The secret to aging well

A California native, Chip Conley grew up visiting the towering redwoods and indulging his curiosity about wise and aging things. But as an adult pioneering a boutique hotel company, he begins to feel the weight of middle age and loses the curiosity that once drove him to innovate and explore. In his story, Chip shares the journey that led him to founding the Modern Elder Academy and how he learned to embrace his own aging and appreciate the wisdom of the elders in his life.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

The secret to aging well

CHIP CONLEY: There’s a particular cactus I like to walk to. It’s an old cardon. It’s gangly. It’s so old that it barely has spines on it, and, here’s the thing: the ones it has are soft, not spiky. I reach my hand out. I want to touch this old cactus. I pet the soft spines, feeling the tickle in my palm. I step in closer. I stretch my arms around the trunk, and I wonder about all it has seen in its long life.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Chip Conley knew from an early age that feeling curiosity and wonder makes life worth living. But, by the time he reaches middle age, Chip is running the treadmill of obligations, exhaustion, and stress that dog so many of us. In this week’s episode, Chip shares how reconnecting to curiosity opens us to sensing the wonder of the world and not just the weight of it. And how this is the secret to aging well.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories, breathtaking music, and mindfulness prompts so that we may see our lives reflected back to us in other people’s stories. And that can lead to improvements in our own inner lives.

From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

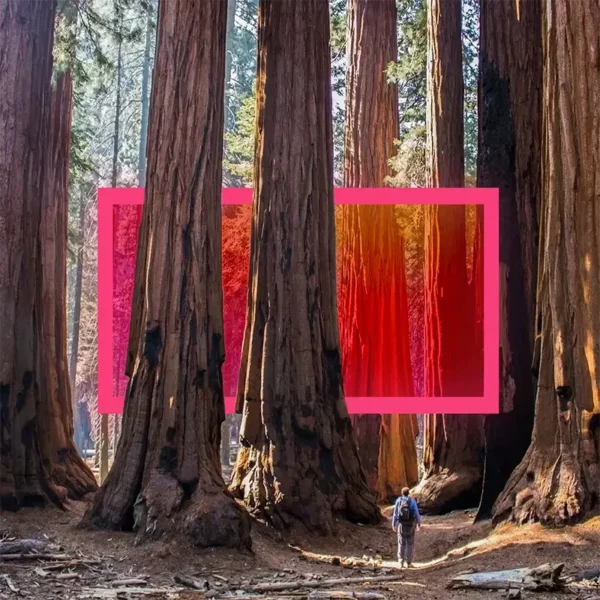

CONLEY: I take off down a wide dirt path through the redwoods. My lungs fill with moist, piney air. It’s mostly shadows in here, but spotlights of sun land on feathery emerald-green ferns on either side of the path.

I’m surrounded by impossibly tall trees. I step off the trail onto fallen leaves and needles and twigs. I wonder how soon they’ll become soil. I have the sense of stepping on something that’s in the process of changing. It all feels soft under my sneakers.

I’m 10 years old. On vacation with my family in Muir Woods in Northern California. It’s unlike anything I’ve ever experienced.

I stop in front of a tree that’s as wide as our station wagon. A redwood. I look up. And up. The top of the tree is so far away, I can’t see it from here. The dark rich redness of the creased bark just keeps going. I reach my palm out. It feels rough and irregularly shaped. But also very soft. It feels alive.

I step in closer, and spread my skinny arms outward. They don’t even begin to feel the curve of this giant ancient creature. I’m hugging the tree. I close my eyes and breathe in. I smell spice and earth and honey. This tree, so sturdy, so humble. What has it seen in all these centuries? What nourished a tiny seed to grow this big? I see how stately and gracious it is in its age.

I turn to my parents with a curious look and I ask: “Why do trees live so long and humans don’t?” They smile and share a little laugh between themselves. But they don’t have an answer.

