Learning resilience from earth’s edge

“Cape Spear always calls me back.” Tony Tjan grows up in the cold and dramatic landscape of Newfoundland, where snow piles high and storms rage – but the neighbors always keep a door open to help one another. Returning home for a visit as an adult, he recalls childhood stories of abundance and adaptation, as he and his family learn to love this life on the Easternmost point of North America – in the place where the sun strikes first.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Learning resilience from earth’s edge

TONY TJAN: There are pictures of me as a baby wrapped in this big coat as she pulls me on a toboggan through the snow down our street in the middle of winter. Both of us look equally astounded by the white world around us.

My mom cries a lot in those first few months. Their illegal basement rental doesn’t have its own bathroom. The ceilings are low. The heat doesn’t work well.

But they are fortunate. Neighbors teach them the local ways telling them how to keep the car engine warm, and very often we’d get a friend or a patient of dad’s dropping off some freshly caught fish right off the line, or some baked goods that were still warm. On this windy, barren “rock,” neighbors have always had a history of looking out for each other. There’s a Newfoundland saying that people leave their doors ajar even in a storm. We depend on that open kindness. We still do.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Tony Tjan is treasured for bringing humanity and character into business. As the CEO and co-founder of the Boston-based venture investment firm Cue Ball – he sees making money is just one dimension of success. The founders Tony stands behind are proving that the highest performing businesses – the ones that endure the test of time – are the ones led by good people who build their company’s culture around good values.

In today’s Meditative Story, Tony takes us to the end of the earth – the dramatic, wind-swept island of Newfoundland in far-eastern Canada – where the forces of nature and people have shaped his views about investing in purpose-driven people. And in full disclosure, Cue Ball is an investor in the organization behind Meditative Story, and Tony personally has been a bright light in giving the support and encouragement that makes this podcast possible.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed, the body breathing, your senses open, your mind open, meeting the world.

TJAN: I make my way through the last leg of a winding road flanked by weathering pine trees on both sides. They gradually thin out as I approach my destination.

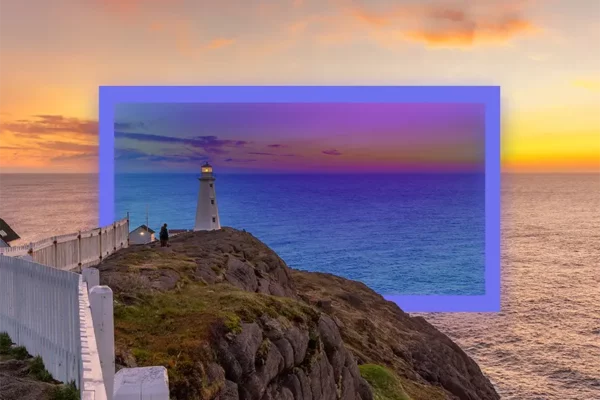

I’m 29 years old, and it’s Mother’s Day weekend. I’m back home to visit my parents in my hometown of Newfoundland. But before seeing them, I make my pilgrimage to Cape Spear – the very first place each morning where the rising sun kisses the edge of North America.

It’s just six miles from my childhood home. Yet, it feels like the end of the world, and if it isn’t, you sure feel like it is.

I tend to visit Cape Spear on more windswept days or on very early mornings before anyone arrives.

And today, it’s only me.

I look up to the wooden steps to the iconic lighthouse that still precariously hangs at the cliff’s edge. As I begin my walk up the steps, the smell of Newfoundland’s salt air and wet fog washes over me, and it welcomes me home.

I stretch out my arms, and it is an expansive feeling.

On one side, all of North America’s land unrolls before me. On the other, the Atlantic Ocean as far as I can see.

I let myself take in the cadence and crescendo of the ice-cold waves that pound incessantly against the face of those cliffs. I’ve seen large chunks of icebergs carried by the North Atlantic’s whiplash currents crash violently in here, breaking apart like a blown-up asteroid on a video game. Yet for some reason, despite those jarring cliffs, the rising octaves of angry waves and the swirling winds that can howl and squeal, this place lures me into a sense of calm and a reflective respite that I rarely experience in the frenetic pace of my entrepreneurial life in Boston.

This is a place of contrasts. As rough and foreboding as those cliffs seem, they are equally stoic crags standing strong and guarding tall like frontline soldiers protecting entry onto the continent.

But I also feel like they’re guarding me.

And as much as the winds howl, they always eventually recede into a quiet whisper – whistling their final tune into cracks and crevices that become home to the final breath of their last secrets.

I am reminded of EJ Pratt’s poem “Newfoundland” that he wrote while growing up here in the 1800s.

