What we discover when we’re not looking

Sitting around tables with arms experts, moving missiles around a map of Europe as if it were a gameboard, On Being’s Krista Tippett grabs the moment to dislodge herself from the exhilaration of power. The journey that ensues leads her to a remote cottage in Spain where a chance encounter with a retired accountant, Robert, creates the space to redirect her life forever. Photo credit: Evan Frost.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

What we discover when we’re not looking

KRISTA TIPPETT: Looking back, if I could change something, I wish I’d been kinder to myself all along. A year or so ago, I was telling someone this story of my 20s and they said: “How did you get to be so brave?”

And I realized I’d never given myself any credit for being brave. I was always second guessing myself or planning what I had to do next. I didn’t give myself credit for how far I’d come and all the experiences I’d had. And I think it was brave. And I need to honor the bravery in myself so I can honor it in others.

This bravery is not about being fearless, because I wasn’t fearless. But in walking with the fear – and through it when everything I thought I knew turned out to be flimsy and questionable. And as I walked through it all, there was revelation, and there was confusion, and there was discovery.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Where for you, is the most beautiful place in the world? For Krista Tippett it’s a Spanish Island village in the Mediterranean Sea.

Krista Tippett is a journalist, former diplomat, and the long-time host of “On Being”. Today, she shares a story of when she took a break from the intensity of her life and just stopped to check in with herself.

In this series, we blend immersive, first-person stories with brief mindfulness prompts from me. I’m Rohan, your guide on this episode of Meditative Story.

Let’s take a moment to check in, to listen to ourselves. Just letting your inner life be what it is in this moment, and knowing it just as it is.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

TIPPETT: I spent most of my 20s in divided cold war in Berlin. It was the 1980’s. I was a thoroughly political person. I went there as a New York Times stringer, but for my last year and a half I was chief aide in West Berlin to the US ambassador to West Germany; a nuclear arms expert, a Reagan appointee.

I’m sitting around tables with people who move thousands of missiles around on a map of Europe as though it were a gameboard. Arms experts and foreign policy specialists, and people who have the ears of world leaders and who are defining policy around these weapons of mass destruction. I’m very close to genuine power and I’m aware of it in this room. It’s kind of incomprehensible. There’s an exhilaration to it, and there’s a seductiveness to it – and there’s an emptiness to it at the same time. It’s very exciting when I first walk into the room with these people, but then the longer I stay, at some level, I am profoundly bored by all of this. I don’t think this is how I should feel.

On the other side of the wall, in East Berlin, I travel to visit beloved friends in their apartment on the Chausseestrasse, a legendary street in Berlin’s history. They live in this apartment building where a famous dissident had lived. It has the history of East Germany in it and then it also wears a history of vanished Germanies. It feels ancient and a bit tumbledown in this chapter, forty years into communism.

My friends are artists. And the apartment is crowded and overflowing with half-finished paintings and musical instruments, and the world of their daughters – and just full of life and chaos. It’s warm and alive and everything in here matters. Everything we talk about really matters: friendships and words, food and pleasure, and whatever joy you can extract together. In the living room there’s a life sized bust of a mutual friend of ours, a poet who became so uncomfortable to the government that they banished him across the Wall.

He’s twenty minutes away from us, but they believe, and I believe, that none of us will ever see him again. So there’s grief in this apartment too, and longing, and love. It makes me realize that I’ve come to the end of what I can get out of my work in West Berlin. I long to get away and think all of this through: politics and its extremes and its limits. I don’t actually have space in my life for this, literally or even contemplatively. On the one hand, my life here is full of ideas, but on the other hand it isn’t full of a depth of thoughtfulness. I know I’ve had an incredible experience here, but it’s time for me to move on.

GUNATILLAKE: Do you ever feel like you don’t have space? Perhaps you’re in a phase of your life where that’s true right now. If it helps, take a moment to feel your feet on the ground, open out your chest. Relief is available in every moment when we remember to turn to it.

TIPPETT: It’s the summer of 1988, the year before the Wall comes down. No one can fathom that. And as desperate as I am to step away to make sense, I think I have to do something that sounds impressive. I give myself a four to five month stretch before I plan to head back to D.C. and more politics in the US. And I set off to write a novel.

I decide to go to the most beautiful place I’ve ever been in the world, this little village on Majorca called Deia. It’s not overrun by tourists. It’s a really eccentric, hard to get to, artists colony with a lot of expatriates. I found it through a journalist friend and fell in love with it.

It’s so lush, and fragrant. There’s so much color, so many flowers. You’re crunching almonds under your feet as you walk around. The beach is a mile’s hike, no road goes there, and it’s amazing. In my memory the journalist’s house is kind of like a castle and I have this romantic vision of going there to settle into myself and be creative and reflect. “I’m going to write my novel here.”

