Redefine your generational patterns

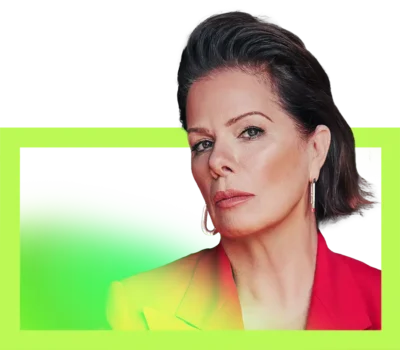

Tony and Academy Award-winning actress Marcia Gay Harden recognizes that for her, like so many of us, she is who she is because of how she was raised. In this episode, Marcia Gay tells the story of how she’s learned to reevaluate all that she inherited from her father, and to let go of the habits she learned from him that no longer serve her.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

Redefine your generational patterns

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: Marcia Gay Harden is a Tony and Oscar-winning actress. In today’s episode, she tells a story about recognizing that she, like so many of us, is who she is because of how she was raised. Marcia Gay is thoughtful in her reflections on everything she inherited from her father, and today she’ll share how she’s been able to let go of those habits she learned from him that no longer serve her.

From WaitWhat this is Meditative Story, where immersive first-person stories and mindfulness prompts inspire you to reflect on your inner life. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open, your mind open, meeting the world.

MARCIA GAY HARDEN: I sit reading my book relaxing on our living room floor. The walls are filled with woodblock prints of fisherman in straw hats and watercolor paintings of peacocks — my dad’s favorite bird. I breathe in the sweet, earthy aroma of chrysanthemums, lavender, and roses that sit at careful angles in vases around the room. Ikebana, the Japanese art of flower arranging, is a hobby my mother has taken up since we moved here to Japan. She insists on bringing beauty into our home, wherever we are.

We move every two to three years, depending on where my dad gets stationed. For the last two years we’ve lived in this house, perched on a small plateau dividing Area 1 and Area 2 of the Yokohama naval base in Japan. I’m 10 years old.

Just as I turn the page in my book, my sister Sheryl calls out “Dad’s home.” My posture stiffens. My dad’s been away at sea for the past six months on a naval ship. When he’s away, the atmosphere at home slowly but surely relaxes. But now he’s back.

Everybody jumps up to attention! My four siblings, my mom and me. I put my book away. I feel compelled to put anything of pleasure away. I fall in line to be helpful. To be on duty.

Dad’s a big man with an imposing presence. As he comes in through the front door, even before setting his briefcase down, he barks orders. “ As soon as you get those God Damned toys off the porch – I’ve got ciggie booze for you!” Ciggie booze are little treats. Candies or hair barrettes. Maybe a pearl necklace that he’s picked up from various ports in his travels. Why “ciggie booze?” Because that’s what the sailors always wanted brought back from the states, ciggies and booze. We, of course, answer “sir, yes sir! We pick up the toys, and get in line for our ciggie booze. My Dad has two sides. Commanding, yet also, kind, and playful. But he’s unpredictable, and I never know which side of him will enter the room.

The most important thing when dad’s home is to never be idle. I have to produce results.

As dinnertime approaches, everyone has a chore. One person sets the table, one person helps clean up, one person washes the dishes. It’s like a ship. If everyone’s doing their job, the ship will reach its destination safely. With our family of five kids, it can be like herding kittens, but if each of us is doing our jobs, the family will function like it’s supposed to. That’s what my dad’s learned in the navy, and what he passes on to us.

I don’t want to be fearful of my dad. But I am. He loves us deeply. He wants the best for us. But like I said, he’s unpredictable and I never know what mood he’ll be in when I come home from school. I’m always afraid of getting in trouble, but I’m not sure for what? He’s exacting, his standards are sooo high, and if I mess up I might be put in a corner. I don’t want to be shamed. Humiliated. Yelled at. No kid ever wants their parents to be mad at them. So my days are overshadowed by a constant sense of anticipating what could go wrong. If things are in order, I can feel safe.

My dad’s impatience becomes my impatience. These patterns I inherit silently shape my way of being in the world.

