Where the water takes me

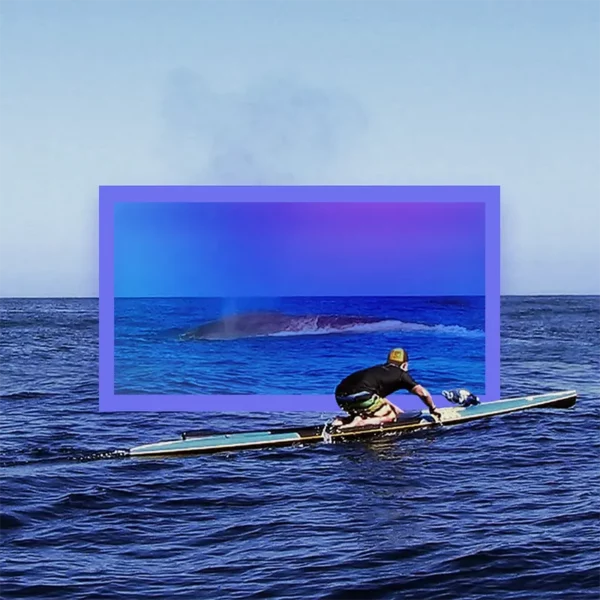

Twenty-four long miles into a grueling paddleboard competition, photographer Donald Miralle sights the buoy that tells him he’s just a few miles from home. But what should offer a sense of relief provokes a feeling of dread. His body shuts down, his muscles refuse to work, his motivation dwindles. With nothing left to summon, he is desperate to quit. That’s when Donald spots a shadow in the water: a massive, majestic blue whale, serenely passing beneath his board. The rare sighting inspires awe in Donald, and an acceptance of forces beyond his control — the wind, the waves, the tide and the whale. With restored confidence, Donald moves through his fear by leaning into the training that has prepared him for moments like this. And makes his way to shore. Photo credit: Dold Miralle, Brandon Magnus.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Where the water takes me

DONALD MIRALLE: I’m meant to be right here. This isn’t an accident. And the only thing holding me back is my fear, this deep-rooted fear that has plagued me for long enough. It has played in the background of my life like a haunting melody: fear of losing. Fear of being a loser. Fear of losing others. Fear of losing things that matter. Fear of losing control. I know this fear. I refuse to let it rule me, or try to protect me, or keep me from where I know I can go. I can do this, I tell myself. I’ve done it before.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Donald Miralle is one of the most respected sports photographers working today. He is the recipient of more than forty international awards. Confronted with a painful loss at a young age, Donald sought solace in the water, where he often felt more comfortable and confident than he did on land. In today’s Meditative Story, Donald takes us to that place of great meaning and healing for him – he takes us out into the ocean, where, after a life of training, he is prepared to handle any situation.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

MIRALLE: The sun shines brightly over the cold, deep blue water. My goggles are secure, suctioned over my eyes. My toes curl over the edge of the starting block. I’m poised. I wait for the gun.

The pool sits at the center of campus in downtown LA, 15-foot walls of red-brown brick matching the style and shade of the 19th-century brick buildings that surround us. I feel safe, completely blocked off from the rest of the campus, from the city, the world – from everything I’ve been going through at home.

I take a deep breath. The gun fires. I spring forward. My body hits the water. My eyes meet the thick black line at the bottom of the pool. Now there’s only the race. My goggles are like horse blinders, blocking out everything but what is right in front of me. Tunnel vision. Alert, ultra-aware.

I feel weightless, as though I’m pushing through the air. My sight is limited. I smell nothing. I feel only the water. All I hear is the roaring of the water rushing by my ears. I know my speed by the volume of that roar. I let go. I let my body do the work – and my mind get out of the way.

The grief, the worries, the baggage I carry, vanish. I move fluidly. I know these strokes by heart. I’ve done so many laps, put in so much yardage, that I just enter the zone.

One day my mother disappears. She’s missing for a full week before she’s found dead. It’s like a bomb goes off, it just shatters my world. I’m 16. This is a defining moment for me. From this point on there is a before and an after.

The sadness, the loneliness, the rage – these emotions consume me. The only way to cope is to harness all that energy, channel it rather than store it. I become hyper-focused and motivated in a way I’ve never been before. I get into mental and physical shape. I develop a kind of fortitude I’ve never had. Until this point I am a competitive but mediocre swimmer.

Every time I get into the water, my thoughts, my sorrows, my baggage are all left on the pool deck. And I know they’ll be there waiting for me when I climb out. So I spend as much time as I can in that pool. The more time and energy I invest, the more I see myself grow.

It doesn’t happen overnight. At first it’s hard to see how all these pieces come together – the repetitions, the practices, refining my strokes, regulating my breath – until I perform.