But then shortly before I’m to arrive, the charismatic journalist dies suddenly, of a heart attack. His widow offers to find me another place to live, and she does – but my idyllic vision is shattered. I had the perfect plan and now it’s coming apart. It all feels doomed and I feel very alone and adrift. But she connects me with this man named Robert who has a room in his house for rent. He’s an English accountant who retired to Deia to tend his garden and restore rare books.

I arrive and take a taxi to Robert’s house. It all feels very disorienting. I have the directions for where I’m supposed to go but it’s just a spot on the road. There’s no driveway or mailbox. The car stops and Robert is there to meet me. He appears to me this first time, I meet him as a grizzled man. He looks bedraggled and a little bit unsafe. I think he’s missing a tooth or two and he has berry juice stains on his chin and his clothes. And there’s not exactly a path to his house; we kind of fight our way down a hill beneath the road through the brush. And I think, “Who is this person? Where am I? What have I done?”

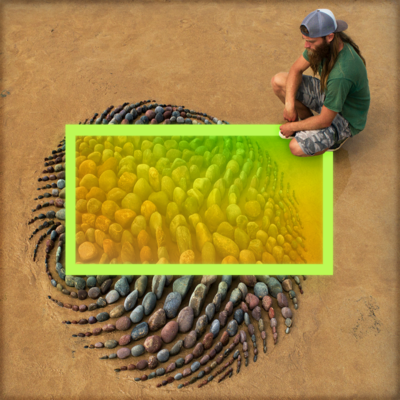

We finally reach the house and it’s so simple, but really so smart and sturdy. Nothing fancy but elegant. Amazing really. There’s a nobility to it, and a peacefulness to it. It’s just falling off the side of a mountain. I don’t actually know how it stays attached to the Earth. The house is just an add-on to the garden, which is wild and magical.

Robert sleeps in a hammock on the porch outside his bedroom every night. And I stay in a very simple room at the other end of the house. Everything is stone. Nothing fancy, but it’s perfect. I love it. I have a nice bed, and a little desk, and a tiny window. My view of the mountains is like a postcard and it is exquisite. The minute I walk in, the very first time, I think to myself, “I’m going to be really happy in this room.” And I am.

GUNATILLAKE: Can you catch the fragrance of the flowers in the garden? The mountains and their majesty keeping everything in perspective. Take it in for a moment. Let go.

TIPPETT: In Deia, I realize how exhausted I’ve become and how I hadn’t been letting myself feel that. This stranger, Robert, in his mid 70s, kind of nurses me back to health. I didn’t know I needed somebody to do that for me. He bakes bread from scratch every day and he makes everything out of his garden, these incredible salads where every ingredient is plucked straight from the ground. And there’s always a little dirt left in. He recommends books I’ve never read and gives me a cassette tape of Beethoven’s late quartets. It becomes the soundtrack of my summer.

I write all day, every day, on a schedule, but at lunchtime and in the evening I sit looking at the mountain and listening to this music. I get quiet for the first time in about 10 years. I start to pray, without calling it that at first. It takes me a while to figure it out, but eventually I realize that sitting in this garden is actually the whole point of being here.

This place isn’t on any of the maps that I’d been dealing with in Berlin. But it’s real, and it’s solid, and it matters. People are creating lives here that are as significant as those sitting around a conference table. And it’s a relief, because I think part of the reason I wasn’t able to imagine life beyond that career is that it felt like, if I could do that, which was so important, then how could I walk away from it? Sitting here, I remember that the world is complex and strange and that there’s importance all over the place, different forms of importance.

Coming out of that, getting quiet, I begin to open up to my inner life again. I ask the questions I need to ask about that world of high policy and why it’s wrong for me. It scares me to imagine the future differently, but I like myself so much more and I like myself in my body so much better sitting in this garden. It’s not about power in that sense. Being here leads me onto this whole other way forward. It leads me to what I do now.

When I was in Berlin, it was all very exciting. Diplomatic dinner parties. Adventures half-way across the world. But also long, long days of work. It was very intense. My work absolutely bled into my life. There was no separation and absolutely no value placed on the rest of my life – or in ever getting away.

What’s so striking to me now when I look back is how completely lacking in self awareness I was. How, in that life I was leading, it would have felt nonsensical to question it. Wearing myself into exhaustion was inevitable. I was so focused on accomplishment.

Now I’m amidst the incredible beauty of the natural world in Deia, with this completely unexpected person in my life, and his generosity and kindness. The power of that. It’s an experience of hospitality. A human presence that has no interest in, ambition for, or goals of impressing. It creates this space for me that I hadn’t been in, that maybe I’d never let myself be in.