I hold my grandmother’s hand as we walk down the road lined with market stalls. The street is paved with polished red bricks. I see boxes and boxes of vegetables and all kinds of stuff hanging above the stalls: straw hats, blankets, Day of the Dead skulls. This is Olvera Street, the Mexican marketplace in Downtown Los Angeles. It’s fun. It feels like another country. It’s hard to believe I’m in the same city I woke up in.

My grandmother, Nonni, likes to take me on little field trips like this. She picks me up at our house in suburban Long Beach and drives to the far corners of Los Angeles. Just the two of us. She’s not like my other grandparents, who can be a little stuffy and don’t smile a lot. Nonni’s traveled the world. She talks to strangers. She asks questions. She’s interested in everything.

Nonni stops to squeeze some dark green avocados. It’s like she’s listening to them. The sun shines off her quaffed gray hair. She wears a simple dress, comfortable shoes. When we come to the crates of tomatoes, her eyes light up. There are so many different kinds. I thought all tomatoes were red, but these are purple, and yellow, and orange — some as big as my hand.

When she reaches for one, I shake my head. Grandma knows I don’t like tomatoes, but she’s not having any of this. “How could you not love tomatoes? You’re a Californian!” She’s teasing me, but she’s also serious. “Let’s try some different ones.”

We sit on a bench, and Nonni arranges a salad with five or six different kinds of tomatoes. Cherries, romas, heirlooms … I’m skeptical, but I take a bite of a cherry tomato. Oval and firm and deep red. It explodes in my mouth, and makes me laugh. Nonni is looking at me — there’s a sparkle in her eyes. They’re the same translucent blue as a swimming pool.

I move my tongue against the roof of my mouth. I actually like the taste. I’m still not sure about the texture. But Nonni’s given me a new experience.

I never feel judged by her. She knows I’m a unique kid, my head always in a book, imaginary friends to play with. Yet with her, I feel safe and sheltered. I feel a sense of possibility.

At this moment, eating tomatoes on Olvera Street, I’m not thinking much about growing old. But years from now, when I think of Nonni — her sparkling eyes, her curiosity and her wisdom — it will give me some hope about aging. Being in her presence is like standing before that ancient Redwood. She’s an enlightened witness to the magic and wonder of the world.

GUNATILLAKE: Hearing about Nonni, does anyone come to mind from your life who embodies curiosity and wonder? Someone who helps you or helped you try new things, to look again with fresh eyes. With them in mind, explore what you can do right now — maybe in your body or in attitude, to be more open to magic.

CONLEY: “Chip?” says our president. “Chip?” She looks at me across the conference table. “We need to decide which hotels to put into foreclosure.”

Oy … please not this one, I think.

I’m sitting in the conference room on the top floor of the Hotel Vitale in San Francisco. Outside the huge plate glass window I see an extraordinary view: the white clock tower of the Ferry Building. The sparkling, expansive blue water of the Bay. And beyond that, the distant Berkeley hills.

This hotel is the most treasured piece of the company I’ve worked so hard to build over the past 20 plus years. I’m 48 and wondering if I’m about to lose it all.

The 2008 Recession hit our business hard. We’re looking at bankruptcy. Our beautiful hotels — the ones I poured my best ideas and energy and love into — they may go into foreclosure. I feel ashamed.

I draw my gaze away from the window and look flatly at the advisors seated around me. Three men and one woman. Words are coming from a speaker phone at the center of the table. They belong to a bankruptcy attorney. I can’t focus on what he’s saying. I’m dissociating. His voice is like the adults in the Charlie Brown cartoon: “Wah-wah-wah mortgage…wah…lenders… wah-wah …overdrawn payroll.”

We have to make dire choices: which assets we lose, which employees we let go. It’s like saying farewell to a family member, knowing you’ll never connect again. I feel emotionally jumbled and totally ill-equipped to handle this.

I named the company Joie de Vivre — in honor of my grandmother’s spirit. I launch it with the sense of wonder I learned from her. I try to capture that and give it to others.

But there’s none of that in this room right now. I’m just trying to survive.