GUNATILLAKE: Let’s be with Donald as he swims. His breath steady and rhythmic. Supporting his strokes. Supporting his power. Notice the rhythm of your own breath as it cycles. Feel its power.

MIRALLE: It’s December now – my first swim meet in three months, since my mother passed away. My time drops considerably. I’m suffused with a new self-esteem. I’ve got this, I say to myself. I can do this.

That arc of improvement continues through the winter, spring, and into summer. And by junior year my times drop, precipitously.

All this work lifts me out of an emotional hole, carries me through and transcends the pain I am in. It brings me to catharsis. I have enabled my body to perform at a level I only dreamed of but never thought possible. But my body can now do what I believe it was born to do: excel.

My strokes are fluid. The rhythms of my arms hitting the water are steady and consistent. I imagine myself as an open container, a hole where my head is. I picture all the water flushing through my body, washing away the darkness, the negativity, and the pain. Being in the water cleanses me. It transforms me. When I come out of the water, I feel new. I feel reborn.

In just two years I go from being an okay swimmer to a high school All-American headed to UCLA. I become part of the NCAA champion men’s swim program training under an Olympic coach.

My father passes away. And about nine months later, my first son is born. It’s been 10 years since I graduated from UCLA. I have a successful career in photography. I’m married. I’m now a father myself.

I need an outlet. And once again I find myself drawn to the water. I try swimming for a while but it’s not the same. I’m older and I don’t want to race. I need a new challenge.

When I discover paddleboarding, I know it immediately: this is it. Just me, out in the ocean, a mile or two off the coast, nobody around. It’s this total zen place where I’m connected with nature. Dolphins, whales, sharks.

Up above the water, on the surface, I can see everything around me. The sun beats down on my neck. I smell the salt water. I travel four or five times faster than if I’m swimming.

I never know what will come at me, what new challenges, what limits I’ll push up against. I’m at the mercy of the ebb and flow of the ocean’s tide. Just like I’m at the mercy of events in my life.

Losing my mother when I was 16. Losing my father in my 30s. These are catastrophic moments. Until you lose a parent, you can’t know how you’ll handle it. There is no playbook. Some people shut down, get stuck emotionally. Others descend into addiction, depression – which is easier than you might think.

I find that by acknowledging these forces that are beyond my control, allowing them in – absorbing them – rather than fighting against them, I can keep moving ahead. I’m ready and able to adapt and accept and grow in ways I never thought possible.

The tide pushes or pulls, the wind tugs and nudges, the water swells, rushes, rises, and retreats. I have no choice: I have to go where the ocean takes me. But the thing is, out here on a paddleboard I learn to use that to my advantage.

My first time on the board I paddle six miles. It takes me nearly 90 minutes. Hands down the most painful physical experience ever, my shoulders and arms hurt, my neck hurts. But I know what is called for: action.

What I have learned from the deaths of my parents is that there are no emotional solutions to my emotional traumas. I channel my pain and harness that energy. I move forward, and sure enough, it gets easier.

GUNATILLAKE: Can you imagine Donald on his paddleboard? Can you take on some of that strength in your own posture? Your chest open and soft. Your spine alert yet relaxed.

MIRALLE: I’m competing in a race called the Catalina Classic. It’s a 32-mile race from Catalina to Manhattan Beach. They call this the granddaddy of all paddleboard races. It takes anywhere from five to nine hours to complete the race, depending on who you are and what the conditions are. I’m at the mercy of swells, currents, and winds.

Twenty miles into the race, I spot the R10 buoy in the distance, about four miles away. This is the marker I’ve been waiting for, the confirmation that I am 8 miles away from the finish. The red buoy bobs up and down in the water. This will be my target for the next hour. My arms are on fire as I paddle closer and closer. Its white stripes become more vivid as I paddle towards it.

“Oh, shit,” I think to myself as I hit the buoy. “I made it. I’m here… But I am totally exhausted.”

On one hand I’m thinking, I only have 8 miles left! On the other hand, I still have 8 miles left. I dread these will be the worst miles of my life. I’m bonking. That’s the term for what happens when your body stalls. Loses steam. Hits the wall. Hard.

My hamstrings cramp. My groin muscles cramp. My triceps quit. I’m not absorbing the water and salt anymore. My arms can’t move. My whole body is in revolt. I can actually feel it deteriorating. I cannot summon the strength to move any further. My mind races, pinging back and forth between thoughts. All I can think about is the people I’ve lost: My mother. My father. My father-in-law. I’m thinking of all these things and I’m starting to doubt myself.

“Why the hell am I doing this? Why, why am I here right now?” And I’m not just questioning the race, but like … everything. I’m just out here. All by myself. Why?

I cave inwards, collapse in on myself like a crushed soda can. My tank is totally empty. I don’t know how to go on. I can’t.