This is my turning point. I don’t think I would have walked the direction I walked later if it weren’t for the time I spent in Robert’s garden. I wasn’t expecting it and I wasn’t looking for it.

GUNATILLAKE: What would it take for you to do something unexpected? How do we find the courage to do the things we really need to do? It’s always worth being in silence, asking yourself that question and listening closely to the result. Maybe you can do that later today?

TIPPETT: And there was something in that experience that flowed into everything I’ve done since. I wanted to make that possibility of reflection and restoration and life-giving questioning both more a part of my life but also more visible to others, more accessible. I think I had been asking this question all along: What do I want to do with my life? What kind of power do I care about exercising? What do I want to manifest in the world?

Looking back, if I could change something, I wish I’d been kinder to myself all along. A year or so ago, I was telling someone this story of my 20s and they said: “How did you get to be so brave?” And I realized I’d never given myself any credit for being brave. I was always second guessing myself or planning what I had to do next. I didn’t give myself credit for how far I’d come and all the experiences I’d had. And I think it was brave. And I need to honor the bravery in myself so I can honor it in others.

This bravery is not about being fearless, because I wasn’t fearless. But in walking with the fear – and through it, when everything I thought I knew turned out to be flimsy and questionable. And as I walked through it all, there was revelation, and there was confusion, and there was discovery.

Now I see that I was on an adventure, all along. I think the thing that I did right was that I kept directing that adventure in generative ways. I wish I had been able to be a little bit more pleased and relax a little bit more into it and just enjoy it when it was fun, to take even more pleasure in the good days and the excitement of the questions and the excitement of discovery. I had stumbled on this strange mystery and reality that the only real power that sustains us we find inside ourselves – and in the care and company of others.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: What inspires me about Krista’s story is her ability to simply stop, which of course is not simple at all. Coming from the intensity of her time in Berlin to the quiet of Robert’s Mallorcan garden, she still held onto the idea of writing her novel. But that plan soon vanishes and Krista truly stops trying to achieve, lets go, and opens up.

The same can happen in meditation. Even though it’s most associated with relaxation and letting go, many people still bring the mindset of achievement and goals to their practice. And while that can take you some way, there comes a point when you have to let go of all that.

There even comes a time when you have to let go of the idea of a meditation technique. And that’s what we’re going to do today.

No technique. Just meditation. No technique. Just mindful awareness. That’s what this meditation is all about. Pure, simple meditation practice.

And just taking a short while to settle yourself in for it. Closing the eyes if it’s safe to do so. Relaxing the eyes if you’d rather have them open. Letting your back be upright. Your head sitting elegantly upon your neck. Letting the belly be relaxed. The belly, soft and fluid.

Committing yourself to this short period of meditation. Enjoying the luxury of time dedicated to mindfulness. And in this meditation we’ll drop technique, drop the need to do anything in particular, and just be here. Be where you are. Aware, alert, and alive.

Nothing to do but be here and to be aware. Just here. Knowing what is happening while it is happening. Dropping all ideas of what meditation should be like, and just being present. And knowing what that’s like.

Not making anything more important than anything else. Just here. And letting mindfulness just do its job. Letting everything be known.

If you feel your mind has wandered away, remember that because we’re not looking at anything in particular, there’s nothing for it to wander away from. Just wakefulness. And what is known by that wakefulness.

If you feel your mind has wandered away again, and then you remember you’re meditating, noticing that in that very moment there is mindfulness. Mindfulness re-establishing itself. Without you having to do anything. All you have to do is be here.

Doing nothing. Alert and aware. Everything known. Nothing left out. Knowing what is happening as it happens, without judgment. And if judgment arises, allowing that, knowing that.

However your body is. Simple. Relaxed. Open. Aware.

Just here. Not doing anything.

Just here. Not chasing after experience.

Just here. Leaving everything alone.

And if thoughts arise, no need to go out to them and get caught up. No need to give them any more fuel. Just resting. And letting everything happen. Just being aware, just watching, whatever there is to be watched.

Enjoying the stillness of just being here. Enjoying whatever silence there might be. And when there’s noise, knowing that too and letting it be here.

Celebrating the fact that you have awareness at all. And letting it be free.

Just here. Upright. Relaxed. And alert. Dropping all techniques. Dropping all notions of what meditation should or shouldn’t be like. And just resting in awareness.

Not doing anything. Enjoying non-doing. Simple. Here. And now.

And if mindfulness slips away, noticing that the very moment you notice that, mindfulness is right there. Arising by itself. A natural quality of your mind.

Just here. Allowing all experience. Nothing special. Everything special. Everything special in Robert’s garden.