We live in Washington, D.C. now, where my dad works on the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

In the den my Dad sits in his brown leather armchair, surrounded by books and beautiful relics from my parents travels. A Tibetan dancer. A Japanese doll made of china, protected by a glass case. An aria from La Traviata blasts through my dad’s speakers and fills the room. He leans back in his armchair, holding a glass of brandy, eyes closed, immersed in the music.

I stand in the den door frame with my date, a boy from school who’s taking me to the movies. My dad has insisted he come inside. “He can’t just honk the horn, God damnit” he’d said.

My dad sees us standing here. My date looks nervous. “Sit down!” my dad barks. In my head, I’m like, “Daad. NOOO.” But, Here we go. The movie we’re supposed to see starts at a certain time! I’m impatient to get going. But my dad insists, “Now. Sit down. Listen to this.” I’m mortified. I try not to roll my eyes as I sink into the couch.

The music swells. Dad’s lost in the beauty of the sound. He starts to sing along. My dad’s not a singer. And it’s a woman’s aria. He doesn’t exactly match the pitch. But as Dad sings, tears fall down his cheeks. I’m half embarrassed, but in truth, kind of proud of him. He’s so engaged in the world of this song. I see how it connects with something in his soul. It brings out this whole other side of who he is. A side that has nothing to do with the regimented sense of self that he’s been taught to live with.

When the aria ends, my dad rises up in his chair, the brandy still in his hand. He looks directly at my date and barks at him, “That’s the best goddamn aria I’ve ever heard!”

“Best – goddamn – and – aria” are three words that I don’t think have ever gone together before.

As we hasten to the door, my dad calls out, “Love you Marcia Gay!”

I smile. Underneath my father’s gruff exterior, his impatience, his relentless desire for order is the soul of an artist.

GUNATILLAKE: There’s a lot happening here. Appreciation, absorption, power, fear even. What is it that stood out most to you? And does that response show up in a particular place in your body I wonder?

HARDEN: I smooth my hands over my long white apron, and look around at all the shelves of pottery that line the walls. Plastic sheets cover some of the pieces as they dry out. Others have been recently fired in the kiln and shine with black tenmoku glaze. Soft jazz music plays from a small speaker in a corner of the dark wood studio.

I sit in a semicircle with a group of students, each of us perched behind our own large pottery wheel. Our teacher walks among us, gesturing to the triangular slabs of unformed clay that we’re learning to shape. Within arm’s reach are my tools: a sponge, a wire clay cutter, and a rib—a thin crescent shaped piece of wood to shape the clay.

This is my first class at the Greenwich Pottery Studio. The space is tucked into a low-rise brick building in the West Village, in New York City.

I’ve inherited my parent’s deep love of the arts, but for me, it’s acting. It’s 1993, and I’m 34 years old. After years of waiting tables, and then a few years of doing film and TV roles, I’m now making my Broadway debut. Angels in America.

For a long time, since college, each of my days held a different agenda. Now that I’m in this play, suddenly I have a prescribed schedule. AND IT’S GLORIOUS! I know exactly what’s expected of me for the entire upcoming year. I know where I have to be for every matinee and evening performance. My obligations begin at “half hour before the show”. But now, I know my hours off. I feel compelled to use my free time to expand the things I can do in the world. Always be producing.

I slap the clay down onto the metal part of the wheel just like the instructor demonstrates.

I try to center my mound so I can start to shape it. I push my hands deep into the clay. The amount of force it requires is remarkable. A few moments in, my piece collapses. Am I forcing it too much? I try to use my own center to center the clay. I sigh. Deeply frustrated. Why am I not good at this?

The impatience that I saw in my dad in childhood is now something I see in myself all the time. I am literally one the most impatient people you’ll ever meet. It influences every part of my life.

Even just walking down the street behind a slow walker, I’m always thinking, Move. Just move. It’s NY for Pete’s sakes. In my career it also feels like everything takes so much time. Casting. Auditions. Callbacks. And then nothing, It all feels like a slow-turning wheel, and leaves me wondering, Why don’t people respond? Hurry UP!

As my pottery wheel continues to spin, I have to keep starting with fresh clay again, and again, and again. It’s a very dirty process. Clay flies all over the place. My hands are covered. My face is smeared.

I feel a great deal of self consciousness. My eyes surreptitiously dart around the room to see if anyone is getting this right. I see my classmates giggling at their own work. Turns out, none of us are that good at this. Suddenly the room bursts into a round of encouraging applause. My classmates are celebrating someone making their first properly-shaped bowl. I clap too. The group is here to support each other. It’s like a womb of connection and warmth.