I’ve been miserable for a while, even without the financial free-fall. I spend all my time thinking about what I can attain, one way or another. I have a deep sense that I’m trapped in the maze of my own mind. That I’ve lost sight of what really matters. Some of my friends are battling severe depression. I feel powerless to help them. Everybody thinks my partner and I are the perfect couple, but we’re not. One day he says to me, “I can’t do this anymore,” and like that, our eight year relationship comes to an end.

I feel alone. I feel exhausted by the marathon of my life. It seems everyone around me is on the same midlife treadmill of obligation. At this age, we’re all accountants of our own losses and gains, our own hopes and dreams. We can’t help but see where we’re coming up short.

I look out the vast window at the perfect blue sky. I almost laugh with the irony of it. A company named joie de vivre, its founder is utterly depleted of all joy and wonder.

Curiosity is the taproot for my creativity and freedom. But the curiosity well has dried up. Somewhere along the way, I learn that curiosity is inefficient, that I can’t afford to follow my curiosity down blind paths when there’s a business to build. I become harder. More prickly. Laser focused on my company, on my strategy, on myself.

Can I learn to discard the things that no longer serve me? Can I reconnect to the people and things that really matter? Can I become curious again?

All I’m feeling is the weight of the world. Can I learn to feel the wonder of the world instead?

I enter the Gospel music tent from the south side. I think it will feel good to leave the sizzling New Orleans sun. But as I walk inside, I’m immediately hit with an intense, airless humidity. It’s rollicking in here, packed with hundreds, maybe thousands of people. All here for the Jazz and Heritage Festival. They’re swaying, and clapping, and smiling. I slowly work my way forward, looking up toward the stage. I see a dozen singers wearing flowing green and black robes. Some with their eyes closed, lifting their voices to heaven.

I love gospel music. I feel the pulse of this tent in my body. My head is nodding to the beat. My knees are pumping. I look around me. It’s been four years since that conference room in San Francisco. I’ve come a long way. But I’m still recovering.

When I have to sell my company at the bottom of the recession, I’m in an awful place. I toil all day and come home to an empty house. I’m lonely. The curiosity is drained out of me, and the joy and the life too. Then, while recovering from an injury, I have an allergic reaction to antibiotics. I collapse, and nearly die. It’s terrifying, but the experience wakes me up. What am I living for? What can I uniquely offer the world? I know I have to go find my purpose.

And so I’m here in New Orleans as part of a yearlong tour of global festivals. I’m in search of Joie de vivre. I feel incredibly lucky to have time and space and privilege to be on the search.

Back in the gospel tent, I make eye contact with a woman nearby. She’s probably in her mid-seventies. She wears her hair coiled in a beehive. Dangling earrings. There’s something about her. She’s a force. She smiles at me and I smile back. We sway in unison along with everyone else for over an hour.

Eventually, the woman turns to me. “Young man,” she says, “are you open to walking me home?”

I laugh. “Of course!” I say. We work our way out of the tent. It’s dark outside. The air feels blessedly cooler.

“I’m Beatrice,” she says in a warm, husky voice. At the first curb, she loops her hand inside my arm. “My family’s been in New Orleans for five generations,” “And I’ve gone to every jazz fest since it started when I was a young woman.”

Her earrings jingle a little with each step through the Seventh Ward. It’s an old Creole neighborhood, still full of life in the early evening. It’s a long walk, maybe 40 minutes. Beatrice is like my tour guide, pointing things out. She waves at a man sitting on his stoop, and then to another. I feel a deep sense of rooted community. It’s like I’m on one of my grandmother’s field trips.

Over the course of my travels, I’m drawn to these small, collective experiences of amazement. My curiosity guides me, and I know that there’s something I’m meant to learn from them. I travel to see whirling dervishes in Turkey, ritual bathings with millions of people in the Ganges, thousands of beautiful ice sculptures in Manchuria. And now, here to the Seventh Ward of New Orleans. In each place, I’m surprised by meaningful connections I find in this shared theater of life.

