The call of the life that wasn’t

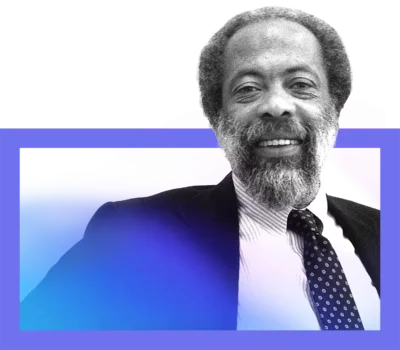

Russ Ellis has led the kind of life they write books about. The first full-time Black professor at California’s Claremont Colleges. Acclaimed sociologist. Celebrated sculptor and painter. Even a recording artist. But as he reveals in this episode, even the fullest life can be haunted by a single event half a century earlier.

Table of Contents:

Transcript:

The call of the life that wasn’t

RUSS ELLIS: June 30, 1956 is a bright and smoky day in Los Angeles, or so I’ll piece together later. From the moment I wake up, I am so focused I can only dimly register my surroundings. I have one job: Get to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

For years, my life has been a vector, pointed directly at an event born 2,700 years earlier. For an athlete like myself, there is no greater achievement than the Olympics, no higher honor, no clearer test of one’s worth.

How do you get into the Olympics? You show up at the Coliseum, this glorious white art moderne monument to competition, and you run faster than the other guys. Not all of them. Eight of us have made it to the 400-meter dash trials, and to advance to the Olympics, I just need to be in the top four.

ROHAN GUNATILLAKE: At 86, Russ Ellis has led such a rich life: a celebrated sociologist at UC Berkeley and then a vice chancellor there, the first full-time African-American instructor at The Claremont Colleges, a father, a grandfather, an accomplished painter and sculptor. And just last year he cut his first album. But for all that, a single minute some 65 years ago has haunted him to this day.

In this episode of Meditative Story, Russ reflects on what might have been, that variety of thought that infects all of us at some point. How would my life have been different had this one moment gone another way? What are we to do with those nagging questions?

In this series, we combine immersive first-person stories and breathtaking music with the science-backed benefits of mindfulness practice. From WaitWhat, this is Meditative Story. I’m Rohan, and I’ll be your guide.

The body relaxed. The body breathing. Your senses open. Your mind open. Meeting the world.

ELLIS: Elsewhere Germany is losing Stalingrad, and Japan rolling through Burma, but my world is wind. It rips through the San Gorgonio Pass, howling over low scrub, whining across sun-baked boulders, rattling the windows of the tiny, hot, lonesome room that will be mine for six unlikely years.

It’s the early 1940s. I am a city boy exiled from the city, my world turned upside down precisely as the world itself has turned upside down. One day my mother took one last look at her life in Los Angeles, threw some clothes in a suitcase, and ran off to New York. It’s just me and my father at that point, but then he’s drafted, and it’s just me.

At six, I am sent to a small farm in San Bernardino County, outside the parched, burgeoning steel town of Fontana. The Black folks live in a little enclave called Landon – a rural ghetto, essentially – surrounded by orchards and vineyards and fields of those boulders. The farmer who lives here has built this house by hand, and now in their rough way he and his wife have taken me in, giving me a room of my own in the shadow of Mount Baldy.

Farm life is an adjustment. We raise what we eat – corn, pigs, cows. Mistakes earn a whipping. Our heat comes from a wood stove, and going to the bathroom means walking to the outhouse. Once, in the middle of a dark, frigid night, walking down the dirt driveway, I have the singular human experience of stepping barefoot on a snake. Days are quiet. The Klan is active in the surrounding community, but my existence is insular, given to fantasy. Mount Baldy looms to the northwest, and I populate every little cave with beings.