“Here the winds blow,

And here they die,

Not with that wild, exotic rage

That vainly sweeps untrodden shores,

But with familiar breath

Holding a partnership with life.”

My best childhood tool is the plastic bucket. In Newfoundland a bucket comes in handy more often than you might think.

When I am 9 years old, my father finally takes me out to the low tide at Middle Cove Beach. Even though it’s late June, it’s still cool. Like most people gathered on the beach, I’m wearing a thick fisherman’s knit sweater underneath my windbreaker jacket.

“Hello there Dr. Tjan,” says an old man with a beard. “How’s it going? Here with your son, are you?”

The beach is pretty crowded with people that day, holding their buckets and cheap fishing nets they bought from the local hardware store. I hold a bright green plastic beach bucket and a doubled-up set of plastic garbage bags.

I grip my father’s arm and we walk in our slippery boots over the smooth beach rocks out into a shallow part in the mouth of the bay. And then as we wait and look ahead – seemingly out of nowhere – the waters grow dark as a glittery mass encroaches. It’s like a giant amoeba.

If you didn’t know any better, you’d run away. But the darkness drawing closer isn’t some scary monster – it’s the sea, literally filling herself with fish.

And as the fish come into shore, they act like an assembled living plow pushing the water to either side. It’s almost as if it is an illusion but it is real. Displaced right before my eyes is the ocean’s water with the overflow of silvery little fish. Capelin.

I can’t move. I look down at my knee-high rubber boots and see thousands of capelin swimming and slipping and teeming all around my feet and between my ankles, almost making me fall over.

This is Newfoundland’s famous capelin roll, when the small fish migrate to the low tide to lay eggs. I’ve never seen it up close before, and it blows my mind.

I squint at the sky and notice the seagulls who are watching in delight the whole show from above, singing, and diving to catch their share. We are all here, at the edge of the continent witnessing and experiencing the web of incredible life force.

I press my garbage bags into the water. Dozens of fish careen into the bag within seconds.

I shout with an indescribable glee as I watch the capelin swim into my poor man’s fishing net.

The arrival of the capelin feels like it is something much more than an annual tradition or even more than a natural phenomenon – it not only feels like magic it is magic. And it makes me feel like anything is possible.

GUNATILLAKE: Nature can be like this. A spectacle so extraordinary, it points us to the magical. An enormous school of fish, a mesmerizing flock of birds. What miracle of the natural world, big or small, makes that connection for you? Go there now in your mind and in your body. There’s plenty of time.

TJAN: Not long after the capelin roll, it’s blueberry season. Serious business. We’re gathering our fruit reserve for the whole year, and my sister and I are critical laborers for several days in a row.

This time my bucket is white, a large leftover ice cream tub from the local creamery. The plastic sounds deep and hollow when I tap on its bottom.

My grandmother has moved in with us from Indonesia. She has never seen blueberries before and spends all day picking with us these little spheres of indigo fruit.

The birds sing in the full summer sky and they swirl around in the intoxicating velvet and tart scent that floats in the breeze above our heads. We are filling our buckets on a rocky ledge where a thousand years ago, the Vikings might have very well picked fruit from these same patches.

The berries are small but juicy. It takes a lot of restraint to pick fresh blueberries and not eat them right then and there. My mother reminds us, “In the buckets please, or you won’t get any pie.”

While mom and dad don’t talk too much about their past, it is on family outings like this that are my best chance to hear little bits of the story of how my parents moved to a place so different from their home country.

Born as overseas Chinese in Indonesia, both my parents leave their birthplace to escape the discrimination and often bloody persecution against resident Chinese in Indonesia at that time by going to college in Taiwan, and deciding to leave their large families behind.

After medical school, my father learns that the government in Canada is hiring doctors, and it might be possible to get a visa to stay there. The trip to Canada not only requires his financial savings but takes two nights and three days: Taipei to Tokyo, Tokyo to Hawaii, Hawaii to San Francisco, San Francisco to Vancouver, Vancouver to Saskatchewan, Saskatchewan to Montreal, Montreal to Halifax, Halifax to Gander, Gander to St. John’s Newfoundland.

As an intern, Dad moves into a medical dormitory. It’s 1966. The locals call this rugged island “the Rock.” It looks like another planet to him. Nothing at all like the dense humidity, tropical climate, and throngs of people in Indonesia or the modern cityscape of Taiwan. He stares out his dormitory window into the dark Newfoundland night. Thick white crystals fall against the cold glass. He’s never seen snow before. He goes outside to touch it for himself. A snow christening, he calls it. He stays up the entire night, not wanting to look away.