Finally, the instructor comes over to me and hovers over my wheel. With his help, I begin to see my clay take shape. This feels great. But with all of his help, part of me still feels like I didn’t really do it.

The first time I’m able to craft something on my own, without the instructor’s help, it’s a wonderfully unique, slightly deformed creature that I just have to keep because I somehow love it more than anything else. But it takes time. Centering the clay takes time. Centering myself takes time. The whole thing takes so much time. It’s something I constantly wrestle with. It’s introducing a different way for me to be than the way I was raised.

My feet click evenly on the sidewalk as I approach the stoop of our Harlem brownstone. From the school across the street, I hear the excited shrieks of the kids playing out in the yard during their PE time. Our block in Harlem is so beautiful. It’s very, very family. I’m excited to return to my nest — with my three beautiful children and my husband.

But the transition back home is often hard for me. I’ve been away on a long film shoot, making a movie on location in Toronto. I have to reintroduce myself back into a life I haven’t been living. A life that my husband and the kids share. As I walk up the front steps, I clutch a little bag full of presents for the kids. Bath bombs, and maple syrup from Canada. My version of Ciggie Booze. And, I think of what it must have been like for my dad coming home to us after months away at sea.

I open our front door and the aroma of lavender hits my nose. It’s my mother’s influence — just like her, I always like to have fresh flower arrangements in the home. I make my way into the house. The fading sunlight from the bay window illuminates the gold and earth tones in the living room.

But immediately I see that nothing is in its place. There are toys scattered everywhere. My three young children are playing in the middle of it all, my husband sprawled out next to them. I feel my chest tighten.

Why is everything such a mess? Why didn’t they clean up before I got home? The chaos makes me feel unsafe I can feel my impatience starting to bubble into anger.

I feel l need to put everything away before I can hand out their presents. “Mom, you’re home!” my kids exclaim. I distractedly greet my family, but I can’t fully acknowledge them in the midst of rushing to refold the blanket on the couch and put the pillows back and get things in order. “We missed you!” my kids call out. “I missed you too,” I say, as I snatch their toys out of their hands as they’re still playing with them. It’s time to put them away.

“I’m still using that, Mom!” my oldest cries. It awakens me out of what I’m doing. I slowly put down the toy. My kids are trying to talk to me, but all I can think about is getting things in order.

Just like my Dad used to do.

I feel a pang of guilt. Why do I need to restore order before I can connect with my children? It’s as if I’m looking into a mirror and I stop and think: wait a minute, this is not my true reflection. This is a reflection of history. The history of how I was raised, and everything I learned from my father.

I sit down on the floor, in the midst of what feels like disorder. In what feels like someone else’s world—my kids’ world. It dawns on me that I need to make a change. Can I let go of the fact that this room is a little bit messy? To surrender the patterns and behaviors passed down to me — so deeply ingrained in the fabric of my being. Can I make myself a part of this space, rather than making my kids conform to MY space? How do I refocus?

It’s not that my whole way of being changes in this instant. It takes a lot of work. It takes years. The unpredictability of my life has me constantly trying to organize things so that I am in control of things. There are plenty of times when I don’t manage it well, when the impatience I’ve inherited still comes out as anger. But then there’s a day when I’m venting mad about being late getting the kids to school, and my child looks up at me and says, “Mom, I’m afraid of you.” This is startling. This is when I think, Marsh, This isn’t okay. Growing up, I was afraid of my dad. And yet in so many ways, I’m still him.

My dad gave me so many gifts. His love for me. His love for art. He and my mom gave me the gift of travel. They showed me the world. But I know I have to work to remove the fog that gets in the way. The impatience and bluster and anger at things not being ordered, and on schedule. And this work takes patience.

GUNATILLAKE: It’s heavy isn’t it? The replaying of patterns we’ve inherited from our parents. And it can bring up a lot so just take your time. Soften the shoulders, the belly. Giving space for whatever’s come up.

HARDEN: I sit at a long table in a white-walled pottery studio. Through the window, I can see out into the parking lot. You’d think a pottery studio in Faenza, Italy might overlook a field full of sunflowers. But this is a ceramics factory town. The studio is practical. Perfunctory. I scan the row of pottery wheels lined against one wall. There are shelves, sinks and a glazing booth in the middle of the room.