GUNATILLAKE: As Chip concedes, not all of us can go on such an odyssey of discovery as he does. So how can we find that sense of wonder in the middle of where we are? How about exploring these questions: What else is there to be seen here? How can I have more of a tourist mind in my own life?

CONLEY: Beatrice’s small clapboard house is decked with a hodgepodge pieces of white wood. “I bet you’ll be wanting some of my ice cold sweet tea,” says Beatrice. “Come on in.” Sweet tea sounds awfully good to me.

We walk inside, past a whole wall of framed photos. I study them. Her children, her grandchildren, her great-grandchildren. Beatrice is beaming. “This one still comes over every day to do homework. This one I take to Church and to Bible study.”

She waves me over to a small formica table. More pictures … this time Barack Obama and Martin Luther King, Jr. It’s like I’ve been invited into some sort of sanctuary. She pours the sweet tea into tall glasses. I swirl the cold liquid around in my mouth. It’s so good. I can make out three clear flavors: honey, ginger, and peach. My favorite flavors. I feel… at home. It’s been a long time since I’ve felt this way.

“What were you doing in that gospel tent anyway?” she asks, laughing, and sitting down. She shared her story, and now she wants to know mine. We’re so genuinely curious about each other.

So I tell her about my travels, all the festivals, how I needed this after a hard few years.

I ask, “You know that scene in the Wizard of Oz when Dorothy lands in Oz and all of a sudden the film goes from black and white to technicolor?” “That’s what I’m looking for.”

I tell her about the places and things I’ve seen. How in the Hindu festival Thaipusam, devotees pierce their backs with hooks to pull chariots. Talking about that image now reminds me of my own burdens I haven’t fully unloaded. The devotion I feel to my business. The pain I carry around the loss of my company. The fears about my health that I push down. The kind of burdens that come from lurching through midlife, weighed down by worries and obligations.

Beatrice watches me with curiosity and interest. I have the sense that she wants to see me — to look underneath the surface. That’s what curiosity means. And in this short moment of connection, we are showing each other something of who we are. Beatrice shows me she lives in service to her family and to her community. She has that same patina as my grandmother. She hasn’t grown old; she’s grown whole.

When I finally get up to leave, she takes my head in her big soft hands, and she pulls me to her bosom. It doesn’t feel strange. It feels wonderful.

“Young man,” she says to my 52-year-old self, “God blesses you and God loves you, and you are going to have a good life.” I see the formica table behind her, our empty glasses still on it. I know this image will stay with me. It will remind me to keep my heart on what’s important. On experiences and chance encounters. On staying curious. On not just feeling the weight of the world, but also its wonder.

That’s the secret wisdom that Beatrice holds. Just like my grandmother. Just like the redwoods.

In the years that follow, I help other modern elders understand how to navigate midlife transitions. I become an enlightened witness to life-changing conversations and help people find purpose and joy and brightness. In doing so, I find those things for myself.

These days, my hair is gray, my muscles are smaller, and my steps a little slower. From my house in Mexico, I hear the waves crashing against the beach. Wave after wave, a constant process of becoming. I close my eyes for a moment and just listen.

I’m 62. I don’t carry the same burdens of middle age anymore, but my body has let me know it’s feeling the wear of years. I have cancer. This week I learn it’s spread to my lymph nodes. I have new medications and I can feel them now in my system. They make me moody. I start the day upset, anxious. I feel really, just lost. Listening to the waves, I feel my breath begin to slow. My black lab Jamie looks at me, expectant. I nod.

“You’re right, Jamie, it’s time,” and we head out for a walk. We live in a palm orchard. The pale roads are made of dirt and full of new divots from recent rain.

I know myself enough to know a little dose of awe is what I need to get out of the ghetto of my mind — to see something bigger than my own life. There’s a particular cactus I like to walk to. It’s an old cardon. It’s gangly. It’s so old that it barely has spines on it, and, here’s the thing: the ones it has are soft, not spiky. As we approach, a small bird flies overhead, landing on the cactus for a moment and then taking off.