Meanwhile, the wind. It’s a constant presence, tearing over the arid plain, giving a low, unrelenting whistle to everything. One day I’m walking along the road at the edge of our enclave, minty eucalyptus on my right and broad, exposed plain to my left. This road is where that San Gorgonio wind blasts through, and as I’m walking a particularly strong gust comes up from the east. For reasons unknown – because of instinct or chance – I start to run with it.

I begin with a jog, then break into a sprint. The wind pushes me along, my slender body a sail, the trees a blur. I’ve never moved this fast before. I’ve never seen anyone else move this fast before. I am moving faster than the wind, a little out of control but mostly just amazed – and then something strange happens: I discover my kick. I can reach for another gear and go even faster. Nothing is ever the same.

Years pass. Mail from my father sustains me. He misses me, he loves me. He sends a photo of himself in uniform. As far as I’m concerned, he is defeating the Axis forces single-handedly. And then, one morning in fourth grade, my world flips back over.

“Russell Ellis,” my teacher announces, glancing toward the back of the room, “your father is here.”

My father and I move back to the city, and that speed of mine only grows. Gradually I learn to harness it to channel that magic kick. It gives my life direction. Coaches notice me. Local papers notice me. In high school I run the second fastest half mile in California. It’s a heady time. The world is smitten with track and field, hunched over their radios and sports sections. Mal Whitfield, Glenn Cunningham, Mel Patton: These are household names. When Roger Bannister shatters the four-minute mile in 1954, Edison might as well have invented the lightbulb all over again.

Me, I’m making my way up a ladder. My speed wins me a full scholarship to UCLA, and with that comes more notice – comments from professors, attention from my fellow students. For a brief period my magic kick and I are featured regularly in the Daily Bruin. It’s not altogether healthy to have one’s ego feted like this at such a formative age – but it’s fun. My sophomore year I return home to compete in the legendary Compton Invitational, notching my best time ever. For a period I’m officially the fastest quarter-miler in the world. But I’m gunning for something far bigger.

June 30, 1956 is a bright and smoky day in Los Angeles, or so I’ll piece together later. From the moment I wake up, I am so focused I can only dimly register my surroundings. I have one job: get to the Los Angeles Memorial Coliseum.

For years, my life has been a vector, pointed directly at an event born 2,700 years earlier. For an athlete like myself, there is no greater achievement than the Olympics, no higher honor, no clearer test of one’s worth.

How do you get into the Olympics? You show up at the Coliseum, this glorious white art moderne monument to competition, and you run faster than the other guys. Not all of them. Eight of us have made it to the 400-meter dash trials finals, and to advance to the Olympics, I just need to be in the top four.

I arrive at the Coliseum, and head into the low, windowless locker room to put on my blue and gold UCLA shorts and shirt. Then I step outside into a roar. I’m used to crowds by now, but I’ve never seen anything like this. The stands are jammed with men, women and children in bright clothing, shouting and waving their official programs. My father is up there with my stepmother. Amazingly, some of these people have come to see me, this kid from a windy farm who made good.

GUNATILLAKE: Let’s hang here for a little bit and enjoy the energy of the crowd. Russ’s hope and pride being expressed in how he is carrying his body. Chest open.

ELLIS: I am assigned lane four, and make my way to the starting blocks. Fingers. I always pay extra attention to the placement of my thumb and index finger on the gritty surface of the track, split at just the right angle, my left knee jutted forward under my chest, right leg stretched back: a coiled spring.

Runners take your marks. The roar in the stands draws to a tense hush. Get set. Every track I’ve ever circled has led to this one. BANG. A thin shot, and I’m gone.

My legs are thunder, my feet lightning, everything else blackness. My mind empties of everything but the lane before me.

Number four is decent – a gentler angle to manage, which means less energy needed to fight the turn. It also means you can’t see who’s behind you. How you parcel out your energy and speed and timing is up to you – until the final seconds, it’s a run not a race.

