What my father gave me

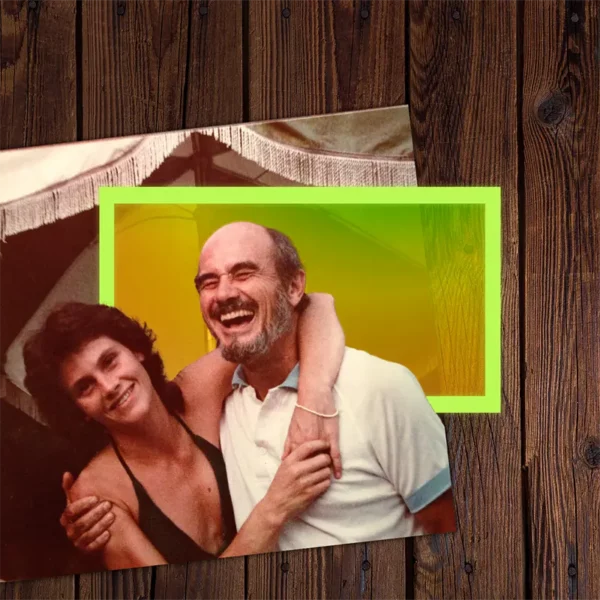

Shawn Colvin grows up in a dangerous house. There’s a dad with a hair-trigger temper. But there’s also a dad who builds things, and who plays music, who teaches Shawn how to play a guitar. Years later, an out-of-the-blue phone call gives Shawn the opportunity to explain to her dad what her childhood was like – and to forgive him. In this act of compassion, Shawn is able to let go of her own burden and find compassion for herself — who she is now and the lost little kid she used to be. Photo credit: Joseph Llanes, David Sokol.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

What my father gave me

SHAWN COLVIN: Church is a happy place, a place of fellowship, music, and… safety. I feel a sense of comfort in church. Not a comfort of faith, a comfort in community. My mother is a staunch church goer, but we never talk about religion. It’s social. It’s musical. My world expands in the church. When I touch the collection plate I feel part of something bigger than me and my family, part of a ceremony.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Shawn Colvin is a multi-award-winning singer-songwriter and musician and last year saw the 30th anniversary of her studio debut Steady On, which received the Grammy for Best Contemporary Folk Album. In today’s Meditative Story, Shawn shares a candid and challenging story from her childhood about the liberating power of forgiveness, both for the person being forgiven, and the one doing the forgiving.

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat and Thrive Global, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

COLVIN: We don’t speak often, so I’m surprised by the call. It’s early evening, dusk. I’m in the dining room, at the table. I live on the border of Venice and Santa Monica, in L.A., in a cozy, Spanish stucco house I rent with my husband. It’s 1993. I’ve just released my second album.

The walls are white. Arched doorways lead to the kitchen and to the living room. It’s very spare except for the hutch, the table, the chairs and the bench, all made for me by my father.

He is trying to be lighthearted but I can hear the tension in his voice. He makes a few jokes and then quickly arrives at the reason for his call. He asks, “What was your childhood like?”

I don’t quite believe it. It’s the question I’ve probably wanted my father to ask me for my entire adult life. And one I desperately want to answer.

I pause. I’m wary. Both because I don’t fully trust him to hear my answer, and because I’m not at all prepared. I don’t actually know what I want to say. What if once I start speaking, I chicken out?

“If you really want to know, call me back tomorrow at 8:00 AM.”

I’m not a perfect, happy-go-lucky, easy to please, easily amused child. I’m a challenge. I’m anxious, phobic, prone to depression. Nobody quite seems to know what to do with me. I bring my parents to the end of their rope.

It’s 1960, in Vermillion, South Dakota. My parents are so young, in their early 20’s. My father has a hair-trigger temper. He administers regular spankings. But it’s more than that: Once, when I deny stealing my brother’s peppermint candy, my father chases me, and pins me down to smell my breath. Another night I dislike my dinner and refuse to eat – he kicks my chair over and drags me into the living room to admonish me. This kind of thing goes on for years. The house feels dangerous.

Neither of my parents are prepared for this, for children, or marriage. Even at this age I have the sense that my father would rather be elsewhere. He runs my grandfather’s newspaper business. When he isn’t at work, he retreats to the garage. He makes things: the furniture in our family room, the table and chairs, a hutch. He refurbishes a Volkswagen Karmann Ghia. He builds a canoe. He kits out his beloved Peugeot bicycle.