Sitting next to me are my three children. They’re not even children anymore — twins Hudson and Julitta are 19, and Eulala is 24. I’m thrilled that they want to hang out with their happily solo mom that they’ve agreed to join me for this week-long pottery workshop here in Italy.

We all work alongside each other, my children and me. There’s a calm to this process. There are certain things you can’t hurry, and I now deeply understand that pottery is one of them. You have to throw each piece, center it, let it rest, trim it, let it rest, fire it, glaze it, let it rest, and fire it again. One pot can take a week and a half to make. When you try to rush it, something usually cracks.

Raising kids is another thing I’ve learned you can’t hurry.

I observe that Eulala is like me with the clay. Aggressive. “Why isn’t it centering?” Eulala cries out, clay slipping through fingers. I know the feeling. And I know Eulala will flourish when we get to paint our pots. Next to Eulala, That’s Eulala’s true artistry. Next to Eulala, Hudson is focused. He’s doing good work, steady work.

Then I look over at Julitta. She’s the most patient of all of us. And she’s doing the most beautiful pottery of all of us. Our teacher Roberto comes over and exclaims, “She has it.” She seems to sense that she can allow herself to become one with the clay, to enter its world.

On our lunch break, We swim and eat. We play games. Bananagrams. This trip isn’t just about pottery. We’re here to be together without only one person being in charge all the time. Without me being in charge all the time.

In the morning the kids don’t always show up at 7:30 for the breakfast of croissants and berries. The breakfast that I’m paying for by the way. But I don’t say anything. I just pack the croissants in napkins and bring them along for them to enjoy whenever they want.

We allow ourselves to indulge in pleasure. Pleasure does not make the ship run. Restoring order makes the ship run. But pleasure makes my life run better. For now, I’ve shifted enough that I can relax into it.

My rigid upbringing taught me behaviors that left me feeling impatient, and angry, a lot of the time. All of that impatience was just me trying to anticipate what could go wrong, trying to make my world safe. But I don’t have to apply everything I learned from my father to my life. I don’t have to keep repeating those habits.

It’s like a hill. Where water goes down the hill in the way it always has. Carving a path for itself. You’ll repeat the same learned behaviors you were taught early in life unless you learn to recognize which ones aren’t serving you anymore. And then it’s time to make a change. You have to learn how to block the path down the hill, and restream the water another way. Because the habits we inherit from the people who raised us, they don’t have to define who we are.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: Thank you Marcia Gay.

Marcia Gay’s story has me reflecting on how much of mindfulness — certainly for me — is a path of unlearning. So that’s the theme we’ll take for our meditation together now.

Our minds as they are, are, as Marcia Gay says — to a large degree — the result of that which has come before. So let’s look at them as they are now.

Letting the body be comfortable, let’s just take 30 seconds or so to watch our mind, and notice what is happening, interested in what patterns or moods or vibes might be present.

Ok, what did you notice that you might want to unlearn.

Maybe you would like to bring some calm to a busy mind with some soft, conscious breathing?

Or perhaps what you noticed was your mind getting caught up in this and that and you’d like to be able to let things go a bit more? If that’s the case, you could note the words let go whenever you notice it happening.

Or maybe the pattern you’re keen to unlearn is something about negative self-talk. If that’s the case for you, why not use the phrase, ‘thoughts are not facts’ when self-judgment arises.

All different ways to unlearn our patterns.

So take one of these and give them a go for a little while, or you can do whatever you think is best to unlearn the pattern you want to unlearn.

This is the work, seeing patterns, patterns we might not have been aware of. And then, actively deciding to do something to work on them.

But, it can be too easy to focus on the negative.

So as Marcia Gay also pointed to, let’s finish off by reflecting on what are the positive qualities you have that perhaps you gained at an early age.

Mine is independence I think.

What is the quality or qualities that you have had from childhood that you want to celebrate?

Choose it, name it.

And most importantly, celebrate it.

Thank you again Marcia Gay.

And thank you

Go well.

We’d love to hear your personal reflections from Marcia Gay’s episode. How did you relate to her story? You can find us on all your social media platforms through our handle at meditativestory, or you can email us at: [email protected].