I reach my hand out. I want to touch this old cactus. I pet the soft spines, feeling the tickle in my palm. I step in closer. I stretch my arms around the trunk. I feel the sensation on my inner arms, and I wonder about all it’s seen in its long life. It’s all such a surprise. I feel myself relaxing.

I laugh, thinking, the only cactus you can hug is an old one. I know I am like this, too. Softer. Less prickly with age. Today, turning my curiosity outward, I am filled with reverence. I rest my cheek lightly against the pale gray-green stalk. And I breathe.

I know now that the secret to aging well is feeling the wonder of the world and not just the weight of it. In this curiosity, you find expansion, you find creativity. Freedom — a shedding of things that no longer serve you. It’s how we keep that light in our eyes and make everyday of this marathon of life feel new.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Chip.

I really loved how Chip’s story started in the Redwood forests of Northern California. So I thought it might be fun to start our short closing meditation there too.

There is a fairly famous history of people meditating alongside trees, and so while we can’t be there ourselves right now, we can imagine ourselves there. Imagine ourselves sitting or standing comfortable at the base of one of those giant trees.

Breathing.

Feeling the breath.

Feeling the earth beneath our feet, our bodies.

And seeing ourselves, visualizing ourselves, however works for you, alongside these epically tall trees.

These redwoods on an entirely different scale to our own.

Yes, there’s a humility here: we can let go of having to be the center of the universe all the time.

There are other shows in town. We can let go of our weights, or at least hold them more lightly.

More importantly, in the shade of and connected to this miracle of trees, there is wonder here.

With our shoulders and face relaxed, we’re curious about what wisdom, what secrets this giant redwood might have to share.

Chip’s story is for me, one of alchemy.

Transforming his experience, at first dominated by his feeling the weights of his world, into one where he is in touch with the wonderful — the miracles of humanity. And of course that transformation is catalyzed by curiosity, by interest, by looking out.

So, let’s play with that alchemy ourselves too. And first we set up our channel.

However our body is, again, let’s feel how we connect with the earth.

Aware of the sensations of touch.

Aware of the gravity of our body on the earth.

And drawing the awareness up through our spine, and out through our wider senses.

The groundedness of our bodies connected with our wider minds, our imagination, our sense of space.

If you like in another language, our connection with the earth united with our connection with the heavens through us.

As Chip did, we all feel weights dragging us down, and all in our own way.

Maybe it’s work or family commitments.

Maybe it’s feeling we don’t have enough time to ourselves.

Maybe it’s fear about political or planetary crisis.

While the kind of weights can be common, we feel them in different ways.

Chip’s insight that he shares is such an important one.

That when we are in touch with wonder, it moves our baseline.

Our responsibilities, our challenges, don’t necessarily go away, but we can learn to hold them more lightly, so they have less power over us.

You can think of it as a simple formula, the more time we spend reflecting on what is wonderful, the more our minds are full of wonder.

But don’t take my word for it, instead consider it a hypothesis for you to test for yourself.

It’s part of the same mechanic of how gratitude journaling works: writing one thing at the end of each day that you are thankful for. Doing this over and over again orients our mind towards wonder.

For me, my go-to things to pop me into wonder are the night sky. It’s the detail in nature, it’s the detail in the patterns of my own hand. It’s watching someone do something selfless for another. It’s the way our body knows what to do, how to pump blood, how to digest food, safe from the influence of our chaotic selves. It’s my four year old daughter saying with absolute certainty that we are made from stars.

And if you’re looking for a simple practice to catalyze some everyday wonder for you, how about we go back to Nonni and make the shared intention to eat something new in the next couple of days: a fruit, a vegetable, a dish that we’ve never tried before, that we maybe don’t even know how to spell. Bringing full attention to that experience — curious about the dance that happens as our expectation meets the reality of taste, texture, smell and reaction.

So thank you again, Chip.

And thank you.

We’d love to hear your personal reflections from Chip’s episode. How did you relate to his story? You can find us on all your social media platforms through our handle @MeditativeStory. Or you can email us at: [email protected].