I come off the last turn and the stagger of the curve resolves itself. There are four runners ahead of me. Time to reach for my kick. I go down to find it as I have so many times, as I learned back on the farm. But it’s not there. Nothing is there. Or maybe the other guys have kicks, too. The finish line approaches. My legs are about to split from my body. I give it everything, and then, like that, it’s over. Fifth place. Run as fast as I’d hoped, and I’d be going to the Olympics, but I don’t, and I’m not.

In a fog I descend into the locker room, change, and, for the next 56 years, in the woods of Long Island and the flats of Berkeley, in the clamor of family and the halls of academia, but never again on a hot track aching for a gold medal, I live my life.

Mine’s a good one, as lives go. I go on to earn my doctorate in sociology at UCLA. I’d always been a natural sociologist – being Black in that era, my antenna was always up. After UCLA I become the first full-time African-American professor at the Claremont Colleges, in Southern California. From there I become part of the founding of SUNY Old Westbury, in New York. I begin teaching once a week at Yale. And then, when a new position opens up at UC Berkeley, I pounce, becoming the first sociology professor within the vaunted Department of Architecture in 1970. How do people interact with their environments, and vice versa? I love the research, I love teaching, I love my colleagues, and when I’m made a Vice Chancellor, I love that too, as much as you can love such a thing.

I love the woman who becomes my wife, and when we become parents, I love my son and my daughter more than I knew possible. Youth may be searing, but the lessons that come later are the profound ones: How to be a parent. How to be a partner. How to work through conflict, plan together. And then, one day in Berkeley, I learn something else: I’m a failure.

I’m tending the elephant garlic in my large, sun-splashed garden when the realization hits. The sensation is profound, almost mystical – I can only liken its intensity to the birth of my first child, when I felt a sudden gush of light, in the form of water, amidst a vast ocean, flooding me, pushing me toward some distant shore. Now, in a different way, I’m flooded all over – this time with the specific sensation of not having utilized my body’s potential. I was born a gazelle, but I didn’t live the life of a gazelle.

Outwardly I am a success, a working class kid with a turbulent childhood who carved a path to a loving family and professional acclaim. But inside I’m haunted. I could’ve done something, and I didn’t. My failure at the Coliseum is a tattoo on my forehead that only I can see.

GUNATILLAKE: This is a very different energy to what Russ was expressing when at the Coliseum itself. Can you see him? Tense, contracted. Do you know what it is to carry an old burden or regrets, invisible to the rest of the world but so tangible to us? If you do, what does it feel like? And let’s see if we can hold it a little bit lighter: softening and opening your body.

ELLIS: To the outside world this is baffling. One day in my 30s I’m in my office at Berkeley, a grand, book-strewn room shaded by the boughs of a delicate eucalyptus outside the window. There’s a knock on the door, and a colleague pops in. We get to chatting, and the subject of my Olympic disappointment comes up, not for the first time. A brusque fellow, my colleague looks me right in the eyes:

“Why the fuck don’t you grow up?” he asks. “You’ve got kids and a wife and a house and a job – maybe you can spend some time on what’s important now?”

He’s right. But he also can’t comprehend that kind of disappointment. I’m from a world of Jackie Robinson and Kenny Washington and Joe Louis, who raise the whole race by their accomplishments. My father worked at the post office, and he was king when I won those races. “Hey Russ, your boy Russ Jr. killed them!” In the Black community, athletic achievement was a thing that you could share with everybody else who was Black.

So it is that a single day – not even a day, less than a second – comes to loom over the thousands of days that followed, days that by rights should eclipse everything.

My failure at the Coliseum becomes the defining feature of my otherwise happy being. The wound threads itself into the fabric of our family. Dad didn’t make it to the Olympics, and that’s very sad.

Ironically, I counsel bereft students about this very fallacy all the time at Berkeley. Getting a “B” instead of an “A” isn’t who you are, I tell them, it’s just something that happened. An event. But my wisdom only flows outward.