That’s when I notice a dark shape moving in the water. It’s coming closer. I feel the stillness of the open-air encasing me. All is quiet. I sit still on the board.

It’s a whale, coming right at me. A beautiful blue whale, probably 60 feet or so. It does not deter its line. Before I can even brace myself, it crosses about a foot under me. I hover over him. I’m so close I can see the barnacles on his back. I can see the texture of his smooth skin, inches away, I feel like a fly on the back of an elephant. I feel so small, so insignificant but, at the very same time, so connected to everything underneath me. He surfaces a few feet on the other side of me for a breath and then vanishes, in an instant.

I’m meant to be in this moment. I mean, what are the chances that this whale would cross my path? That this massive, peaceful animal might rise from the depths to greet me – it’s like seeing a shooting star, a magical thing. Here I’m looking inwards, everything crunching in. And this gorgeous rare creature’s presence makes me look back out again.

I’m meant to be right here. This isn’t an accident. And the only thing holding me back is my fear. This deep-rooted fear that has plagued me for long enough. It has played in the background of my life like a haunting melody. Fear of losing, fear of being a loser, fear of losing others, fear of losing things that matter, fear of losing control.

I know this fear. I refuse to let it rule me, or try to protect me, or keep me from where I know I can go. I can do this, I tell myself. I’ve done it before. I repeat it to myself. I can do this. I can do this. These next eight miles – the ones I was so unsure of a few minutes ago – they become the easiest eight miles of my life.

Nearly two hours later I cross the finish line at the Manhattan Beach Pier. I’m third out of a hundred people. When I get to shore, I learn I’m the only one who has seen the whale.

There are immovable events that happen in life. They happen, and they’re catastrophically emotional. They’re like an avalanche and everything just comes crumbling down. Losing someone is one of those things. You have no control over it.

When I’m out on the ocean – sitting in the middle of a rushing channel on my board with water moving all around me – I know I can handle any situation. I move with the tide. I move with the wind. I move with the water. I go where the water tells me to go. I’m at its mercy. Just like I’m at the mercy of these events in my life. The catastrophic ones and the good ones.

I‘m not in control of what happens to me – but I am in control of my responses. On the water, I use the elements to my advantage. I can’t stop the currents. Those are forces beyond my control. I can’t redirect the wind or talk a wave down to size. Whatever wave that arrives … well, that’s the one I get. And that’s the one I ride. I’m ready.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Donald’s story about meeting the blue whale while out racing on his paddleboard reminds me of moments in my own meditation practice. When we exert effort and think we have had enough, a shift in gear, a change of plane, can reveal something unexpected, something magical – but exactly the thing we need to experience in that moment.

As with Donald, it’s not something we can really engineer but this shift is something we can practice so that when it’s available, we’re more likely to pay attention, to notice the whale in the first place. Because as in the story out of all the racers, only Donald did. So let’s give it a go.

You’ll be glad to know I’m not going to ask you to paddle board, but I do want you to make some effort. In particular to rest your attention in one place. And the place we’ll choose is where your body meets the ground. If you’re standing or walking that’s the sensations of your feet on the ground. The contact there. If you’re lying down that’s the feeling of where your body meets your mattress or floor. And if sitting that’s your seat on your chair. Take a little while to find that sensation, the connection of your body with the ground, your bed or your chair.

Feel the simplicity of this. Enjoy any quiet pleasure that might be here.

And these sensations of contact can be quite slippery, deceptively ordinary, without the charge or the hookiness of plans or thoughts or judgements, without the noise of stronger sensations in the body. So as a result, your mind will drift away into the more familiar patterns of thought and distraction. That’s ok. The work here that I’m inviting you into is that whenever you notice your mind slipping away, or has slipped away, be ok with it and just drop it back into the sensations of your body meeting the ground. The sensations of groundedness.

Feel contact. Make the intention to keep your mind here. When you notice drift. Bring it back. Over and over. It’s ok. The mind will drift. Our job is to inject effort, determination even, to bring it back each time.

Knowing the contact with the earth, wherever you feel it the most. Making it the most important thing in the world. Containing the mind here. And returning it again and again, when it slips. Stroke after stroke.

Now drop it. Drop the emphasis on that contact point and let the mind be free. And know what it is called to. Watch your mind move to what it wants to. It probably won’t be a whale breaking the water but there will be something. Know it – however mundane and small it might seem – and be with it with as much openness, wonder even, as you can access right now.

Be so close to the experience you can see the barnacles on its back, the texture in its skin.

Be Donald on his board.

Thank you for spending your time here, it means a lot to us. The wellbeing of our listeners, the wellbeing of you, is so much on our mind as we make this show, especially at this time.

Take care and go well.