When he buys me an Atala racing bike I take it apart and put it back together. I pack the hubs, retape the handlebars, change the cable housing. I spend all summer in the garage with my father, doing what he loves. And I love it too. It is a bond of sorts.

There are four of us: my mother, my father, my big brother, and me. We each have our own rooms. I’m expected to stay in mine at night. My bedroom is a baby pink color, perfect for a little girl, with stuffed animals and Barbie dolls. I was supposed to love it.

My nightly visits to my parents room frustrate them but they try to console me. When alone in my room at night, I‘m gripped by fear – fear of dying, fear of intruders, fear of thunderstorms. I try to rein it in, but the dark nights alone in my room with the door shut are more than I can bear. Climbing into bed with them is not an option – that isn’t done in our house. I’m both scared to stay in my room, and I am scared to leave it.

My fear finally pushes me to test the waters again, to look for comfort. One night my father’s had enough. It’s past midnight. I’ve worn out his patience. He takes me to the living room, sits me in a chair, pulls another chair up close to my face, and he says, “You’re going to stay up all night to see what it feels like.” He keeps a close watch. When I begin to nod off, my chin falling slowly to my chest, he shakes my shoulder. Eventually dawn breaks. I am free.

My anxiety doesn’t vanish. I learn to cope with it without asking for help. I internalize the idea that I am damaged, beyond repair. That I was born this way.

It’s clear I can’t get my father’s help. So instead I seek his approval. And I do so by becoming like him.

GUNATILLAKE: Ok, the start of Shawn’s story has been a lot. I’m grateful for her telling, but it is a lot. Notice how you feel. Any patterns of tension in your own body, any holding. Allow it.

COLVIN: It’s my father who makes music an essential part of my life. He plays guitar and banjo, he loves to sing. He has a big folk music record collection – Pete Seeger, the Kingston Trio. I study those records, pour over the photographs, memorize the liner notes, the songs, where they came from, who sings them. I listen and listen and listen. Now and again my father gets together with two of his buddies and they pretend they’re the Trio, wearing striped shirts, singing and playing their hearts out.

I take piano lessons from the age of six. I enjoy it because I love music, but I’m not passionate about it. But things change when I turn ten years old. My father tries to get my brother and mother to play the guitar. My brother’s not interested – he wants to play violin. My mother wants to learn to strum Edelweiss, but she doesn’t stick with it. So one day I meekly raise my hand and say, “Well, uh, I’m interested.” My dad is delighted. He finally has a protege and another bond is forged between us.

I learn on a tenor guitar. It has four strings, better for small hands than your traditional six. It’s not easy to play a steel string guitar. It hurts. But the pain doesn’t bother me. My father teaches me “This Land is Your Land,” “Shenandoah.” One of my father’s friends teaches me to finger pick, which is incredibly difficult. I have to dissect it, move for move and note for note. Slowly, painfully.

I fall in love with that guitar. I still have it. I cloister myself away in my room with it. I revel in the shining sound it makes. I sing with it. I claim it. It becomes my instrument.

While the guitar is the music of home, the organ is the music of church. To me, the guitar is private, the organ is a tool that binds the community together. The church is always filled with light, which pours in from outside through the large windows. The high ceilings soar above us. The whole sanctuary feels enormous to me, majestic. I love the gorgeous wooden pews and the rich, burgundy red carpeting, the chandeliers. The organ sits above and behind the pulpit, yet its music is everywhere around us. I’m transported by the mystical sound of it.

Church is a happy place, a place of fellowship, music, and… safety. I feel a sense of comfort in church. Not a comfort of faith, a comfort in community. My mother is a staunch church goer, but we never talk about religion. It’s social. It’s musical. My world expands in the church. When I touch the collection plate I feel part of something bigger than me and my family, part of a ceremony.

Our songs of faith are full of love and joy and celebration. There’s no big emphasis on sinning or anything like that, just a kind of exultation. No one’s unkind on Sunday. My father is on his best behavior – everyone is watching. He even seems to relax.

My father doesn’t care for the solemnity of church but he adores singing. When the hymn lends itself to ridicule he leaps at the chance for a joke: “Let us break bread together on our knees,” he sings, and pretends to snap a long loaf of bread across his knee. He makes “Oh lord, my god” into a plea for deliverance from the sermon.

It’s no wonder when I take my place in the junior choir balcony I pass notes to my friend Ruth during service. Her father sits below us at the organ and glares in our direction as we try to stifle our giggles.