About two years later mom would make it over to Newfoundland to meet dad.

There are pictures of me as a baby wrapped in a big coat as she pulls me on a toboggan through the snow down our street in the middle of winter. Both of us look equally astounded by the white world around us.

She’s gone from living with 10 siblings in Sumatra to Taipei and now to harsh winters, few culturally familiar faces on a rugged fishing island in the North Atlantic.

Mom cries a lot those first few months. Their illegal basement rental doesn’t have its own bathroom. The ceilings are low. The heat doesn’t work well.

But they are fortunate. Neighbors teach them the local ways telling them how to keep the car engine warm. What kinds of boots they should buy, and very often we’d get a friend or a patient of dad’s dropping off some freshly caught fish right off the line, vegetables just pulled from their garden, or some baked goods that were still warm. On this windy, barren “rock,” neighbors have always had a history of looking out for each other. There’s a Newfoundland saying that people leave their doors ajar even in a storm. We depend on that open kindness. We still do.

The locals teach my mom how to make blueberry pie and crack open a lobster. She cooks the lobster with long green onions, ginger, and garlic plus Chinese bean paste and soy sauce. That dish alongside many of her culinary improvisations soon become the talk of the town, along with her holiday parties and traditional Chinese dance lessons. After a first winter of isolation, Mom becomes not just a social worker for her profession but somewhat of a socialite traversing across the culture and traditions of her past and the locals customs from blueberry festivals to singing carolers called mummers to debates on who has the best local fish and chips.

In my earliest years growing up, we rarely speak English at home. I don’t think too much about it until I am ready to go to school.

The fluorescent lights of the basement classroom beat down on me as I stare at the color chart leaning against the dusty green chalkboard. It’s my first day of preschool.

My teacher explains we will be reciting colors out loud this morning. An icebreaker to meet one another. Rows upon rows of different colored circles in reds, blues, yellows, greens, and purples taunt me as I try to figure out which color is going to land on me.

I want to be just like my classmates. I want to fit in. But when my turn comes to say the color that the teacher is pointing her stick at – all I can think of is “Huang Ze” – or yellow in Mandarin. After an awkward pause, I sputter out the English word with a broken accent. I feel the shame of tears on my cheeks. I don’t want to be different.

I relay the incident to my mom when I get home from school.

“Don’t worry. Your English will come quickly,” she says, in Chinese enveloping me at the same time into a big hug.

“Look at me, look how easily I learned English. Remember we’re all here to help one another.”

But to respect our elders and remember our heritage, we continue to speak Chinese at home.

GUNATILLAKE: Honoring the past with its language and culture and food but bright and open to the future. All of time somehow all together. Enjoy this moment, with the breath, the body, the mind how it is. Allowing your experience now to influence what comes next.

TJAN: That late afternoon, I dutifully operate the cassette deck as my mom teaches Chinese dance lessons to the neighbors in the basement. I fast forward to the right song, press the big triangle “play” button, and watch everyone twirl around in yellow silk scarves on our worn green basement shag carpet. Afterwards, she makes us all one of her signature yet paradoxical feasts.

While our neighbors grow turnips, tomatoes, and potatoes, our backyard garden grows Chinese snow peas, bok choy, and Napa cabbage. I have equal cravings for a good feed of fish and chips at our local joint and mom’s steamed chicken drumsticks with Chinese mushrooms over rice and light soy sauce. Always ending with one of her desserts like blueberry sponge cake. That night we have it all!

I graduate from working the cassette player and picking blueberries to other odd jobs. I clean grave lots, help with renovations at my piano teacher’s house, silk screen t-shirts, and I collect quarters out of apartment laundry machines on the weekend. My favorite though is the paper route I share with a childhood friend.

During the winter, we put on our Kodiak steel toe boots and double up on our layers to brave the cold weather. We each have our own black, ink-stained canvas bag full of newspapers. Probably 30 pounds each. We throw the bags over our scrawny shoulders and set out into the snow to start the door-to-door slug.

It’s often frigid cold. On the worst days the snow is up to our knees or even higher. We peak around the corners and side of every house we pass to see if someone’s doing laundry where there might be steam coming out of that dryer vent. When we’re lucky, we hustle over to the vent and take our gloves off. The steam envelopes and saturates our hands and gives us the warmth we need to keep doing our job. It’s what we call our “paperboy’s delight.”

When I am 15, a family friend invites me to stay with them over the summer on the Mainland. Before they even finish with their offer to my parents and without even asking, I say yes.

Even though we’re surrounded by endless water in Newfoundland, I yearn for a larger pond.