The world turns. After a wonderful career at Berkeley, I take an early retirement. In my 60s I reinvent myself once more, taking up stone carving, then bronze work, and metal. I move on to painting, and have several shows. I’m a grandfather now, all new levels of joy. Maybe it’s the joy that causes me, at the age of 85, to start recording original songs. My kids, both musicians, help me. I call my first album Songs From the Garden. You know how you get a song in your head sometimes? I now get whole orchestrated movements.

One afternoon recently, because of my age or perhaps the quietude that Covid has brought, I find myself in a looking-back mode. You know, taking stock. What did I just do? What was that?

And that race – why did it have such staying power? The answer to this last one? Partly timing. I was still in the oven when it happened, still forming – those experiences stick.

But at a deeper level, I suspect I’d stumbled upon a tangible embodiment of an often intangible feeling: What might’ve been?

Aren’t we all plagued by that at some point? What might’ve been. The question isn’t abstract or amorphous in my case – it’s disturbingly quantifiable. That’s what a race is: a quantifiable fork in the road. Run a little faster and my life, the full trajectory of my existence, would’ve been different.

But of course the trouble with what might’ve been is that it blinds you to what is. That day at the Coliseum was a loss, that much is true. But what if it was a gift as well?

When I stopped gunning single-mindedly for the Olympics, all those years back, I slipped, chastened, into a life of peregrination. I wandered the landscape, finding joy here and there, never biting down hard on any one thing. A professor, an administrator, an artist, a singer, a partner, a father. For so long I thought this peregrination was my great penance. Now, replaying the footage, yet another dry summer giving way to another smoky fall, I see it in a new light. It is my great life.

Rohan’s closing meditation

GUNATILLAKE: We all have them, those sliding doors moments. Those forks in our lives which make us – like Russ – wonder what might have been.

If it feels safe to do so, bring to mind one of your own. Maybe it’s already come up for you as you listened to the story? Let’s see, what is it for me? Oh yes, as a 28/29 year old I had the opportunity to do the cliche meditation thing and to disappear into the forest for a few years. But instead circumstances led me to staying in the city and following the less well trodden urban mindfulness route. It doesn’t perhaps haunt me in the same way Russ’s moment did, but the thought of what might have been is here. I can feel it even today.

Gently, always gently, invite the memory and the thoughts that swirl around it here. Notice the movement of the mind. Feel into what this is like for you.

As a young meditator, I did a lot of striving. Sometimes it’s called efforting, which is a good visceral way of describing the energy I was putting into my practice. Working so hard to achieve. The idea of meditation being goal-oriented might sound odd to some of you. There’s a more popular cultural idea of meditation being super chill, and hey, let’s just go with the flow. But in traditional meditation there is absolutely a culture of achievement and attainment. There are totally the equivalent of Olympics qualifying times. And I know what the hurt of missing out feels like.

Ok. There’s a thing called negativity bias in the brain which basically means that if there is something that is not so great for us to fixate on, we’ll do absolutely that to the exclusion of things which are actually alright. You might know this tune. We finish the day, and the only thing we can think about is the bit that sucked.

So it does take work to move the mind away from the natural orbit of the negativity, to break its gravity – whether we’re talking about something small or something truly significant. But it can be a simple thing to do and the mindfulness hack for it is to prioritize the positive. Or what I like to call: look for joy.

Take your time. There will be something in your experience right now that is actually quite nice. The touch of the air on your skin. The warmth of your clothes on your body. Have a look.

It might not be something fancy. It might not be blissful sensations coursing through your chakras and what not. But it’s ok. It could just be the absence of toothache. It could just be calm. It could just be the smile that comes with your favorite memory from Russ’ story.

It’s a training. And for me, now many years later, if there is something worth efforting for, it’s the ability to drop into the lovely on demand. So valuable. So nourishing.

Less than a second. A splinter of time that became a mountain for Russ. A short time, but also a long one. Part of me is sad that he held it so tightly.

But I also know that the energy of that failure sparked the wider generosity, creativity, and impact of his life.

So thank you, Russ.

And you. You stay safe and well, ok?