Sundays are good. There is church, there is Sunday dinner, there is the Wide World of Disney. The single drawback is that the next day is Monday, and I have to go to school again.

Music is everything to me and Ruth. Ruth is one of 5 children, together they make up the Noble clan. Her older three siblings – Jane, Kris, and Dave – are the keepers of the Beatles records. We lurk around her house for hours on end, waiting for one of them to drop the vinyl on the stereo and put the needle down.

The Nobles live on North Yale Street. My goodness, the hours I spend here. There are so many nooks and crannies to hide in. It’s a rambling Victorian house with gables and an attic, three floors, and a front porch that wraps around. There are rooms everywhere.

Under the staircase is a crawl space with a door, a special little hiding spot for secrets and ghost stories we tell to scare Ruth’s younger brother, Paul. There’s a sitting room, and a living room, I don’t know which room is which.

The Noble house is crowded, pulsing with the energy of five kids. Always somebody running up and down the stairs. Her mother serves three meals a day and it feels like I am here for most of them.

We wait like little puppies until Kris or Jane or Dave is in the mood to put on the Beatles. We sing along and wait to be called to dinner by Phyllis, Ruth’s mother. We beg our parents to allow me to spend the night. This house is full of life, and love, and music, and dreams, and possibility. To me the Nobles are what a family should be. Here I feel understood and accepted. Like I belong.

On summer nights, around dusk, we drive out to the USD letters with Ruth’s brothers and sister. They must be like the Hollywood sign, these gigantic white letters on the hillside, heralding the University of South Dakota. We go down the bluff and follow the road that runs along the Missouri River to catch a glimpse of the letters. They’re a destination. The wind blows through the backseat windows, and I breathe in the warm, alfalfa-scented summer air as I look up at the first stars in the night sky, savoring my chocolate ice cream cone. We drive there, we turn around, and we drive back. They’re always a revelation to us, the letters. Like, there they are, every single time.

I don’t think Ruth or her parents know how much I suffer at home. How out of place I feel emotionally and mentally, and how tortured I am in ways I can’t even describe, and which they couldn’t possibly understand. I keep it a secret. My life at home feels private, and embarrassing. But there is something here I don’t get at home, and I bask in it. Moments of peace, and perfect contentment.

The last time my father raises a hand to me, I’m 15 years old. He’s ashamed. I enjoy that he is embarrassed. I don’t say a word. I don’t forgive him. It’s the last time it ever happens.

It’s 8 am, which, as a musician, is early for me. I sit at the dining room table my father built, waiting for his call. I’m in my periwinkle blue robe with flowers on it. Will he do it? I’m scared. Almost as scared as I was in my room as a child. I don’t want to hurt his feelings. But I need to tell the truth.

The phone rings. We have a warm initial exchange. My heart is racing. And then he asks me again. “What was your childhood like?”

At first it’s hard to get the words out. But I say it. “Well, you were violent with me many times. That’s the main thing I need to tell you.”

And he says, “I know it. And I’m sorry.”

I’m shocked. The possibility of my father understanding my pain has been too dangerous to hope for. Because I know I couldn’t have handled him being defensive. So for my own protection, I don’t let myself think that much about it.

I’ve assumed our past would be all mine to carry and make sense of, and to forgive as I could.

And now it’s over. Just like that. And I forgive him. I just let go of all of it. It is such a relief.

I don’t say, “Remember this time, remember that.” I don’t rake him over the coals. I don’t feel like anything more has to be said, and he doesn’t offer up a reason. And it changes everything, like a weight has been lifted. I think we all have our childhood wounds, some more than others, but I think all we ever really want to hear is not, “I did the best I could.” But just, “It’s on me. It’s on me, and I’m sorry.”

GUNATILLAKE: Again, notice the reactions that are here. Reactions in the mind. Reactions in the body. Just notice. No need to push away or try to make it all lovely. Because sometimes it’s just not.

COLVIN: People sometimes ask who benefits more, the forgiver or the forgiven. I think it’s maybe the person making amends, asking for forgiveness, who gets more out of an apology. Putting yourself out like that also means accepting whatever you get back. Which may not be what you hope for. You may not actually be forgiven. The power of making amends lies in the humility of it, in listening to and really hearing the truth, and in the willingness to clean up your own side of the street. To say you’re sorry – and to mean it – is an immensely powerful thing.