Many years later, sitting in a class at Harvard Business School, I listen to a famous professor describe the most successful entrepreneurs. “Real entrepreneurship is the relentless pursuit of opportunity without regard to resources at hand.” He paces the classroom as he talks about well-known entrepreneurs who represent this gritty optimism to scratch up the wall no matter what the odds are.

But my mind doesn’t go to those business leaders. It shoots back to my parents, back to The Rock. We make due with what we have, and when we come together, it feels like abundance. I think of my buckets, full from the bounty of the land and the sea, the feeling that anyone can make something from very little as long as they have an underlying purpose and the patience and will to realize its potential. It’s what drives me to be an entrepreneur.

Yet, we are all entrepreneurs in the narrative of life, and perhaps the truest entrepreneurs are the immigrants, and the single parents, and the frontline workers improvising to save people’s lives and yes the Newfoundland fishermen and women on those icy waters before the light of each day. It is often that we find ourselves striving for opportunity without regard to resource.

For the first time I realize it is not despite Newfoundland, but because of it, that I am who I am. A father, husband, entrepreneur, and human capitalist. A proud Chinese Indonesian Newfoundlander.

Cape Spear always calls me back. I look towards the set of wooden steps that lead up to that iconic lighthouse, precariously perched at that cliff’s edge.

I decide to climb to the top before heading to see my parents.

It’s a viciously windy day. I feel an increasing gale pressing against my back, sweeping me, almost lifting me upward like a hand pushing me. I think of how the crashing icebergs and the capelin and the cod and the whales are the only things between me and the coast of Ireland thousands of miles to the east. I feel both small and individual, and yet large and universal – connected to something infinite. The seas, my community, my clan, all of it.

I climb up the stairs, steadying myself with each careful step.

The gale-force wind whips even harder at the back of my neck. I decide it’s best to turn around. I cling with both hands gripping to the railing even more tightly as I start making my descent.

But in that moment, I realize what I can do. I decide to let go.

I release my hands, face the wind, and lean my torso and body downward like I’m launching off a ski jump. The wind catches me and, for a brief second, time stops.

As I float on top of the wind, I feel it all. What’s made me who I am. All of the resiliency I’ve learned from this place. The pride that is my strength and my weakness.

And so the poem closes…

“And the story is told

Of human veins and pulses,

Of eternal pathways of fire,

Of dreams that survive the night,

Of doors held ajar in storms.”

I am at the edge of the world – arms outstretched, completely suspended by the invisible wind, herself. She cradles me and doesn’t let me fall.

I am home.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you, Tony.

For our closing meditation together I want to play with the theme of abundance that came across so strongly in Tony’s story.

The abundance of Tony’s family life. The abundance of the sea. The abundance of faith and trust as it holds a human in the wind.

So many of us come to mindfulness meditation because we feel like something is not here. We’re not sleeping well. We’re too stressed. And all the rest.

With that mindset we then start working to build the qualities we don’t yet have.

But another way to approach meditation is via abundance. To know what qualities we already have and to look to encourage them even more. To grow them.

In fact, in the early Buddhist tradition meditation wasn’t actually a word that existed, it’s more of a modern invention. The word that was used is bhavana which means cultivation or growing. I love that.

So let’s do some bhavana, some growing, and framed through abundance.

So, let the body be comfortable. Dropping any holding that might be here. And the holding that remains, being cool with it, it’s OK.

OK. So let’s recognize what is already here. Leaving tension aside for now and scanning the body to see if there are any areas which feel either pleasant or just relaxed.

Scanning from the top of your head to your feet, looking for relaxation.

Finding relaxation in the area around your face and jaw as you smile. Finding relaxation in the softness of the belly. Finding relaxation in the rhythm of your chest as it breathes.

There’s no right answer, as long as you are able to check-in with a sense of relaxation somewhere in the body. And if nothing really stands out as pleasant or relaxed, then finding an area of no-tension, a part of the body where you might not feel much at all, like a blank canvas.

Got it? Good.

Keeping your attention in that area of the body and allowing yourself to really feel it. Soaking your attention into that part of the body like water soaking into a sponge. Allowing yourself to feel the pleasant feeling, the relaxation, the area of no-tension as fully as you can.

Let’s make this the basis of our abundance. And open out our awareness to also include the area around here. Letting the pleasant sensation grow. To overflow into other parts of the body, even the whole body.

Once our buckets are overflowing, we spread our blankets and picnic among the bushes and the fuzzy bees. Appreciate what is here to be enjoyed and guarding it, cultivating the conditions for growth.

Dropping the need to grasp for that which is not here. And trusting in our natural qualities. They will hold us up when we lean on them.

Tony in the wind.

Thank you, and stay safe.