m the one that was almost squashed.

But I still have a choice. I survived a rare and terrifying encounter. The question is: What do I do now?

Do I just go back to work? Back to what I was doing before? I can’t. I feel I have a responsibility to this experience.

In the countless press interviews that follow, I realize that this is a chance to help the whales. So I make a documentary about humpbacks. I use our story to tell the story of the whale population of Monterey Bay — of their lives and challenges.

For the first time, I bring my own perspective to my work and make it personal. This is a big change. In nature filmmaking, we work hard to show animals in a world without people. Now, I do the opposite. I weave the worlds of humans and other animals together. I’m led not by what I think a producer or audience might expect, but what I really feel these animals’ lives are like. I put myself into my work, but I don’t make it about myself.

And I start writing about them. It takes me four years to craft my first book. I spend countless nights hammering away at 1:00 a.m. lit by the glow from my laptop screen. Driven by my own sense of curiosity. I put aside all the structure and artifice that stood between me and the natural world. I embrace the mystery and complexity and awe of the world as it is. I choose to embrace it all.

It’s a late summer afternoon in London. The paving slabs of the street glisten with fresh rain. I push a pram containing my 18-month-old daughter, Stella. We’re on the way home from nursery school. Life is busy.

I marvel at Stella’s animal nature: how relentlessly she learns to shuffle, crawl, and walk, how her teeth erupt from her gums, her changing appetite for different foods.

We stroll through the park and I reflect on how recently, my encounter with the whale came full circle. I travel to the Dominican Republic, where I get the opportunity to swim with humpback whales — males singing, calves playing near their mothers. Everyone else there had their cameras ready, waiting to capture the event. I don’t. I let myself just experience the moment, free from prejudging what it should be like, what it will be like, or how I’ll frame it for others. I just experience it. Witness the grace of how their mighty bodies flow, how my body rings with their voices when they sing. And I realize this is the key for me: It’s when I choose to surrender my expectations that I’m so marvelously lost. I encounter things that confound and surprise me.

This shift in perspective may sometimes cost me from shooting the perfect shot, or being the best old school wildlife documentarian, but how it opens me up to see the world is worth it.

I push Stella’s pram around the corner, and I notice colors above us. A rainbow arches over East London. “Look!” I show Stella, pointing. “Rainbow!”

“Wain-bah,” she says, pointing too. This is one of her first words. I love seeing it through her astonished eyes.

A little further along towards the rainbow we pass three ladies chatting. They seem stressed out. They clear a path for us. “Rainbow!” says Stella.

They pause and look up. “OOHHHH,” they exclaim. “How lovely! Thank you so much. What a beautiful rainbow.” It is a particularly beautiful rainbow. Vivid against the light blue sky.

We keep going, all the while Stella saying “Rainbow! Rainbow!” It generates smiles all around, especially from me. She keeps my sense of curiosity fresh. Like I’m seeing the world anew. She reaches for a flower — “flo-wah.” At first she pulls at it, ripping its petals. “Gently” I say, and I smell the flower. She leans in and carefully kisses the flower. She reminds me of my responsibility towards this life to find wonder in it. And just like my father did for me, I hope to show her the power of choice.

It’s not always easy to take a step back and breathe, to see the beauty right in front of us. We all have our work and worries, lists of preoccupations. We all have a lens through which we see the world, that can block or distort our view. But we also have the power of choice. The choice to lay aside our preconceptions, of what we think is expected of us, and embrace the awe-inspiring world that surrounds us. To find joy in something as small as a beetle, as big as a whale. The beauty and mystery is there, if we choose to see it.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Tom, so much.

I think a lot about how much attention rules our world. Yes on the macro level, how media drives so much of how power works nowadays, but more importantly in the context of Tom’s story on the very human scale.

I love that bit with Tom’s little daughter Stella, who is not that much younger than my own. Stella’s attention is drawn to the rainbow, and she delights in it. Others whose minds were elsewhere have their worlds entirely changed when their attention is pointed to the rainbow and Stella’s contagious delight.

This relationship, between our attention and our moment-to-moment experience, is central to the mindfulness tradition.

And when you really boil it down, all meditation is, is actively deciding, actively choosing where you put your attention. So meditation, it’s a game of choices and attention.

So for our closing meditation today inspired by, and I hope in conversation with Tom’s story, we’ll play with the theme of choices and attention.

But to start, let’s choose to slow down.

It’s likely been a busy day, and your choice to invest your attention on listening to this show is a way you look after yourself. It’s a sign that you’re on your side. So let’s appreciate that. We certainly do.

A way I love to slow down is to do something I’m already doing but a tiny bit slower. So tiny a change that no one else would notice but you.

So if you’re walking, you can choose to drop your pace just a sliver.

If you’re not moving, you might choose to take an ever so slightly longer out breath.

Give it a go. Let’s choose to slow down. Playing around with whatever feels right for you in your situation.

Choosing to slow down.

So, as we talked about before, meditation is in its essence, choosing to place our attention in a certain way. And today we’ll explore four dimensions of that, and the first is why.

The choice of why.

Why do we choose to put our attention where we do? That is a very general question. If we are being more direct, let’s ask this one: Why do we meditate? What are the qualities within ourselves that we want to grow?

Rest with that question for a little, and sense your answer.

Knowing the reason you choose to meditate, to cultivate your attention can be really helpful. Another word for it is intention. And when we know our intention, it can act as a compass, reminding us of where we want to get to, keeping us on track.

The next choice about our attention is what, what will we pay attention to. Or to be more technical: what will be our meditation object?

This choice matters a lot. Because the nature of the object affects our attention, our awareness. And indeed, our awareness can affect the object. I like to think they are in a bit of a dance.

For example we could choose the breath as our object. Classic! But what aspect of the breath we choose will alter our awareness and therefore our experience.

So we could get subtle, and choose to pay attention to the sensations where the breath meets the nostrils. It’s subtle and quiet, but if we are able to rest our awareness there, then that awareness will adjust to be as subtle and delicate as its object. The downside is that the more subtle or finer the object, the more likely it is that we’ll lose our grip and spin out into distractions.

So as a counter to that, you might choose a simpler sensation, such as the contact of your feet on the ground. It’s easier to land on which is great, and while not very subtle at first, can over time become subtle as the awareness settles down.

So now you’ve got your why, make your choice about the what. Choose your object, the “what” you’re going to pay attention to, and do it.

The next choice we’re going to make is how. How do you place our attention? Do we place it lightly or tightly?

Hold something too tightly, and we can get tired and tense, just as if we were to hold something in our hand super tightly. But hold it too lightly, and it just won’t stay. So that’s the balance when it comes to how.

Choosing to hold our object in our awareness not too tightly but not too lightly. Supporting it with our awareness, like we might hold a butterfly in the palm of our hand.

Our fourth and final choice about how we use our attention is slightly different to the others so far. It’s the choice of who.

With body calm and mind calm. With breath, soft. And heart, open.

We choose who is paying attention. Who is paying attention? A response might naturally come up. I am paying attention, me.

So, again.

With body, calm. And breath, calm. With heart, soft. And mind, open.

Who is paying attention? What is the choice? Is there a choice?

There’s a glimmer of mystery in that question. And mystery was something that featured so much for me in Tom’s story. The mystery of what can emerge when we are present with the world around us. And get out of the way a little bit making space for the magical.

So thank you Tom for reminding me of that.

And thank you.

We’d love to hear your personal reflections from Tom’s episode. How did you relate to his story? You can find us on all your social media platforms through our handle @meditativestory, Or you can email us at: [email protected].