I forgive my dad. He was flawed, deeply, but he was always lovable. And he’s forgivable.

Up until now I’ve spent my life in terrible conflict over which to put my faith in, Jekyll or Hyde. But I don’t have to look at him that way anymore. Like me, like all of us, he is both.

Where there is pain, there is also joy. They will always coexist. I consider myself very fortunate. Growing up in the town of Vermillion, I got everything I needed to survive, however alone I felt in my family. And not everybody gets that. I was given the tools in those first 10 years to build the best parts of my life: music, friendship, passion.

I was the musician, I was the artist, I had a wild streak. I wasn’t tameable. Nobody knew anything about depression, or anxiety, or how to nurture an artistic temperament. My father took many things from me: my confidence, my sense of safety, my ability to trust. But he gave me music. He gave me drive. He fueled my passion. He showed me how to dream. And he gave me so much laughter.

After his call, for the first time, I look at my father not just as my father, but as a man. It’s like a wall breaks. I see someone who is kind.

An extraordinary thing happens: I feel lighter. It takes so much energy to hate. To hold on to resentment. It is a terrible feeling, I loathe carrying it. But as soon as I forgive him, the resentment is lifted. Because in forgiving him, in having compassion for him, I am able to feel those things for me, too.

When I think about it now, I suspect that my father probably did understand me. Because I see so clearly that my father was a hellion, too. And he couldn’t control me. Because I think what triggered him most was the recognition in me of aspects of himself. The fear. The darkness. The longing for music and love and adventure. And escape.

Whatever his failures, I know now: He got me. He did. And I forgive him. I have compassion for him. As I have compassion for that little girl in Vermillion.

I have my own daughter now. I do the best I can. And I know how to say I’m sorry. I know how to treat her with compassion. My father taught me that.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: That was intense. We all have different relationships with our fathers. And for many of us they are difficult. So whether that story has brought up stuff for you or not, I wanted to share a meditation about dealing with difficult emotions. If you need it now then good. If you don’t then that’s good too so you can practice it for when you do.

And what we’ll do is go through a simple four-stage mindfulness process. And the first stage is recognizing, recognizing what is happening in your mind right now. Giving it a name: Sadness.

Distress. Fear. Anger. Calm. Whatever you recognize to be happening right now, in this moment, giving it a name.

This is anger.

This is stress.

This is what is happening and I recognize it.

Now take a moment to recognize if there are any physical sensations that go alongside this emotion. Most likely there will be some kind of unpleasant sensation in the body. Perhaps tightness in the chest or an elevated heart rate. Perhaps an area of tension or heat. Just recognizing what is present in the body, giving it a name.

This is tightness.

This is heat.

Whatever you recognize to be present, giving it a name.

After recognizing, the next stage is allowing. When having a difficult experience it is very common to want to push it away.

I don’t want this.

Or we can also use the difficult as an opportunity to criticize ourselves. Thoughts such as:

I shouldn’t be feeling like this.

I should be stronger than this.

I’m useless.

But by adding this second layer of negativity to an already difficult experience, we are just adding more fuel to the fire. So whatever is happening right now is happening. If that’s calm, then there is calm. If that’s fear or sadness, there is fear or sadness. Allowing ourselves to just feel those emotions and the physical sensations that come with them, as they are. Not adding any more layers of judgment or story, just experiencing what is here right now on its own terms. Allowing what is here to be here. Even if it is difficult, bringing interest in. Letting your interest and curiosity help steady you in what is happening. Allowing.

And if it really is too difficult to allow what is happening, then allow that difficulty. There are times when things are just too intense and that’s ok.

After recognizing and allowing comes investigation. Letting the kindness of your attention investigate what is happening. What is calling for attention right now? How does the body feel right now? If there are areas of heat or tension or movement, is the heat or tension uniform throughout? Where are their boundaries? Do the physical sensations change over time? Investigating how you are seeing things right now?

After recognizing, allowing, and investigating, the fourth stage of this mindfulness process is called non-identifying. The simple idea that if you can observe all this, then maybe it’s not part of you. Maybe we don’t have to wrap up our identities with all these stories and judgements. Non-identifying and relaxing the mind.

This meditation has gone through a guided process which is especially useful when dealing with difficult emotions. Using the four stages of recognizing, allowing, investigating, and non-identifying. R-A-I-N or rain for shorthand.

I hope that’s been useful. It’s a process I use all the time when things get a bit much. Thank you for being with us.

Thank you and go well.